A new way of thinking about history

In search of lost time.

Sometimes I think of a topic, go off and research it and then write an essay, or at least one of those sort of “listicles but for people who like Only Connect” things I specialise in. On other occasions, I just have a half baked idea I want to get down, without knowing quite where it’s going or whether it’s worth anything. This, I’ll admit now, and which you may have already gleaned from this intro, is one of the latter. It might be insane, but I hope it sparks thought.

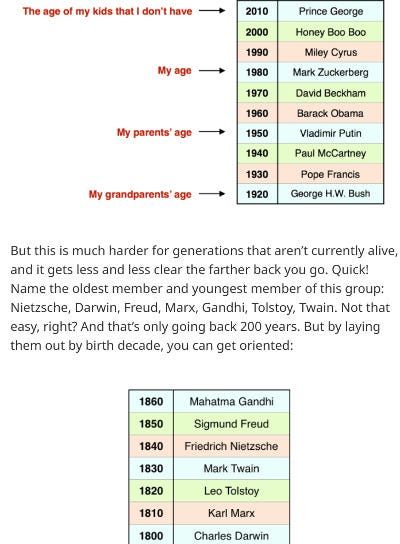

There’s a 2016 Wait But Why post, called Horizontal History, which I think about a lot. In it, Tim Urban proposed a new way of thinking about the past to help us understand it: translating raw dates into generations, to make it easier to grasp that Fredich Nietzssche, say, was doing his thing approximately 30 years after Karl Marx was doing his.

This is a great idea, which I think is worth investigating more, but unfortunately someone else has already had it, and you should go read his post. (Preferably not yet, though.) It is, though, the best way of explaining and justifying my own, similar proposal.

It’s easy enough to say that “X happened Y years before Z”, and to grasp, in the sense that we’ve all understood numbers since infant school, what that means. But that isn’t visceral: knowing something isn’t the same as feeling it in your gut, and that, I’d warrant, is how we experience recent history. If I hear that something happened in the 1970s, say, even though it’s before my time, I can immediately orientate myself with both what else was happening at the time and with how it relates to the timing of things that happened before and since.

The first of those things is not something we’re going to be able to replicate at any other point in history – I’m not sure even historians grasp the decades of previous centuries in quite the way they do those of the 20th and 21st. But the relative orientation thing, I think, might be something we can fake with other time periods by means of direct comparison.

Imagine it’s 1815: one of the most interesting periods in western political history is reaching its conclusion, everyone is presumably knackered. It’s one thing to understand there have been 20 years of European War, following revolutions in France and before that America. But what did that feel like?

To help grasp that, let’s simply change the dates: imagine that the calendar at the time of Battle of Waterloo said it was 2023, and move everything else up by 208 years, too. Here’s what you get.

Leaving aside that this helps make my case for this era as boxset material for some streaming service, it also makes it easier to grasp, I think, quite how busy and chaotic this period must have felt for those who lived through it – how the Napoleonic Wars had been going on, effectively, forever; how the idealism of the American revolution hung over the French one; how the Seven Years War had hung over the American revolution in turn. (It also, amusingly, reframes George Washington as a sort of Tony Blair figure, but perhaps we’re at the limit of usefulness here.)

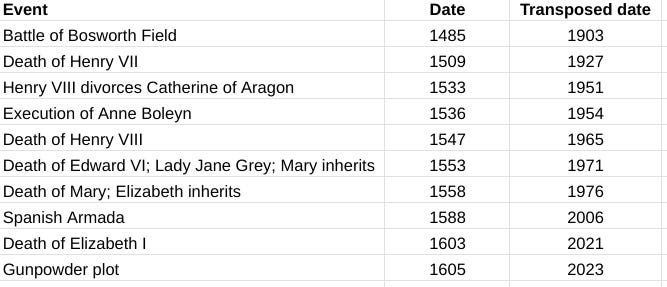

Le’ts try again with another period. This time, let’s say our base year was 1605, that of the Gunpowder plot:

If I’m honest I’m not sure this is as illuminating. But it does highlight quite how much of his reign Henry VIII was married to Catherine of Aragon for, and how new and thus rickety the Tudor dynasty was, which is quite useful for understanding a lot of what happened in the 1530s. Also, this is a personal malfunction, but I hear 1588 and imagine the Armada taking place at the end of the Elizabethan era – reframing it to a date farther in the past than the crash and the iPhone are now makes clear quite how much could have happened afterwards.

