Guest post: A women’s history guided tour along London’s Suffragette line

Nuns, jiu-jitsu and the first women’s football match.

Hello everyone, Jonn here. What follows is one of those guest posts we occasionally like to throw at you, written not by me but by one of my mates. Isabelle Roughol is a journalist and public historian, who’s currently in the process of launching Broadly Speaking, a women's history podcast and newsletter. You can, and should, sign up to her mailing list here.

The following is something she’s written to coincide with the biggest change to London’s transport network in quite some time…

To go from being branded a terrorist organisation to getting one of London’s six Overground lines named after you is quite the historical trajectory. But as of this week, the suffragettes have given their name to the London Overground line from Gospel Oak to Barking, once known as the Goblin. In honour of the new signage finally being rolled out across London this week, please follow me on a women’s history tour along the Suffragette line.

But first, a refresher on that name. The people advocating for the expansion of the franchise were originally called suffragists. In the last years of the 19th century, Millicent Garrett Fawcett led the 50,000-strong National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies and believed firmly in non-violent campaigning. Surely, if they signed petitions, lobbied MPs and didn’t get too shrill, they’d get their way? Suffragists wore Green, White and Red, colours which not so obviously stood for Give Women Rights.

But after a few years of polite and futile campaigning, a number of women grew tired of the politics of respectability, and a movement that was decidedly upper-class. More radical and working-class activists formed the Women’s Social and Political Union around Emmeline Pankhurst and lived by one motto – “deeds not words”. Their colours were the now more famous Green, White and Violet – Give Women Votes.

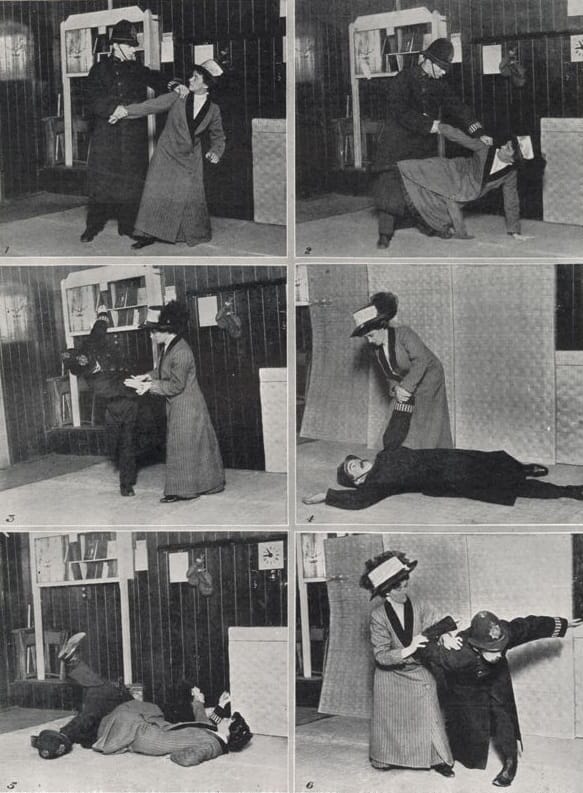

Pankhurst and her friends’ deeds consisted at first of heckling politicians, chaining themselves to buildings and slashing paintings in museums (there is nothing new under the sun). They culminated in arson attacks and bombing Lloyd George’s house. Sikh princess Sophia Duleep Singh threw herself in front of the prime minister’s car and survived; Emily Wilding Davison threw herself under the king’s horse and did not. Law enforcement’s response was brutal. Hunger-striking women were force-fed with rubber tubes or released only long enough to recover and be returned to prison. Police groped and beat protesters violently. Activists learned jiu-jitsu to defend themselves.

I’ll give you one guess as to which British newspaper would come up with a demeaning nickname for progressive women. According to the subhead of his obituary, which goes on to describe some vintage Fleet Street antics and hints at plenty of uncredited work from his wife behind the scenes, the term “suffragette” was first termed by the Daily Mail journalist Charles Eustache Hands.

A bit of linguistic pedantry because I happen to be French: “ette” is a suffix used to both feminise a noun (that’s the final “e”) and diminish its stature (“et”). Outside of a girl’s childhood nickname, it’s a diss. Nothing that ends in -ette can be remotely threatening. A maisonette isn’t quite a house, a kitchenette is a screw you from your landlord, and a suffragette is a little girl who should go home. Unfazed though, the radicals adopted their opponents’ insult as their new name, much like the impressionists and the guillotine had before them or Obamacare did closer to our own time. Women wore the name as a badge of honour. Suffragists want the vote, the women proclaimed, but suffragettes get it. (You’re not mad, the rhyme doesn’t work, it’s a terrible slogan.)

