It’s the demographics, stupid

Age explains a lot more of British politics than we sometimes give it credit for.

Welcome to another instalment of my occasional series of thoughts too long for a tweet. Because sometimes that thread really should have been a blog. If you want to subscribe and get more of this nonsense, click below:

A repeated refrain over the last couple of years: Labour has lost touch with its working class roots, and that’s why it keeps losing. “Labour’s lost working-class voters have gone for good,” ran the headline on a Guardian article by the Cambridge politics professor Chris Bickerton in the days after the 2019 election. Likewise the headline from Tony Parsons in the Sun at around the same time read: “Labour got what they deserved for abandoning their traditional working class supporters”.

Sir Keir Starmer, looking worried at Chatham House in 2013. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

I’m not going to talk about the fact that the “working-class” people in question tend, suspiciously often, to be older, home-owning, even business-owning non-graduates; meanwhile younger, more precarious renters and BME people tend to be excluded from the definition of “working class”, by virtue of their education or the fact they live in London or the fact “working class” quite often carries a silent “white”. Nor am I going to dwell on the fact that the people making this argument are quite often doing it cynically (Tony Parsons? Really?). Everyone knows those arguments already, and we’re none of us free from cynicism, and what’s the point.

Instead, a simpler proposition that’s a lot easier to, if not prove, then at least demonstrate. In a lot of the traditional Labour areas that have slipped away from the party, the problem isn’t class, but age.

Consider Workington in Cumbria. The town got its first Labour MP when it first became an individual constituency, in 1918. It stayed Labour for most of the next century: the Tories briefly held it after a 1976 by-election, but lost it by 13 points in 1979, and it stayed solidly Labour ever after.

Until, in 2019, the Tories took it again. Labour were suddenly 10 points behind.

Check out the demographic stats, courtesy of the Centre for Towns’ data tool:

The demographics of Workington. Image: Centre for Towns.

That chart’s a little hard to read, so here’s another to make things clearer. The blue line is the old age dependency ratio – the number of over 65s for every 100 people aged 16 to 64 – in Workington; the red line is the national average:

The old age dependency of Workington, compared to the national average. Image: Centre for Towns.

The share of Workington’s population that are, statistically speaking, in the first half of their life has fallen. The share in their second half has risen. In 1981 it was slightly older than the national average. By 2011 it was significantly older. It seems very likely that when the results of this year’s census come out it will have become older still.

You can see similar results in a lot of the places where Labour have lost ground in recent years. Hartlepool is another seat which Labour has always held, but the bookies currently have the Tories as favourites to take it in next month’s by-election.

The demographics of Hartlepool. Image: Centre for Towns.

Demographically it looks a lot like Workington, 100 miles away on England’s opposite coast:

The old age dependency ratio of Hartlepool. Image: Centre for Towns.

