No, that isn’t technically a city, and no, I don’t care

Official city status, and why it sucks.

Welcome to the latest fortnightly extract from the NO(NQ)E archive. This week, some thoughts on the essential ridiculousness of the British city.

As ever, if you’d like to get this stuff as it comes out, and read all the other stuff that never escapes the paywall too, you can become a paying subscriber here:

The largest city in England is Birmingham. It is followed, in this order, by Leeds, Sheffield, Bradford and Manchester. The second smallest is Wells, on the edge of Somerset’s Mendip Hills, home to just over 10,000 people.

The smallest of all is London.

Those last paragraphs are, officially, true. Therein lies the problem.

It’s eight years now since I started Having Opinions About Cities on a professional basis. In that time I have tweeted thoughts about cities as varied as Reading and Middlesborough, Bournemouth and Huddersfield. And, over and over, those tweets have received a predictable stock response: “That isn’t a city, though.”

This is annoying for several reasons, but the most annoying of them all is that it is, technically, correct. The UK officially has precisely 69 cities (nice): read Wikipedia’s list, and you will not find any of the places I listed in the previous paragraph. You will, however, find such bustling urban centres as St Davids (pop. 1841), in the far west of Wales...

...or St Asaph (pop. 3,355), in that country’s opposite corner:

To give you a sense of quite how enormous these megalopolises are, here’s a chunk of Manchester of the same size and shown at the same scale:

That’s not even – not even close to – the entire city centre. Meanwhile St Davids is the sort of place that would have to conduct a major programme of housebuilding and public works if it wanted to be taken seriously as a village. Yet the British state, in all its infinite wisdom, has looked at it, and decided, “Yep, that’s a city, right enough”.

How did this happen? As with so many of the more obviously ridiculous aspects of the British state, much of it comes down to the awkward interaction between centuries of medieval precedent, the Industrial Revolution, and the political ambitions of Henry VIII.

Once upon a time, city status was an informal sort of affair: a royal charter wasn’t seen as granting city status, merely as recognising it. This meant that settlements that happened to have grown up around cathedrals were treated as cities because, well, they always had been.

Then the Reformation happened and, to consolidate his hold on the church, in the early 1540s everyone’s favourite morbidly obese Tudor wife-murderer created six new cities via letters patent. Now, unless it had been considered one for centuries, a settlement needed government permission to count as a city.

For the next 300 years or so this wasn’t a problem, but then a load of people started descending on the new industrial centres in search of jobs. In the century after 1811, the population of Manchester grew by a factor of seven. Suddenly, city status wasn’t about recognising something that had always been the case, it was about acknowledging that a place had arrived. So the boomtowns began petitioning the government.

It was in an attempt to impose some order on this that, in 1907, the Home Office established three criteria necessary for a place to count as a city – a minimum population of 300,000, a good record of local government, and a “local metropolitan character”. True to form, however, no one in government bothered to tell anybody else what those criteria were, and anyway immediately started ignoring them.

Changing local authority boundaries confused things further. St Davids lost its city status in 1886, when a local government reorganisation meant it officially ceased to exist, and so there was nobody to complain. The same happened to Armagh. Both got the status back in 1994, “in recognition of their important Christian heritage and their status as cities in the last century”, even though St Davids is only as a community council – little more than a parish – and Armagh exists only in the title of the (deep breath) Armagh City, Banbridge & Craigavon Borough Council. Other places haven’t been so lucky. Rochester lost its own city status by accident in 1998 when it too ceased to exist and became part of the new borough of Medway. It’s still not allowed to use the title.

This isn’t the only way council boundaries have proved problematic. The reason that the list of the largest cities in England at the start of this article looks so weird is because it’s counting the population of fairly arbitrarily defined council areas, not anything one might experience as a city. London is officially the smallest city in England by population because the London in question is the City of London where only around 7,000 people live. Greater London is not officially a city at all. Neither is Greater Manchester. Meanwhile chunks of Cumbrian countryside are part of the City of Carlisle. It’s madness.

Size isn’t the only factor that should determine what counts as a city, of course. Nearly 3,000 years of human history passed before anywhere met that Edwardian minimum of 300,000 people (the first was probably Alexandria, in Egypt, around 200BCE; it’s on page 41 of my book). And surely there is a case that Truro, the capital of Cornwall, has a better claim than Southend, essentially a coastal outpost of London, even though the latter is around 15 times the size. But if the residents of St Davids officially live in a city, while those of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets do not, surely we can agree that something’s gone wrong.

So: yes, officially, St Asaph is technically a city, while Middlesbrough technically isn’t. But this is not an argument against the city-ness of Middlesbrough: it’s an argument against the entire, nonsensical edifice of official city status.

(Incidentally, in case you missed here, I’ve already ranked every place currently applying for official city status, by order of plausibility. If you missed it, you can check it out here.)

