On Finland, and other places that don’t exist

Some thoughts regarding the internet’s strange habit of declaring very real places to be imaginary.

Hello everyone. Christmas is coming. Seems to come round faster every year, doesn’t it? The lights, the food, the parties, the desperate need to find presents for relatives…

In unrelated news, here’s an extract from Conspiracy, the book by Tom Phillips and I published by Headline last July, which is currently available from all good book shops.

Consider the question – because it turns out that there is a question – of Finland.

If you know anything at all about Finland, you probably believe that it’s a large but sparsely populated country in northern Europe, which lies between Sweden and Russia, and is famous for its lakes, forests, saunas, and winning Eurovision by fielding a heavy-metal band dressed as monsters. But you would be wrong about all of those things, because, according to some corners of the internet, Finland has never existed. That large but sparsely populated stretch of northern Europe? Just another bit of the Baltic Sea. Its capital, Helsinki? Actually eastern Sweden. All those people, who confidently believe themselves to be Finns? Also from eastern Sweden, or western Russia, or northern Estonia. Because there is no such thing as Finland.

All this started, as so many of the worst things do, on Reddit. In 2015, a thread on the AskReddit subforum posed the question, “What did your parents show you to do that you assumed was completely normal, only to discover later that it was not normal at all?” A user named u/Raregan gave the example of the Finland conspiracy theory.

The roots of the plot, he explained, related to fishing rights. Japan, you see, has an almost insatiable appetite for sushi, consuming far more fish than it’d be allowed to take from the seas by international law. To get around this problem, so the theory goes, it conspired with the USSR to invent a country lying off Russia’s Baltic Coast, in a place where it could fish undisturbed. “After all,” explains an account of the theory on the r/FinlandConspiracy subreddit, “nobody’s going to expect fishing regulations to be broken in a place where everyone thinks there’s a landmass, will they?” Indeed.

The resulting catch was then transported via the suspiciously useful Trans-Siberian Railway, under the guise of Nokia products. This apparently explains both why Nokia was so successful in Japan despite hardly anyone there owning a Nokia phone, and how Nokia managed to become the largest Finnish company when, as everybody knows, Finland doesn’t exist.

As to the world’s other 191 or so countries – at least some of which, one assumes, might have noticed that the Baltic Sea is roughly twice as big as it was supposed to be – the reason they’ve gone along with all this is simple: the Finland myth gives the rest of us something to aspire to. Imagine a country with great education, good healthcare, gender equality and brilliant literacy rates. Finland is, in more than one sense, a dream.

Oh, and a clue to the truth can be found in the name. Finland is secretly just a place for the Japanese to fish. What do fish have? Think about it.

The notion that a huge geographical region, containing people who you might have literally met, is nothing but a lie is so outlandish that you could be forgiven for thinking that this would be a one-off. You would be wrong. The online world has been declaring bits of its offline counterpart to be Narnia without the talking animals for about as long as there has been an internet to do it on.

Bielefeld is, at least according to the official narrative, the eighteenth-largest city in Germany. It is home to no significant corporations or public institutions; no tourist attractions; no major river. It has no significant features whatsoever.

So in 1994, after passing an autobahn sign on which all the signs to Bielefeld had been taped over, a student named Achim Held came up with a theory to explain how a city of 340,000 people could be quite so unknown: it didn’t exist. This would explain why he had never met anybody from the city, nor anyone who had even visited it. Who could be propagating such a diabolical conspiracy, he asked in a Usenet post? A group known only as “SIE”: “They”.

A generation later, and there’s one thing everybody does know about Bielefeld: that it’s really funny to pretend it doesn’t exist. In 2010, film students at Bielefeld University made a film about the conspiracy, and exactly what SIE wanted. By 2012, Chancellor Angela Merkel was cracking jokes about the non-existence of a fair-sized German city.

By 2014, the city itself was in on the joke, promoting its 800th anniversary under the slogan “Das gibt’s doch gar nicht”: ‘That cannot be real’. Five years after that, it was offering €1 million to anyone who could offer ‘incontrovertible evidence’ that it did not exist. When the prize went unclaimed, the city announced that it definitely did exist after all, and declared the joke over. Whether that’ll be enough remains to be seen.

