The Weekly Howl

The British government just did something I agree with, and it feels almost gross to mention it. Also: who invented the week? And some Beeching-themed maps.

Forgive me, but I’m not going to major on the British government’s proposed asylum reforms this week. Yes, it feels like the biggest political story of the moment; yes, I too am disgusted by the talk of taking asylum seekers’ – refugees! – valuables off them at the border to pay for the privilege of being held in crumbling hotels or camps, and then not allowed to apply for settled status for 20 years. But I’ve written often about such things of late, my feelings haven’t changed, and there are only so many times I can go “This is awful and the people behind it inspire my disgust” before we all get bored.

Instead, let’s talk about this field.

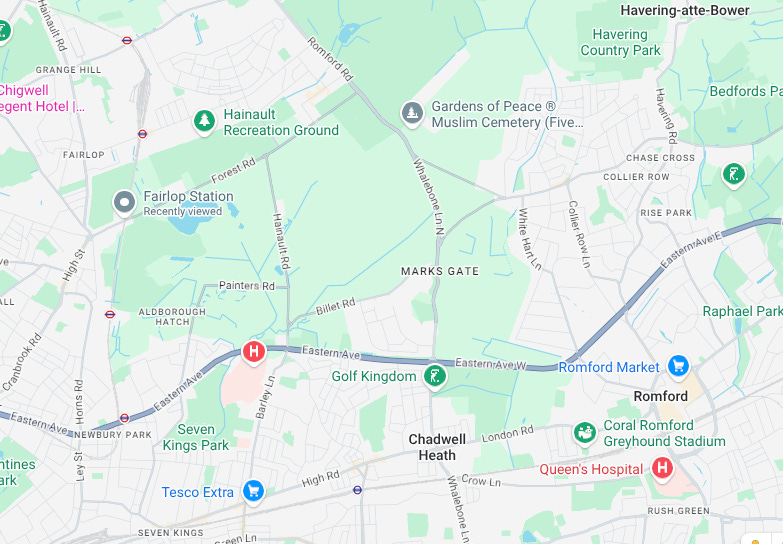

This green blur is not, you’ll be shocked to learn, the rolling parkland of the English countryside. In fact, the picture was taken from the windows of a moving Central Line train, which is why it’s all a bit blurred. What you’re looking at here is a surprisingly big stretch of Zone 4 – for non-Londoners, that means suburban but not that suburban; areas perhaps seven to 10 miles out – which lies directly adjacent to a tube line served by between eight and 10 trains to central London every waking hour. This is a level of connectivity that even huge chunks of the capital would kill for.

And yet, the local landscape looks like this:

A few bits of the area marked in green here are nice: we should probably keep those. Much of it, however, is not, and a place with such envious transport links surrounded by urban sprawl on three and a half sides seems, to me, an ideal place to build to help meet the capital’s pressing need for housing. And yet, it remains empty, without being in any real sense rural. The reason we’ve never built there is not because it’s industrially contaminated or prone to flooding or even particularly pretty. It’s simply that it’s green belt. We don’t build there because we never have.

The reason I mention all that is because of Tuesday’s announcement by Steve Reed. Proposals for new homes within walking distance of new “well-connected train stations” that meet certain conditions will henceforth get a default yes from the planning system, the housing secretary said. What’s more:

“...these rules will extend to land within the Green Belt, continuing efforts to ensure that a designation designed in the middle of the last century is updated to work today.”

What the conditions are we don’t yet know. There are some vague noises about “density”. How “well-connected stations” are defined is not currently clear, either, although the press release mentions trams as well as trains so we can probably assume you don’t have to be a mainline terminal to qualify. These details will matter.

But broadly, I’m pro. It is mad that a land use policy set generations ago should still determine where we build. And if we are going to nibble at corners of the green belt, the bits next to stations – where building will produce less traffic, and where you can be pretty sure you aren’t ruining actual, genuine countryside – is exactly where we should build.