In a tale as old as social progress itself, suffragists and suffragettes clashed with one another over issues of ideological purity and how to win over public opinion. As the suffragettes’ tactics got increasingly radical, 50,000 women marched on London’s streets in 1913 to say “Not in our name!” Ultimately, both campaigns advanced the cause – but what really won it was the mobilisation of British women in fields and factories during World War I. One school of thought is that, after it, it became politically untenable to deny them the franchise. A more sobering interpretation is that the elite just didn’t want to give increasingly radical working class men freedoms which their “betters” – upper class women – did not also enjoy.

What does this all have to do with the Gospel Oak-Barking Overground line? Most of the suffragette organising was happening in among working-class women in the eastern suburbs of London. Let’s start there.

Barking Riverside

Let’s ignore that the suffragettes’ headquarters were actually in Bow, plenty of organising was happening in Barking. In particular, Transport for London has highlighted Annie Huggett, the longest-surviving suffragette, who grew up in Barking’s first council housing, where she’d have the Pankhursts over for tea. She lived to 103 years old, 93 of them in the borough, and is buried at the local Rippleside cemetery.

Before you get on the train though, walk down the pier, look to the east, and about a mile downriver, admire the Dagenham Ford Motor factory. On 7 June 1968, the women sewing car seat covers there walked out after learning their work would be regraded as unskilled, and that they would earn 15% less than men at the factory. Branding women’s skills as less technical is a classic method to frustrate their wages and segregate them from parts of the job market where they’d compete with men.

There is a long history of this, particularly since the introduction in Britain of the “breadwinner wage” model – the idea that a man’s work should support the family, while a woman’s income was just extra pocket money. The Ford Motor women’s three-week strike earned them a gradual wage increase, though it was only after another strike in 1984 that their work was finally regarded as skilled. But vitally, it was their meeting with Harold Wilson’s Secretary of State for Employment, Barbara Castle, that inspired the passage of the Equal Pay Act 1970, which prohibits the unequal treatment of men and women in the workplace.

Barking

Walk down the green past the Three Lamps, a traditional place of protest where suffragettes and strikers assembled, and you’ll hit Curfew Tower, the last remnant of one of the prime centres of female power in England. Barking Abbey was founded in 666 to convert East Saxons to Christianity. It was originally a “double monastery”, hosting both men and women – something which was not uncommon, but was always under the leadership of a woman.

Aside from a short interruption under the Danelaw, the abbey remained open until Henry VIII got involved. At the time of dissolution in 1539, Barking Abbey was the third wealthiest nunnery in England. Nuns were sent away with a £5 or £6 annual pension, roughly the living wage of a craftsman, as much as the average monk’s pension but twice as much as the average nun’s. The buildings were levelled and the stones reused within months.

The closing of religious houses was devastating to women and to female culture. Nunneries were the only respectable option outside marriage, and the only place women could live in community and nurture their spiritual and intellectual side. Former nuns had no right to marry, no craft and no role in the new Church of England. Some tried to maintain their communities by renting houses together. Most ended life in abject poverty. (I have researched this quite a bit and will write about it more, so sign up for my newsletter if this riles you up as much as it does me.)

Woodgrange Park

Jane Savoy was an ally of Sylvia Pankhurst. A poor East London brushmaker, she was part of the delegation of six women who met with Prime Minister Herbert Asquith in 1914. She showed him her work and, according to Pankhurst’s later recollection, told him:

“This is a brush I am making for twopence; it is sold wholesale for 10s. 6d. I work from eight in the morning till six at night making brushes and four hours at housework – fourteen hours a day. My hands get cut with the wire. I have worked at the trade 43 years. As I have to work so hard to support myself, I think it is very unfair that I cannot have a voice in making the laws I have to uphold. I think I ought to have a voice in electing our Member of Parliament.”

Jane Savoy died in January 1928, five months shy of the law that would mark her victory. She was buried in an unmarked grave at Woodgrange Park cemetery. She never voted.

Wanstead Park

You just crossed the Elizabeth line, named after Elizabeth II. The late queen can now claim two London rail links to her name (the Jubilee line opened for her silver jubilee), twice as many as her great great grandmother and the only naming category where she’s got Victoria beat. See below.

Leytonstone High Road

A well-known 19th century London institution was obliterated to build the tracks you’re travelling on at this point of the line: you just passed over the site of the Princess Louise Home and the National Society for the Protection of Young Girls.

The residential school was created to prevent poor and orphaned girls from being forced into prostitution. A girl would arrive, usually sponsored by a wealthy patron on the condition she was “very clean in her person, especially the head” and owned an umbrella. (What?!) She would receive an education in literacy and numeracy, sewing and laundry, and eventually be sent on her way into domestic service.

Nothing sinister here: by all accounts, it was a comparatively decent way to spend a poor childhood in Dickensian London.

Leyton Midland Road

Sorry, I got nothing. Locals, advise.