Other places that the internet has declared to be unreal in much the same manner have included the US state of Wyoming, the Brazilian state of Acre or the Italian region of Molise. All these places fit a particular profile. They are peripheral, sparsely populated, off the tourist track – and famous for nothing other than their own questionable ontological status. The “proofs” they don’t exist can thus follow the same logic as that which Held applied to Bielefeld. Have you ever been to X? Do you know anyone who’s from X? Do you know anyone who has ever been to X? If the answer to all three questions is ‘no’, then, well, it stands to reason that X probably doesn’t exist, doesn’t it?

The biggest geographical conspiracy theory of all, however, doesn’t fit this pattern. It involves a place that you are all but certain to know someone who has visited, or even someone who calls it home.

In 2018, a Swedish Facebook user named Shelley Floryd racked up nearly 20,000 shares with a post outlining ‘one of the greatest genocides in history’. Over eighty years, she claimed, the British Empire had loaded 162,000 criminals on to ships, ostensibly with the intention of deporting them to its new prison on the other side of the world. “In reality,” she wrote, “all these criminals were loaded off the ships into the waters, drowning before they could ever see land again … They never reached that promised land.” They couldn’t have: Australia, it turns out, is a hoax.

But what, you may be wondering at this point, of all the flights to Australia, some of which you might have even flown on? Actually, they’re to islands, or perhaps parts of South America. (The entire aviation industry is in on the scheme.) Your Australian friends? “They’re all actors and computer-generated personas, part of the plot to trick the world.” In other words, as a sort of subplot of the “Australia is not real” conspiracy, truth-seekers are free to indulge in additional theories such as “Hugh Jackman never existed”, “Kylie Minogue is a computer avatar”, or any other claim that involves the non-existence of any Australian they happen to have taken against.

All this, Floryd wrote in her post, constituted “one of the biggest hoaxes ever created”. This, notes an article on Culture Trip, is “an extraordinary statement in itself – if the fabrication of the sixth-largest nation on Earth isn’t the biggest hoax ever created, the No.1 ruse must be an absolute whopper”.

The original post is long gone (although, the same article notes, whether it was the intervention of nefarious governments or the abuse from angry Australians that did it remains unclear). But its footprint remains in the form of memes and write-ups by media organisations from countries, real or imagined, all around the world.

And it was, in any case, not the first time that the idea that an entire continental landmass was a fiction has found its way onto the internet. A 2006 post on the Flat Earth Society forum also claimed that Australia didn’t exist, though it made no attempt to give a motivation for the fabrication. The message was preceded by the disclaimer, “Although I believe that the Earth is flat, this is not actually part of the Flat Earth Theory”. Many of the Flat Earthers replying either mocked the post, or replied, simply, ‘Evidence?’

That does not mean there’s a hard line between trolling and ‘real’ conspiracy theories such as the flat Earth theory, however. Ideas intended as jokes may not be received that way, and those who go looking for evidence will soon encounter other theories. If the YouTube algorithm means that those researching the existence of Bielefeld soon find themselves watching “Flat Earth Clues”, how does it really matter that the original post was a joke?

These big, geographical conspiracy theories highlight another problem: how can you actually prove that Australia exists? Maps can be fabricated; satellite photographs altered. You may believe you’ve been there, but you travelled by plane: all you really know is that you’ve been somewhere. At some point, the evidence of our own eyes and ears ceases to be enough: we believe in Australia because the media and the authorities tell us it exists. But if you cease to trust that media and those authorities, what would be enough to convince you?

Incidentally, Raregan, whose real name was Jack, has said he doesn’t believe a word of the Finland theory he shared. Neither do his parents, who apparently had forgotten ever telling their kid this ridiculous lie and now find the whole thing hilarious. Nor, come to that, do many of the internet users enthusiastically asking how to break the news of Finland’s non-existence to their Finnish friends in the r/ FinlandConspiracy subreddit.

But that doesn’t mean nobody does. As Jack told Vice in 2016: “It’s honestly impossible to tell who’s joking and who’s serious sometimes.”

