Something which paying subscribers got to read in April. Experiencing an all-consuming sense of regret you weren’t among them? Well:

The Great Crash (October 1929). A long bull market (rising values; as opposed to a bear market, falling ones) had seen loads of retail investors (the public) pouring money into stocks and shares in the belief they’d be able to sell them at a profit. Worse, many people – worried about being left behind – had borrowed money to do it.

That meant that, when the market showed the first tremors of a correction on 18 October, a load of people panicked and sold, causing prices to slide further. On Black Thursday (24 October), this worry turned to panic, a record number of shares were traded in New York, and the market dropped by 11%. It fell another 13% on the Monday, and 11% the day after that.

It took another three years for the market to hit bottom, having lost 90% of its value. By then they were calling it the Great Depression. Accidents will happen.

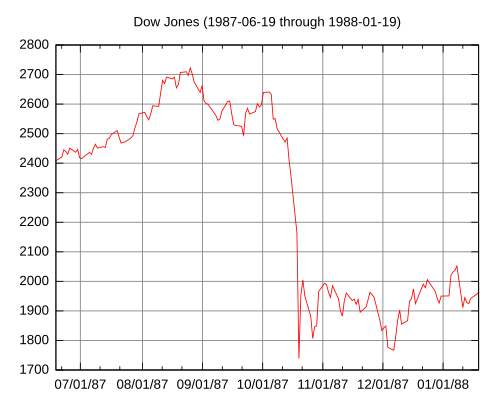

Black Monday (19 October 1987). After five years of the world’s global financial markets acting like a cross between a Jilly Cooper hero and Del Boy, it suddenly all went wrong: the Dow Jones index fell 22% in a single day. That’s still the worst ever single day in trading history, which is why everyone keeps going on about it.

There are other ways, though, in which this one… wasn’t actually that bad?

For one thing, it seemed to have been caused partly by early computer-based trading models, which have a nasty tendency to cause feedback loops. (”Things are losing value! Better sell them. Oh! Things are still losing money! Better se-”) To stop that happening again, it led to the introduction of circuit breakers – pauses in trading for short periods, or the rest of the day, to prevent crashes based not on real things but on self-perpetuating panic.

More to the point, as bad as the crash was, in most countries it wasn’t followed by a recession. The US Federal Reserve and other central banks stopped in to provide liquidity, to make sure people weren’t defaulting because of short term debts, and thus restore market confidence. One exception was the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, which decided the real risk was inflation and refused to loosen monetary policy, thus turning the crash into a four month crisis in which the market lost 60% of its value and triggering a contraction in the real economy. Well done there.

(The 2008 financial crisis, incidentally, featured no single day as bad as Black Monday – the worst was a 9% fall on 9 October – but during the full 17-month bear market, from October 2007 to March 2009, the S&P 500 lost around half its value. Oopsie.)

The 2022 Russian stock market crash. In late February 2022, Vladimir Putin announced that Russia had recognised the breakaway Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic as independent states. Since it was Russia-backed paramilitaries that had been pushing them to breakaway, this should have surprised nobody.

It did, however, seem to surprise the financial markets: that day, the local stock market MOEX fell by more than 10%. Two days later, it fell by a third. After that the country’s central bank closed the markets for a month, in the hope prices would recover. They didn’t.

In all, the market had fallen by half since its high the previous autumn. It’s almost like invading a neighbour and making yourself a pariah state might be in some way bad for business.

The Dot-Com Boom, later known as the Dot-Com Bubble (1999-2002). If other crashes are notable mainly for their depths of the trough, this one is striking instead for the hysteria that preceded it. Equity markets began climbing steadily from 1995, accelerated through 1999 thanks to low interest rates and generous venture capital investments in exciting new businesses “On-line”, then went stratospheric in 2000. Across that period, some indexes rose by 800%.

Then, in March 2000, they began to slide, a trend accelerated the following year after 9/11. Eventually, they would fall by 78%, wiping out essentially all their gains. These were at least investments in actual companies – but still, how anyone lived through that and retained their belief in the rationality of markets, I’m not entirely sure.

The 2020 stock market crash. Okay, this one was kind of rational: the global pandemic, and a response that meant that many people in many countries couldn’t go to work and no one could spend any money, was always likely to put a bit of a damper on the real economy.

At any rate, markets fell by 30% and years of gains were wiped out in under a month. March 2020 includes a trio of dates known as “Black Monday”, “Black Thursday”, and “Black Monday II”. That “II” is not a good sign.

The Dutch Tulip Bubble (1634-7). The original and still the funniest. The result of two broadly positive developments – the invention of futures markets, and the import of a lovely type of flowers – combining into one catastrophically stupid one.

In its golden age of the early 17th century, the Dutch Republic was one of the richest countries in the world, with one of the most sophisticated financial markets to boot. One of the innovations invented in that period was forward markets, in which you could trade contracts to buy a product that didn’t exist yet. (Such things are useful for creating price certainty, hedging against risk, and so on.)

Futures contracts were particularly useful for the trade in tulips, first imported from Turkey just a few decades earlier, because they can only be moved for a few months over the summer and bloom for roughly a week. These were expensive, luxury items – as early as 1610, a single bulb of a new type of tulip was worth enough to be a plausible wedding dowry – and from 1633, decades of rising prices tempted many regular Dutch investors into a previously specialist market, sometimes mortgaging everything they owned to buy their way in and make sure they didn’t miss out.

It’s not that people exactly believed these tulip bulbs were worth all that money, you understand: they just thought other people would believe that in future, an example of a phenomenon known as the “greater fool theory”. The problem is, one day in February 1637, they suddenly didn’t. Prices fell – and then, because they’d only been so high because everyone thought they’d get higher, they just kept falling. People were ruined. What to do about enforcing those futures contracts became a national political issue.

For a long time this has been remembered as the strangest and infamous market crash. Whether it is quite as stupid as crashing the global stock market as a precursor to taking down the entire global economy, just because you are for some reason unable to understand the difference between “selling a product to” and “stealing money from”, remains to be seen.

One of the lessons we can take from all this – look, I'm not saying it’s a banger – is that markets very rarely plateau. They’re either climbing or falling; growing or shrinking. That’s something they have in common with the Roman Empire, the universe in certain branches of cosmological theory, and also newsletters like this, which need a regular flow of new subscribers just to stand still

As ever, if you want to read the full thing but can't afford it, just reply and ask nicely I'll say yes, I always do. But if you can afford it: