Exit, Pursued By A Bear Market

This week: can we not go just five minutes without another once-in-a-generation global economic meltdown *please*? Plus some noteworthy British monarch deaths; and Manchester gets a Tube Map, sort of.

The term “Awful April”, which some newspapers have been trying to popularise this week, is irritating in the extreme. Even if it didn’t feel unfair to blame the month itself for a confluence of economic crisis and public policy choices, which it does, “Awful April” isn’t a UK household spending squeeze, it’s a Roald Dahl character.

Nonetheless, the figures behind the label don’t make for pretty reading. The energy price cap is up by 6% because of geopolitical factors; water bills up by 26% because of poor regulation and money grabbing shareholders ones. Throw in higher tv licence, car tax and assorted other sundries, not to mention the welfare squeeze, and it isn’t very pretty.

As if that’s not enough to worry about, today is “Liberation Day”, on which Donald Trump is giving US citizens the freedom to not buy overseas products any more without incurring hefty tariffs. Exactly what those tariffs will look like – who they’ll hit; whether they’ll include, say, car parts as well as completed products, thus wrecking swathes of domestic industry, too – still remains, at time of writing, a matter of speculation. Who at this point would even guess.

But it’s more than plausible that Trump is firing the starting gun on another once in a generation sort of global economic crisis (the third, by my count, in two decades). What we really do not need right now is another crisis. At this point in history, I feel strongly that we should in fact have fewer crises.

I graduated from university in 2002; by the time I really started my career, rather than mucking around then doing a masters degree, it was 2004. These, though I didn’t know it then, were the good years. Friends in banking or law were making out like bandits; London was booming. Other places perhaps weren’t, and houses were a bit expensive but, well, that bubble would probably burst right? It always had before.

If someone had told me I had less than three years before the first tremors of a crash we’d yet to have bounced back from two decades later, and that the housing bubble wasn’t going to burst after all, I’d have made different choices. Found a way to buy property earlier. Grabbed for the money, and written one of those tell-all books about the crash. Generally acted like I knew it was the last days of Rome. But we had no idea these would be the only good times this country would see for decades. Even when the crash happened, I assumed it was a blip.

I am in my mid-40s, almost exactly halfway between my graduation and my retirement date (LOL, right). I have known precisely three years of sustained growth. I was a late starter, but to have known proper growth at all of the sort we took for granted for decades – centuries! – you’d need to have your 40th birthday in sight. Any younger than that, and you were probably still in education. That is twenty years of adults who’ve never known a “normal” economy.

There are reasons for this, I know. An ageing population. A lack of investment, both public and private, which I never stop banging on about. A slowdown in European growth (even more ageing populations!), and the shift in the centre of the global economy from Atlantic to Pacific.

But it is hard to escape the suspicion that one of the reasons for these lost decades is just this run of catastrophically bad luck, of poor policy choices either leading to or running headlong into crisis after crisis. Austerity, Brexit, Covid; more austerity, an inflationary crisis brought on by the war in Ukraine; now Trump and more austerity, still.

Again we are being told to tighten our belts. Again there are more reasons to think it’ll get worse than better. At least this time no one’s lying to us that, if we just do this one last heave, then the good times will surely roll. Perhaps this government’s miserablism is a form of mercy.

A tale of two books

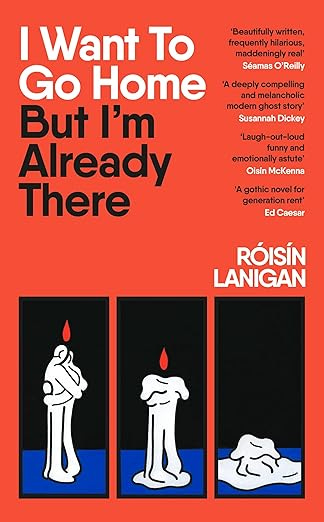

A book I am reading and very much enjoying right now, which you lot will almost certainly like: I Want to Go Home But I’m Already There, my friend Róisín Lanigan’s “gothic novel for generation rent”. I’m only halfway through, but so far it’s a brilliant and unnerving mixture, like the unholy offspring of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper and Rightmove. Róisín talks about the book in the Guardian here; you can and should buy it now.

Oh yeah also Waterstones chose some nonsense called A History of the World in 47 Borders as its non-fiction book for April. No biggie.

To promote it, by the way, they asked me to write about yet another border conflict: the Whisky War, between those two military behemoths, Denmark and Canada. You can read that here.

Some noteworthy British monarch deaths

“Oh you’re writing British are you?” I can feel angry messages already being typed from some distance to the north. “But I bet they won’t be ‘British’, will they. They’ll all be ‘English’.” You’ll just have to wait and see won’t you?

Edmund of East Anglia (c855-869): Also known as Edmund the Martyr, a sobriquet which may give an early indication where this particular story is going, and a man of whose existence we’re aware entirely from two things:

1) “numismatic evidence”, which is a posh way of saying “coins”, and

2) the rather flowery stories of his death fighting the Vikings, recorded in Asser’s Life of Alfred the Great and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

These were sexed up considerably by later texts until the tale ran that he didn’t meet the Vikings in battle at all, because that would be un-Christ like. Instead, he was captured, beaten, tied to a tree and whipped, then – after calling for the Lord’s help – shot with so many arrows that he looked like a hedgehog. What was left of him was then beheaded and his head tossed into the woods, where it was generously protected by a wolf until his kinsmen heard it crying out for them, so that they could reattach it to his miraculously unwounded body.

It is at least possible that this story is not entirely true. Anyway, that’s why there’s a town in Suffolk named Bury St Edmunds.

Constantine I of Scotland (862-877): Actually probably just king of the Picts (the idea of “Scotland” was probably not invented until the next century), and also not the first Constantine (another Causantín had reigned half a century earlier; early medieval regnal numbering is always a ballache). Anyway, also died fighting the Vikings. We don’t actually know much more. I’ve included him here for two reasons:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.