A Southend native messaged me about the map in a recent newsletter, to express a weird sort of pride that his home town managed to include some of both the most and least deprived areas in England. In passing, he asked if I knew where the conurbation’s name came from.

I did: it was originally the “south end” of Prittlewell, little more than a couple of fishing huts on the outskirts of the medieval market town inland. Then, in 1803, Princess Caroline of Brunswick – the future wife of the future George IV; a sort of regency Princess Di – stayed by the seafront on the advice of her doctors, and the local tourist industry went nuts. A few decades later, helped out by the arrival of the railway, Southend was a thriving resort town, complete with the world’s longest pleasure pier (2,158 metres!). Prittlewell had been relegated to the status of a suburb.

Even so, it is still not, in any serious sense, “on sea”. The land visible on the horizon isn’t France, but Kent, only a few miles away. I have yet to recover from that childhood disappointment, let me tell you.

Anyway, all this got me thinking: where do our cities get their names? Here are a few of the biggies.

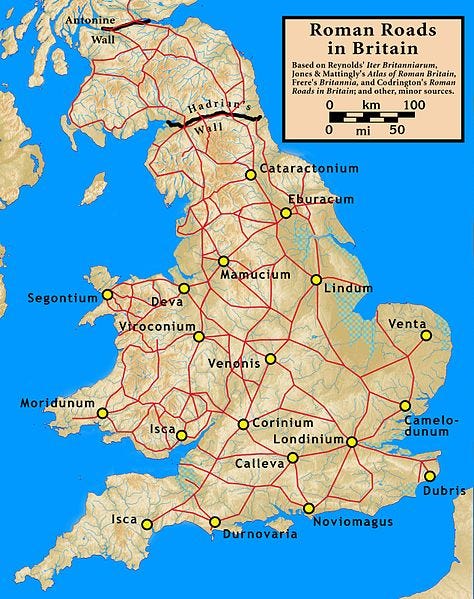

A gratuitous map of Roman Britain. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Birmingham – Originally the Old English “Beormingahām”, meaning the home of Beorma’s people, though whether Beorma was the settlement’s leader, or some kind of ancestor, or someone who existed at all, we have no idea. However, the “-ingahām” suffix is apparently most common in the earliest Anglo-Saxon settlements, so Birmingham probably existed by the early 7th century at the latest – even if it’d be another 1,100 years or so before it became a remotely big deal on the national stage.

Where the original Birmingham stood, incidentally, is another thing no one seems to know – it might not have been a single settlement, but a collection of farms – but by the 12th century it was centred on a market roughly where St Martin in the Bullring stands today.

Bristol – Originally “Brycgstow”, meaning the meeting place (stow) by the bridge (the other bit). By the middle ages, the “Bristolian L” – a quirk of the local accent in which words ending in vowel sounds get an extraneous sound added on to the end of them – meant the town’s name had an “L” on the end of it.

The non-L version survives in the surname “Bristow”, as in famous darts player Eric, which just means “someone from Bristol”. Should you fancy a meeting, the stow is still there: it’s now College Green.

Leeds – Charmingly, no one seems quite sure. The word isn’t Anglo-saxon in origin, so experts agree it was probably an older, Brittonic (that is, British Celtic) name for the area – but whether it comes from a strongly flowing river, or animals in heat (no, really) is a matter of fierce debate.

Either way, its original form “Loidis” first appears in the work of the Venerable Bede around 730, but that seems to refer to an area, possibly a forest, rather than a settlement. By the time of the Domesday Book of 1086 it’s clearly a place where people actually live.

Liverpool – A pool which is thick and muddy or – more interestingly, but less plausibly – full of eels (“elver-pool”).

That’s actually quite a boring bit of etymology, so let’s note that this is one of the few significant English cities whose foundation we can actually date, not just to the nearest century but to a specific day: 28 August 1207, a Tuesday, when King John issued letters patent inviting settlers to the new borough of “Livpul”. Being King John, his motives were less about doing nice things for his people than about undermining the local aristocracy – an earl, named Ranulf – so that he could get troops to and from Ireland without his permission. The city only really boomed after its pool became the world’s first commercial wet dock in the 1710s; it closed again in 1826. The Liverpool One shopping centre now stands on its site.