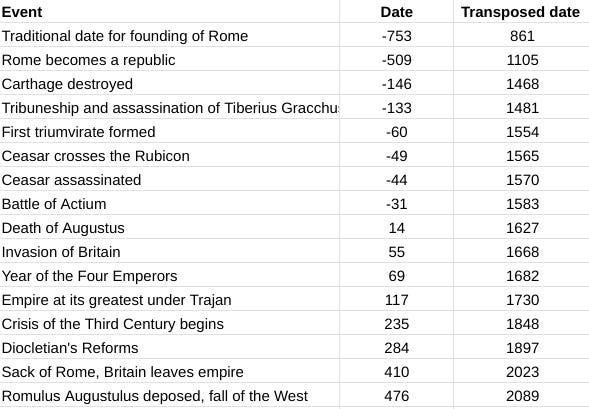

One last attempt. This time, it’s 410, the year, roughly, that Britannia falls out of the Roman Empire:

Reframing it like this really brings home both quite how venerable Roman civilisation was by the 5th century, and quite how long Britain had been in the empire: Brexit was traumatic enough, but imagine the end of a union that had held since the 17th century. In the same way, both the length of the 3rd century crisis, and the period of relative stability that followed it, both look a lot longer framed like this than they’ve ever felt to me when the dates attached to them are in low three figures. This too may be my own malfunction but I’ve sometimes conceived of that period as a last gasp, a description that’d look stupid when applied to an order that had held sway since 1897.

There are some problems with this approach. One, I’ve increasingly feared as it’s gone on, is that it’s obviously mad and I shouldn’t have written it down. Fair enough. Another lies in interpretation. Different dates mean different things to all of us: to me the ‘90s feel, not recent, exactly, but not historic. Those ten or twenty years younger than me I suspect have a different view of them, by virtue of the fact they didn’t spend the years of the Blair ascendancy trying to get served in pubs.

Another issue is that I’m not sure we actually perceive time in an entirely linear fashion. I still on some level imagine that the ‘60s was a generation ago, the war two generations, because that’s what they were when I was growing up. These things tend to lodge. More than that, the meaning of those things in my head, as a social revolution and national trauma, remains fixed no matter how long ago they were. Transposing dates like this risks wrongly carrying those meanings over.

All that said, though, this does give us a frame of reference for understanding how long ago events took place that isn’t rooted in simple maths – a way, like Urban’s horizontal history, of conceptualising the relative layers of the past, so that events weren’t “X years earlier than Y” but in the equivalent of your parents’ or grandparents’ time. It allows us to feel it.

Or, maybe, I’ve just gone mad.

The Gratuitous Dog Picture & Sales Pitch Bit

The article above is an extract from the archive of the Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything, a weekly newsletter which goes out every Wednesday at 4pm. Become a paying subscriber, and each week you’ll get a bit on politics, some diverting links, an article on history/geography/language/something, and the map of the week. But that’s not all! You’ll also get a warm glow of satisfaction that you’re helping me to write fun and interesting things, not nasty corporate ones. And all for just £4 a month or £40£28 a year! Ah, go on, go on, go on.

But: we’re all broke right now. If you can’t currently justify paying for some nerd’s substack (unemployed, underemployed, impoverished student, and so forth), just hit reply and ask nicely and I’ll give you a complimentary subscription, no questions asked.

Alternatively, why not pre-order my new book, out next April? Go on, it’ll make your life better.

I do like this way of thinking about history (and Horizontal History). I think you're right that we don't experience time in a linear fashion as we don't naturally experience numbers in a linear fashion: children think of numbers logarithmically (sort of) until they are taught the number line, and even as adults we start to get a bit non-linear about billions, trillions and other non-countables.

I'm also interested in History in the Present Tense, what would it have been like to live through it, day by day, as we do live through our current times. Take out time dilation, the benefit of hindsight, and especially of luck and stuff just happening, and what would it have been like after the Great Stink unlocked the money and they started digging up all the roads again, they've only just built a railway, Chelsea Bridge delayed *again* and anyway, you don't believe all that "it's shit in the water" crap do you?