Walthamstow Queen’s Road

The queen with the road is, of course, Victoria. This is just one of an absurd number of places named after her, even beyond the Commonwealth. Victoria has hundreds of roads, streets and schools; 46 listed pubs; towns in Argentina, Romania or Kansas; a Tube line; a metro station in Athens; a Great African lake; one of the world’s biggest waterfalls; at least two mountains; a dam; the capital of the Seychelles and two whole Australian states. Victoria is also the subject of at least 45 statues in England alone, meaning her face – and that’s a conservative estimate – is on about one in three statues of named women in the country.

Victoria is an awkward one for women’s historians because she was both one of the most powerful women in history and a bit of a misogynist. She’d choke at the thought of being remembered alongside suffragettes. She called the fight for women’s rights a “mad, wicked folly” and preached obedience and submission to one’s husband. But Victoria’s presence on the throne was a powerful argument for feminists. How could a woman rule the empire but her sisters not even be allowed a vote? Historian Arianne Chernock makes a convincing argument that the British monarch’s limited powers today are a direct consequence of Victorian politicians’ effort to minimise a woman’s influence: “Misogyny (...) played no small role in modernising the monarchy.”

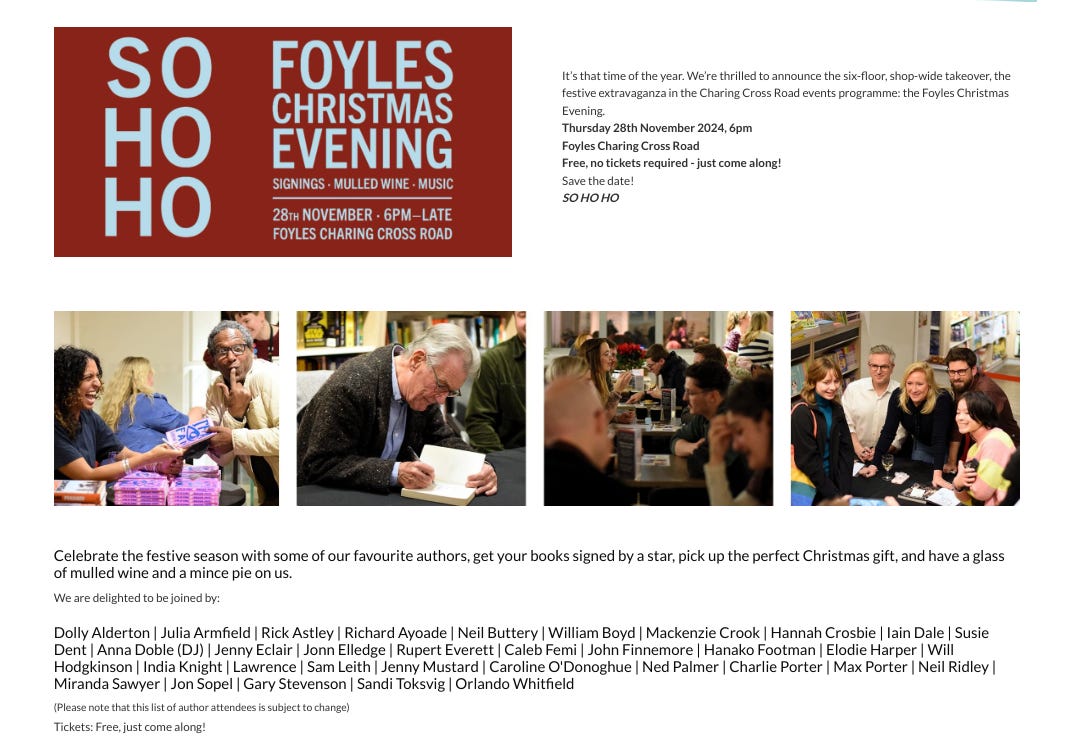

A brief commercial interruption from Jonn…

Come along, and say hi! Right, back to Isa…

Blackhorse Road

In the 1920s, on the industrial estate now better known as the Walthamstow Beer Mile, there stood the Achille Serre factory, named after the Frenchman who introduced the UK to dry cleaning. With 1,700 workers at its peak, the factory was big enough to employ its own, all-women fire brigade.

Though women were not admitted as city firefighters, private employers had fewer qualms. Women formed firefighting units to defend their own schools and factories as early as 1878 and took on bigger missions during both World Wars. In 1928, the women of the Achille Serre Ladies Fire Brigade served in outfits more reminiscent of Sailor Moon than anything you’d want to run into a burning building in.

The London Fire Brigade wouldn’t employ a woman in an operational role until 1982 or have a female commissioner until 2017.

South Tottenham

For the purpose of this article, South Tottenham is really Seven Sisters, so I finally have an excuse to research the question I ask every time I pass the station: who the hell are these Seven Sisters?