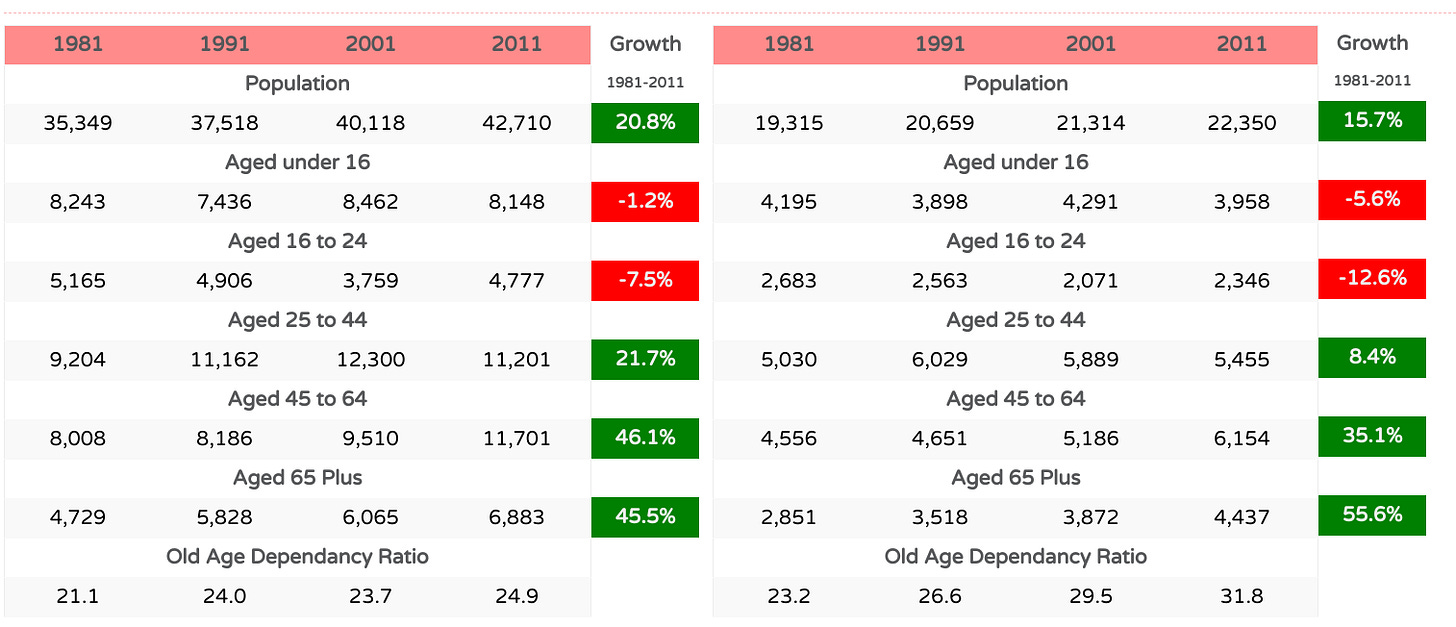

Lastly, a two-for-the-price-of-one deal. The data on the left is for Worksop; on the right is for Retford. These are the two biggest towns in the Nottinghamshire district of Bassetlaw, which Labour had held since 1935, but which in 2019 saw a Tory victory after an 18.4 point Labour to Tory swing, the largest in the country.

The demographics of Worksop (left) and Retford (right). Image: Centre for Towns.

And would you believe it: these are two more towns which, by 2011, had seen a massive growth in their older populations, matched by a slight fall in their younger populations.

The old age dependency ratio of Worksop (left) and Retford (right) in blue, compared to the national average, in red. Image: Centre for Towns.

This demographic shift, I suspect, can be explained by changes in the labour market. Since 1981, the British economy has seen declines in the number of manufacturing and resource extraction jobs (which are based all over the place, because factories take up a lot of space and you can only put mines where the coal is). It’s also seen an increase in the number of service jobs (which, at the higher ends in sectors like law and finance, tend to cluster in big cities). Over the same period, we’ve seen a big increase in the share of the population going to university, which means a big increase in the share of the population leaving their home towns at 18, moving to London at 21, then never moving home.

Roll the tape forward a couple of decades and you get the situation we’re in now – where Labour is piling up more and more votes in safe seats like Manchester Central or Hackney South, but solid Labour towns are turning Tory because they’re increasingly dominated by older people who, the data suggests, are more likely to vote Conservative.

The strange thing is not that those towns are turning Tory: it’s that they took so long to do so.

These are only a few examples: I haven’t consciously cherry-picked to exclude towns that don’t fit my thesis, but nor have I systematically checked they don’t exist. But nonetheless, I think it’s a decent working theory: Labour’s current travails have less to do with its ability or otherwise to speak to working class voters than the fact Britain’s demographics are against it.

You received this email because you signed up to the mailing list for The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything. To guarantee you receive the full weekly newsletter every Wednesday at 4pm, including some comment on the news, an article on something nerdy, a map of the week, and more – or just because, hey, you like this stuff, and you think I deserve it – you can become a paying supporter by clicking the button below. At £4 a month, or £40 a year, I am an enviably cheap date.

It’s a similar pattern to the age profile of the Leave/Remain division on Brexit. As long as these are cohorts (as opposed to views changing with age) it augurs well for the future for Labour and for a pro-EU stance