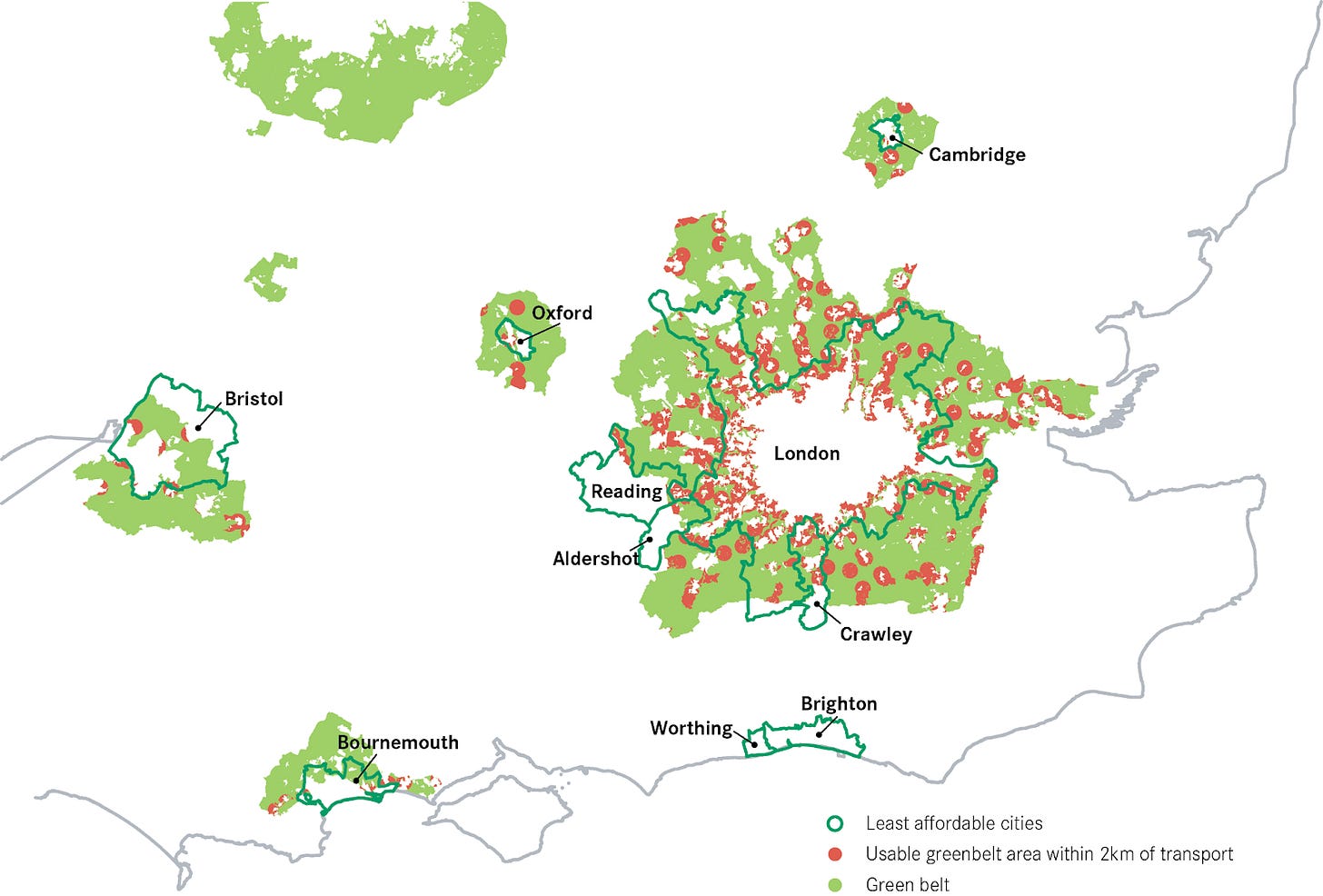

If we did, after all, we could build a lot of homes. In 2019, the Centre for Cities calculated that building at low suburban densities on just 60% of the bits of green belt within 2km of a station would provide space for 1.4m homes within the London area1 while leaving 95% of said green belt untouched. Include the capital’s entire green belt and that number is 3.4m. It’s big.

They even made a map. Look how much land is available – and how much green would still surround it!

That doesn’t mean building everywhere, the Centre noted: “Clearly, many of these sites will serve important local roles and so development should not happen on a blanket basis.” But it would be transformational, while leaving vast amounts of actual green space (95%!) available to enjoy.

It would mean more people could benefit from those frequent Central Line services. It is exactly what I hoped this Labour government might do.

And I almost missed it, because they instead won’t shut up about being horrible to foreigners.

Look, I know this is a slightly dry technical matter, not the sort of thing that excites the people clicking, or, more damningly, far too much of the media. And at this point, frankly, I feel slightly weird – dirty! – writing something going, “Hey, actually, this government just did something good.” The potentially transformative Renters’ Rights Act disappeared in the same way.

And this, surely, is another problem with the current focus on ever more abhorrent measures aimed at migrants. It means genuinely good measures go unnoticed – and those who might have felt minded to speak up about them no longer want to, in case someone thinks they’re okay with rest.

I’m not saying it’s the worst thing about trying to out Farage Farage. But quite apart from the moral abhorrence of this strategy, it is also quite absurdly moronic.

The Christmas Market is open

Last week at a fashionable media party™, someone introduced me to their dad, for whom she’d bought a copy of A History of the World in 47 Borders and got me to sign it. I enjoyed that. You should feel free to introduce me to your dad, too.

Anyway: if a dad YOU know would like a signed book this Christmas, then the lovely people at Balham’s finest book boutique Backstory have your back. Excellent presents for non-dads, too!

You can order Borders here or the Compendium here, and I will – as both the person who asked me to write a veritable essay for her sister, and the one who invited me to call his friend “a real piece of sh*t”, can both attest – write anything you want. Really, I’m very accommodating.

Imaginary Time

Pop quiz, hotshot, here’s a game of spot the odd one out: day, week, month, year. One of these things is not like the other. But which? But which?

The answer – which you’ll obviously know if you read either the summary at the top of the email or the social media promo, because I in no way thought this through – is the week. The other three are all, to a greater or lesser extent, astronomical units of time (a single rotation of the Earth; the lunar cycle2, the period between new moons; the time it takes the Earth to complete one journey around the sun). They are things that exist, irrespective of our awareness of them, and were out there waiting for us to discover them.

The week, though, has no such independent existence. It’s an entirely human construct, which could be – indeed, often was – of an entirely different length. It’s an illusion.

And yet, it’s an illusion which is shared by, essentially, the entire human race, which we use to regulate our lives and to which we grant enormous power. A large chunk of humanity observes the Sabbath, or some equivalent thereof; even those who don’t either observe, or complain of the absence of, its secular spin-off, the weekend. What’s more, we imbue the days of the week with personality, separate enough from our own experience of them to serve as cultural reference points. Every day is like Sunday. Garfield hates Mondays. TGIF, amirite?

So how did we all buy into this nonsense, exactly?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.