This is an extract from my new book, Conspiracy: A History of Boll*cks Theories and How Not to Fall For Them, co-written with the outstanding Tom Phillips. You can find another extract – on the phantom time hypothesis, the claim that 297 years of history never actually happened – here. You can buy a copy from all good bookshops, and also a bad one, and, given that it’s nearly Christmas, probably should

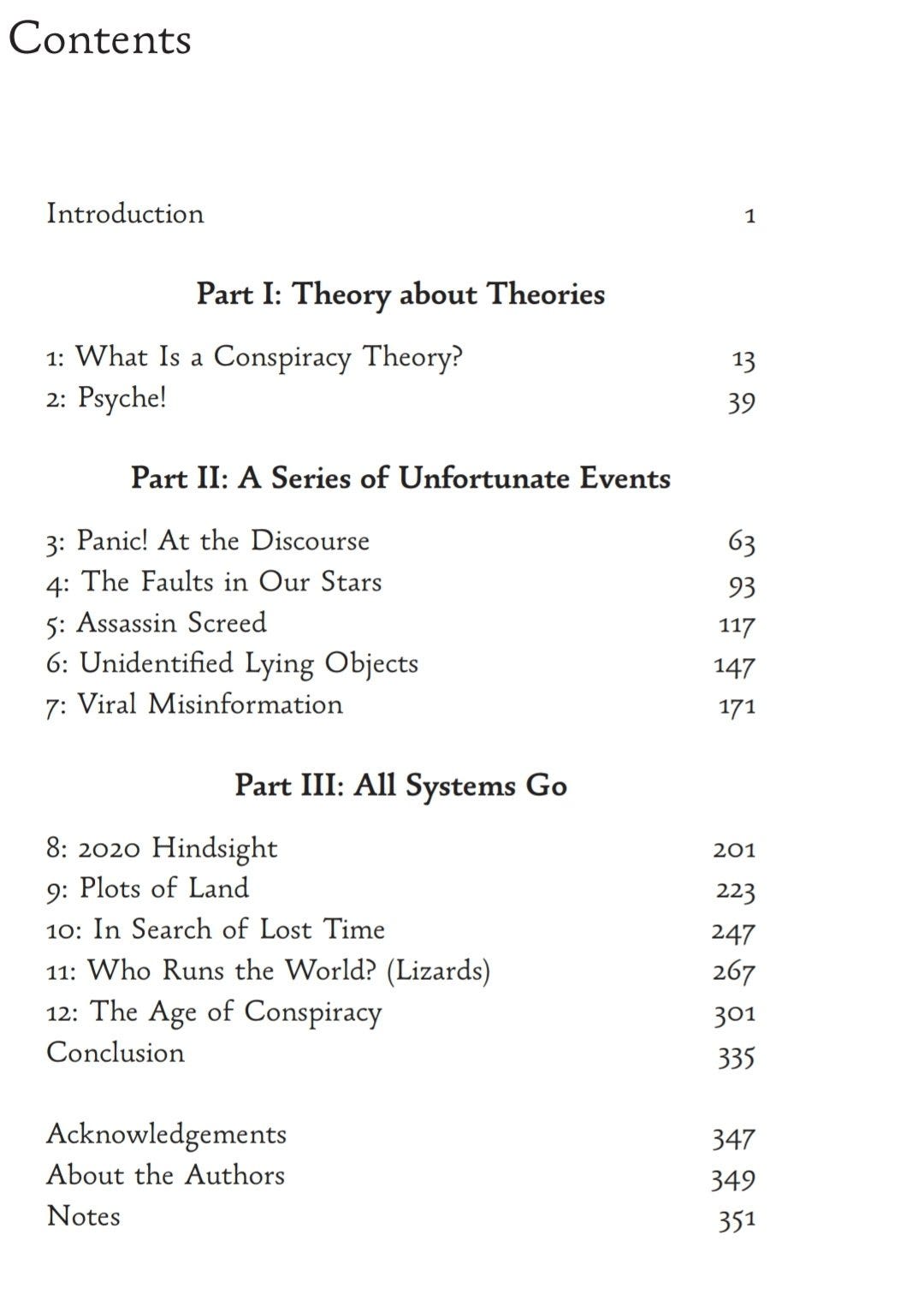

In case you want to have some fun guessing what’s in it, here’s the contents page.

I ordered a copy of the book the other day but it is now mysteriously running late. It was also out of stock in our two local book shops. Reddit says it’s because it doesn’t exist.

As someone actually from Finland, I can just say: thank God that this stupid joke is finally over. It became infuriating at warp speed to see idiots on Reddit go "Finland? Did you know that Finland doesn't exist? Japanese fishing rights?" in every article about Finland, as if they were the first one to invent that joke. I can imagine Bielefelders etc. feel them same.

I have a general rule of thumb: if one can avoid it, don't joke about someone's name, place of work or place of birth. Not because it's by definition offensive or crude or something, just because they have assuredly heard it far too many times before.