Elections, Elections Everywhere

This week, it’s a politics special. Ottawa! Canberra! Runcorn!

So, with the spring election season in full swing, let’s check in on the state of play. In Canada (don’t worry, I’m not going to dwell) the result of Monday’s contest was somehow both the thrilling blow out we’d all been waiting for, and also oddly underwhelming. Yes, the Liberals won a fourth term that seemed inconceivable when the year began, and did it so convincingly that the networks called the result not long after 10pm Ottawa time. Yes, Conservative leader Pierre Pollievre lost his own seat.

At the same time, though, the Liberals didn’t actually get a majority (with 169 seats, they were three short). And for all the talk of Donald Trump having fuelled a Liberal surge, the Tories gained 24 seats, and were not far off their polling at the turn of the year (41.3%, to the Liberals’ 43.7%). The outcome suggests Liberal consolidation of the left-leaning vote, as opposed to either a moment of national unity or full-on Tory collapse. A good result, sure; but hardly 1993.

It will, however, be a far happier outcome from a left-leaning point of view than we can expect from tomorrow’s English local elections. The last time this particular set of seats were up was 2021, when the rally-round-the-flag effect met the vaccine bounce to help Boris Johnson’s Conservative party win a whole bunch of councils where they’d normally have no chance. Even if they’d made the slightest effort to account for the mistakes of their 14 years in government, which they haven’t, the Tories would thus be on course to struggle; as things stand they’re facing wipe out, losing perhaps 500 councillors on a good night, 700 on a bad.

The main beneficiary, though, is unlikely to be an unpopular Labour party already struggling in government. (The experts have them holding roughly steady. Based on no expertise whatsoever, that to me feels optimistic.) The Greens will pick up a few; the LibDems a few dozen. The big winners, though, will be Nigel Farage’s Reform, who could win anywhere from 350 to 700 seats. The party is also favourite to win mayoralties in Lincolnshire; East Yorkshire; possibly even, if we truly are in the worst timeline, the West of England. (Greater Bristol!) They’re favourites in the Runcorn by-election, called after Labour MP Mike Amesbury punched a constituent and resigned, too.

Not every party that’s cosied up to Donald Trump is having the same week.

All this has meant a certain amount of hysteria about the possibility that Farage could be on course for real power. The government, opposition and Reform are all polling at 20-25%, and if that held true at a general election then an electoral system designed for a two-party contest might start spitting out some genuinely weird results. Farage is 3 to 1 to be the next prime minister. The Economist has christened him “The man Britain can’t ignore”. It all goes some way to explain why both Labour and Tories are falling over themselves to appeal to potential Reform voters, in apparently blissful ignorance that voters lost to the LibDems, say, actually also count.

I don’t want to be too dismissive of all this. Terrible things do happen; Farage has got a lot further than anyone, probably including him, would once have expected. Nonetheless, some comforting words of caution. The next election could be more than four years away: so much could happen by then, up to and including “war with Russia”, that all predictions made now are functionally meaningless.

Reform with power might also turn out to be self-limiting. If, as seems likely, the party does win a mayoralty or two tomorrow, then that’ll mean some Reform politicians with their own mandates. History would suggest that Farage will not respond well to that: the clever money must be on the possibility that he’ll try to order them about like underlings, then brief against and throw them out of the party if they fight back. All that’s without even considering the fact that Reform might also – inconceivable I know – turn out to be bad at running stuff.

Most importantly though, the hysteria about unstoppable Faragist momentum abroad in the media ignores the fact that people vote to stop things, too. Labour won big last year because people wanted the Tories out. Mark Carney won this week because enough people on the left of Canadian politics wanted to block a Tory leader that had made the mistake of being warm to Donald Trump. That isn’t happening in this week’s locals, because, well, they’re locals. But it is inconceivable that, were Nigel Farage really poised to become Prime Minister, there wouldn’t be a push back from the majority of voters who would rather die. That may not be enough to prevent it – but neither is it something reflected by any of the polls or MRPs currently doing the rounds.

We shouldn’t understate the risk here – but neither should we descend into hysteria. Four more years.