They’re actually trees, seven elm trees that were either planted or spontaneously grew in a ring formation six or seven centuries ago, and became shorthand for the location. According to local folk tales, the trees were planted by seven sisters who wanted to commemorate their time together before moving into adult life. Another tradition sees the trees planted by the sisters of Robert the Bruce, king of Scots. Sure, the family had an estate in Tottenham (Bruce Castle) but as far as I can tell, Robert had only six sisters (and they all paid the price for their brother’s rebellion).

The trees have been replanted several times over the centuries, always by seven sisters. The latest replanting was in 1996 with no less than five local families of seven sisters. Let’s see what declining birth rates do to that tradition.

Harringay Green Lanes

Around the corner at 54 Wightman Road in what was once a butcher shop were the headquarters of the Black Liberation Front, a pan-Africanist and socialist organisation founded in 1971 by former members of the Black Panther movement.

Black women struggled to find a place of their own both in the women’s rights movement and the black liberation movement. Gerlin Bean, one of only two black women present at Britain’s first National Women’s Liberation Conference in Oxford in 1970, created a women’s caucus within the BLF. Its activists focused particularly on improving the conditions for incarcerated people. In the BLF’s popular newspaper Grassroots, the Sisters column offered up inspiring black women role models, and took on issues such as discrimination in access to contraception, white-coded beauty standards or the absence of black women in the history books.

Crouch Hill

Crouch End saw the first recorded women’s club football match, on the south slopes of Alexandra Park, in March 1895. The North team led by Miss Nettie Honeyball (yes, she made that up, and I love her for it) beat the South 7-1 before an impressive crowd of 11,000 spectators.

Among the players was 19-year-old Emma Clarke, a confectioner’s apprentice and the first known black woman footballer. Daisy Allen, the North’s star left-winger, was, according to one report, only 11 years old. The players wore so-called “rational dress”, a fashion already made popular with the growing use of bicycles among young women: every inch of skin covered but with loose blouses and knickerbockers. No corset, no petticoats. That allowed for plenty of elbow action, too.

Honeyball (this won’t get old) had formed the British Ladies Football Club the year before, under the patronage of war correspondent and explorer Lady Florence Dixie. She told the Daily Sketch: “I founded the association (...) with the fixed resolve of proving to the world that women are not the ‘ornamental and useless’ creatures men have pictured.”

The BLFC played more games in quick succession in the spring of 1895, each time to large crowds, even beating those attending men’s games. Women’s football continued to grow in popularity in the early 20th century: by 1921, there were around 150 women’s football clubs in the country, who played to crowds in the tens of thousands and could sell out stadiums.

That’s the moment the English Football Association chose to declare the game “not suitable for females” and ban women’s teams from FA grounds. Without decent venues, the women’s sport petered out.

Upper Holloway

HM Prison Holloway was Europe’s largest women’s penitentiary. The castle-like structure was built in 1852 with at its entrance – so subtle – two huge griffins holding keys in their claws.

Sisters Christabel and Sylvia Pankhurst were both detained here, as were countless suffragettes whose names were not recorded by the history books. This is where the sickening scenes of force-feeding occurred, and the pavement outside the prison became a site of protest for the prisoners’ supporters.

Holloway also held Irish Republican women around the same time. British fascist Diana Mitford was detained here in 1940, and later joined by her husband Oswald Mosley. Ruth Ellis was hanged here in 1955 for the fatal shooting of her lover, the last woman to be executed in the UK. Emma Humphreys spent a decade at Holloway for the murder of her boyfriend, who had been violent, before the Court of Appeal reduced her conviction to manslaughter and released her in 1995. The case changed the way courts consider “battered women” who kill a long-term abusive partner.

The prison closed in 2016 and – Jonn’s regular readers will appreciate this – is to be reopened as a housing development in 2027.

Gospel Oak

Let’s find some peace at the end of this sometimes disquieting journey with a stroll in Hampstead Heath, and perhaps even a swim.

There was, from the early 1800s, only a mixed bathing pond in the Heath, with Thursdays reserved for women. The Men’s Pond opened in 1893 with ladies admitted on Wednesdays. Finally the Kenwood Ladies Bathing Pond opened in 1926 with a shed for changing, cubicles for hire and a diving board.

Are you enjoying the trees? You should. There were far fewer a century ago, and plenty of unobstructed views of the ladies’ pond. Men would ride their bicycle up to the heath and line the banks hoping to catch a glimpse of bathing women. For the sake of public order, authorities banned topless sunbathing.

If you enjoyed that - and what kind of male chauvinist monster would you be if you hadn't? - you can sign up to Broadly Speaking to hear more from Isabelle here.

A CORRECTION: The original draft of this post identified the wrong Mitford sister; have corrected!

Really enjoyable read, thank you both!