Manchester – Started out as a Roman fort named “Mamucium” or possibly “Mancunio”, in what is now Castlefield, but the name seems to be older even than that. The “mam-” bit is thought to come from either the Brittonic word for mother, possibly referring to a goddess who hung out in the rivers Medlock or Irwell; or the Brittonic word for, er, breast, referring to the fact a local hill looked like a tit. The -chester bit is the Old English word for “castra” which means, well, a Roman fort.

Newcastle-upon-Tyne – Another Roman fort, Pons Aelius (“Aelian Bridge”), a settlement founded in 122 and named for the clan name (“nomen”) of the Emperor Hadrian. (He also, you’ll recall, gave the area some wall.) After the Romans left in the 5th century, the area became known as “Munucceaster” – Monk-chester – meaning, basically, a fort where monks lived – but the fortifications clearly weren’t up to much, because they were destroyed by some Danes in the 9th.

When the Normans invaded in the 11th century, and built a whole bunch of castles to help out with their generally-oppressing-the-locals thing, one of the sites they chose was the strategic crossing of the Tyne: it was that new castle which gave the site its name. Its ruins are still there, and are well worth a visit – as is the Bridge Hotel pub, which stands just next door.

Nottingham – The estate or home (ham) of the Snotingas, a tribe whose name may come from the word “snottenga”, meaning “caves”, or which may mean they were led by a bloke called, er, “Snot”. The area around St Mary’s Church, known more recently as the Lace Market – which is, oddly, nearly a mile from the bridge over the River Trent, which one might assume to have been the centre – is probably the original settlement.

Nottingham, incidentally, is the largest city in the UK to give its name to a traditional shire county.

Sheffield – A field on the River Sheaf, whose name means “divide” or “separation” (it might have the same root as the “shed” in “watershed”). The field in question was probably a clearing at the point where it joins the River Don, just to the south west of the Blonk Street bridge, and for most of the middle ages was the site of Sheffield Castle; but that was demolished by order of Parliament during the late 1640s, for the heinous crime of having been a stronghold for the losing side in the civil war.

The River Sheaf is still there, flowing beside the famous Park Hill flats, even if it is now buried beneath the city centre.

Oh – and no one really seems to know where the name London came from either. Obviously it started life as “Londinium”, a settlement built by the Roman army to defend its new bridge, not long after it invaded in the year 43. But that could be a Latinisation of “Plowonida”, meaning “fast-flowing river”; or of “Llyn din”, meaning “lake fort” (the lake in question was presumably the wide, still, Pool of London, just downstream of London Bridge; though how you can have a fast-flowing river and a pool is beyond me). We just don’t know.

This has not stopped anyone speculating. In his 1136 work Historia Regum Britanniae, for example, Geoffrey of Monmouth suggests it’s from the name of King Lud, the city’s mythical founder and ruler, who was apparently around about a century before the Romans and who is meant to be buried somewhere on Ludgate Hill. Which is a pretty neat trick for a man who probably didn’t exist.

I could go on – in fact, one day I might, because there are a lot more cities than this (I’ve only done England for a start). And so, this might be the first in a series. Please do let me know if you’d appreciate that – or, come to that, if you’d really rather I didn’t.

If you liked this email, and would like to receive one every week containing similar goodies, then you can become a paying subscriber for £4 a month, or £40 a year: either way, that’s less than £1 a week and, hey, I’ll even throw in your first month free. Just click this link and you’re in.

If you liked this email, and would like to receive one every week containing similar goodies, but are currently in a situation where you can’t really justify paying for some nerd’s substack (unemployed, underemployed, impoverished student, and so forth)... then just email me, and I’ll give you a complimentary subscription, no questions asked.

If neither of those things apply then you don’t have to do ANYTHING. More free content will intermittently appear in your inbox, because I’m just that nice.

In the mean time… Questions? Comments? Suggested topics? Email me.