Map of the week

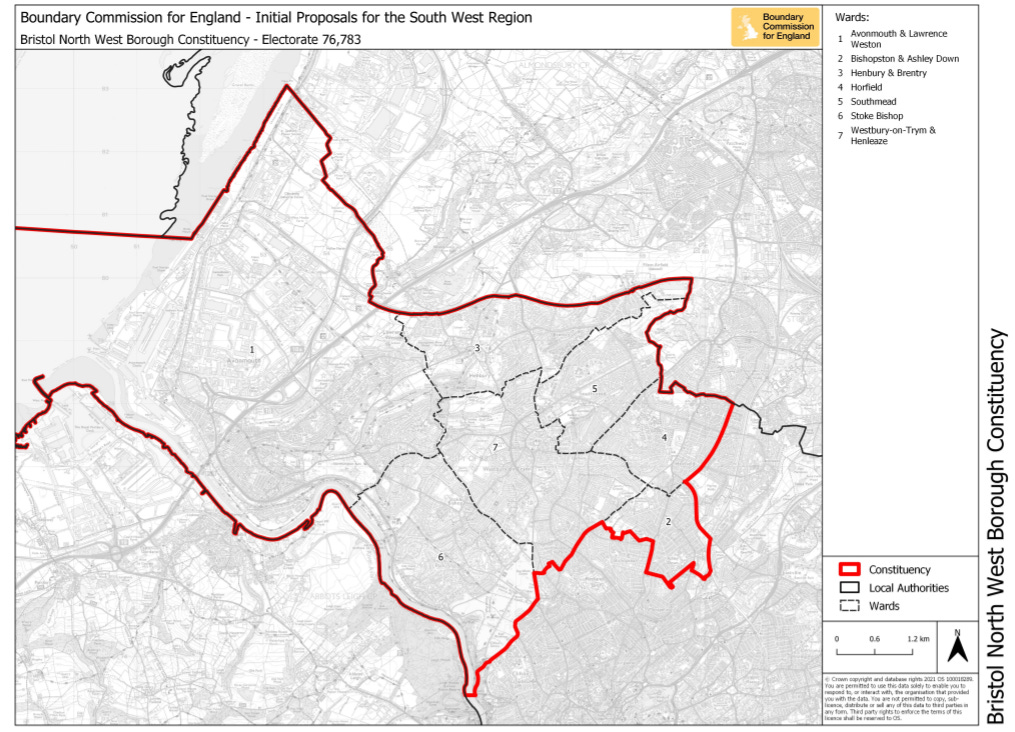

This week’s entry comes from the Boundary Commission for England, and shows its proposals for the slightly rejigged Bristol North West constituency.

Not very promising, you think? I beg to differ. Look to the left:

Something strange is going on: the proposed constituency seems to extend into the Bristol Channel. Quite a long way into the Bristol Channel, in fact.

About 20 miles or so, by my estimate.

What gives?

Well, for one thing: this isn’t the Boundary Commission’s doing. The commissioners are using existing council boundaries, and those of the City of Bristol really do extend several miles out into the Channel, as far as the islands of Flat Holm and Steep Holm. In 2007, the city’s then Lord Mayor Royston Griffey JP (this is, apparently, a real name) undertook the ancient rite of “beating the bounds” of the city. He had to borrow the Royal Navy’s HMS Ledbury to do it.

The existence of Bristol’s maritime extension seems to go back a very long way: Russ Garrett, who last year live tweeted his attempt to get to the bottom of all this, points to a document outlining it that dates from 1373. That was the year parts of Gloucestershire and Somerset were merged into the newfangled City and County of Bristol – a sort of medieval combined authority, a way of dealing with the awkward fact that one of the major cities of 14th century England was technically split between two counties and thus two sets of authorities. Whether the boundary dates back even further than that, nobody seems quite sure – but the logic seems to have been that, by extending the city’s territory below the low-waterline into open sea, Parliament was giving the port city control of shipping in the channel. It may have been tied up with the port’s defence, too: at some points, at least, the two islands were fortified.

Bristol is not unique: other councils including Brighton & Hove, Torbay and Aberdeen also include stretches of sea. And the City of Norwich technically includes a long stretch of the River Yare, well outside its boundaries. (It may not be a coincidence that Bristol and Norwich were two of the biggest cities in medieval England.)

But one last oddity about that seems worth noting: only one of those two islands that mark the boundaries of the city is technically a part of it. Why isn’t Flat Holm in Bristol? Because it’s in Wales.

I love historic boundaries, I really do.

Thanks to Russ Garrett and Alex Partridge for the tweets which brought this one to my attention.

This is an extract from the (paywalled) archive of the Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything. If you want to get all of this stuff as I write it, instead of several months after the event, and want to read the other roughly 80% of the newsletter I never take out from behind the paywall, why not become a paying subscriber? For just £4 a month, or £40 a year, you’ll get a newsletter containing several of them every Wednesday. Hey, I’ll even throw in your first month free. Just click this link or press the button below.

Can’t currently justify paying for some nerd’s substack (unemployed, underemployed, impoverished student, and so forth)? Just email me, and I’ll give you a complimentary subscription, no questions asked.