There’s another election looming too, of course. Australia is having a general election on Saturday, as it does approximately every third weekend. First, though:

Me and My Big Mouth

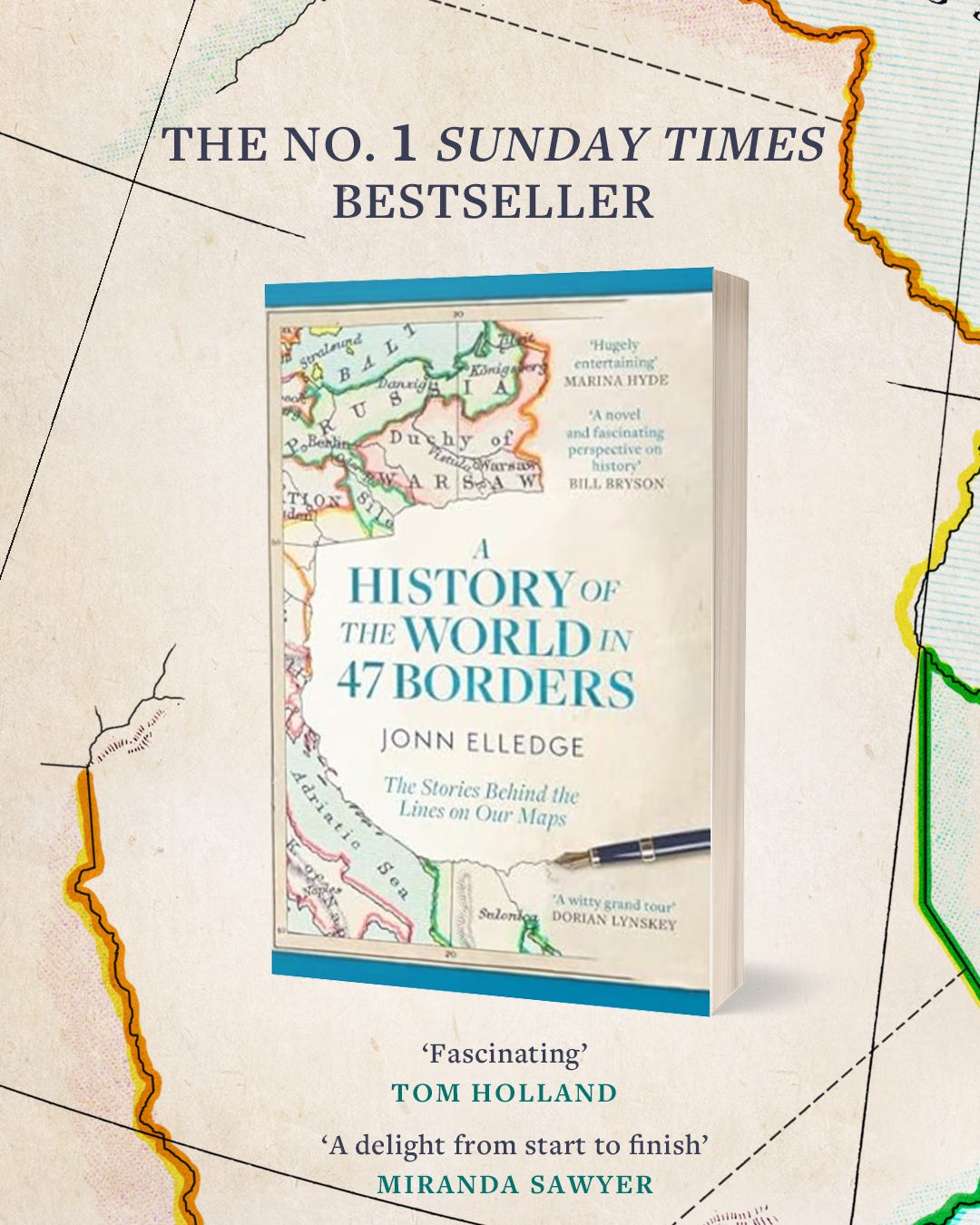

A reminder that, if you so wish, you can come see Dorian Lynskey and I chat borders and whatever else is on our mind at Foyles Charing Cross Road next Tuesday..

Right, self-indulgence done with, let’s get back to the content.

I Try To Understand the Australian Election

Two things seem to me to be true about AusPol, as it’s cheerily referred to on bits of the internet: Australia always seems to be having an election; Australia always seems to be changing its prime minister. This weekend, it will do at least one and quite possibly both of those things. It goes to the polls on Saturday.

I don’t really know that much about Australian politics. I do know it’s one of the few countries ever to literally lose a prime minister, the Liberals’ Harold Holt, who disappeared in 1967 thus sparking a conspiracy theory that he was a Chinese spy. (Actually, he almost certainly drowned.) Almost everything else I know about it comes from a delightful book, Ben Pobjie’s history of his own country, Error Australis, and the main thing I remember about that is that it has a chapter named The Menzies Centuries. (Robert Menzies was Prime Minister from 1939 to 1941, and again from 1949 to 1966. Imagine the same guy being PM on the eve of the Blitz, and when the Beatles were gearing up to record Revolver.)

Anyway, I like using you lot as an excuse to learn things, and I did Canada last week, so let’s try to make sense of this, shall we?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.