Royal absurdities and evil uncles

This week: why is Kate Middleton like the Princes in the Tower? (No, not that.) Also what’s the deal with the Channel Islands? And a map of Tory failure in Birmingham.

I’m going to say this upfront, for reasons that will become clear: I don’t believe, and do not mean to imply, that Kate Middleton is dead.

I think it possible, even likely, that Kensington Palace is hiding something – a more serious health problem than has been disclosed, say, or marital problems because the man she is married to is rumoured, ironically enough, to be no prince. Long stable reigns have often historically been followed by short, unstable ones, and we already know that the King is ill: that alone is surely reason enough for a hyper-cautious Palace to want to project an “Everything Is Fine!” vibe at moments when it is at least possible that everything is not, in fact, fine. But no: whatever is up, I don’t imagine for a moment that Kate Middleton is dead.

Nonetheless. What the swirl of rumour and conspiracy theories these last few days have inescapably put me in mind of is the Princes in the Tower.

Bear with me on this.

Edward V acceded to the throne on the death of his father, Edward IV, on 9 April 1483. He was, from the middle of the following month, resident in the Tower of London, as was traditional for kings awaiting their coronation.

But that coronation was first delayed, and then cancelled altogether. Edward’s lineage was declared illegitimate; his uncle Richard crowned in his place. Edward and his younger brother were sometimes seen playing in the grounds of the Tower; but as the summer wore on they were seen less and less, and eventually they disappeared altogether.

Exactly what happened to the boys is almost certainly unknowable, which is both why pretenders claiming their identities could become the focus for rebellions against the usurping Henry Tudor for the rest of the 15th century, and why “Ricardians” could be making mad TV documentaries claiming to have found “new evidence” well into the 21st. But we know, from the contemporary account of a visiting Italian friar, that rumours were flying that something had happened to the princes even at the time. It would have been in the interests of Richard III, newly crowned but already facing rebellion, to let the world see that the princes were fine. He didn’t do so. The obvious explanation – the thing his supporters have never quite been able to explain away – is that he couldn’t. And the obvious explanation for why he couldn’t would be playing to packed theatres, just across the river from the Tower, before the next century was out.

Today’s Palace will be, if anything, even more conscious of what the world is saying. They will know that people online, not all of whom are mad Americans, have been debating the Princess of Wales’ whereabouts for weeks. They will know that news agencies withdrew the picture meant to show everything was fine, on the grounds it seemed to have been doctored, which made a bunch of people think it showed things were the exact opposite of fine. And while the explanation for that is almost certainly something boring involving smartphone editing software, the press team presiding over this mess will, nonetheless, be mortified.

They will be aware, too, of the increasingly unhinged theories circulating, involving years’ old photographs of Kate’s face being edited onto the new photograph to show that it’s a pixel for pixel match, or comments about how brickwork seen through a car doesn’t quite line up with the brickwork seen behind it. (My favourite of these, a TikTok outlining a theory that the picture was taken last November with some of the colours switched up in the edit, literally begins with the premise that black is white, which, come on, that’s just brilliant.)

One could argue that we were told Kate would be out of circulation til Easter, that it’s not yet Easter and that therefore the rest of us should mind our own business – but it’s hard to square this with the Palace’s decision to keep pumping out doctored pictures of a happy, healthy princess. You may personally find the whole thing ridiculous, might think there are an almost infinite number of things going on in the world this week that matter more than the debate about the whereabouts of Kate Middleton, and in all honesty I’d struggle to disagree.

But the Palace, it is clear, does care about shutting this story down. It has a foolproof manner in which it could do that. And yet, it hasn’t used it. Why not?

The obvious reason for this – the source of all those conspiracy theories, the one with echoes of the events of 1483 – is that, for some reason or another, it can’t. Perhaps Kate looks or feels too ill for public appearances. Perhaps all is not right at home, and she’s refusing to publicly pretend otherwise. Perhaps, even, she’s just sick of the whole performing monkey aspect of monarchy, and who could blame her, even as they note it is literally what she is paid upsettingly well to do. Who knows?

The other possible explanation for why it’s all gone so horribly wrong is that the people whose job it is to manage the royals’ media coverage simply suck at their jobs and can’t cope with a situation in which it’s anything other than fawning. This has echoes in the media management strategies of other institutions like the Conservative Party or CPRE, so must be considered, to be fair, plausible.

All we can say for certain is that the Palace could shut this story down very easily simply by offering the world’s media a brief and unedited view of the Princes of Wales. For some reason or another, it hasn’t done so. There’s an excellent example from royal history that should remind them this is how rumours get started.

(I co-wrote a book about conspiracy theories, by the way. Just thought I’d mention.)

Some notes on four days on a Channel Island

I spent my weekend celebrating a friend’s birthday in a disused military encampment on Alderney, third largest of the Channel Islands. Fort Clonque sits on a rocky outcrop at the far end of a causeway that’s entirely submerged at high tide. One of a number built in the 19th century to defend Britain against rising French naval power and occupied by Nazis during World War II, it was rescued by the Landmark Trust in 1966, and today is holiday accommodation. It does not, alas, have wifi, or even very good phone signal. This obviously makes it the ideal destination for a bunch of media types on a jolly.

It is, in the right light, absurdly beautiful. So, come to that, is the island: despite being a rocky lump, 3 miles long and 1.5 wide, it’s home to puffins, guillemots, blonde hedgehogs and free range pigs, who I am absolutely kicking myself for not meeting because I didn’t accompany the rest of the party on their walk. It did, however, get me thinking about what exactly the Channel islands are and why they exist in their current form. So, once I was back on the phone networks, I did some reading.

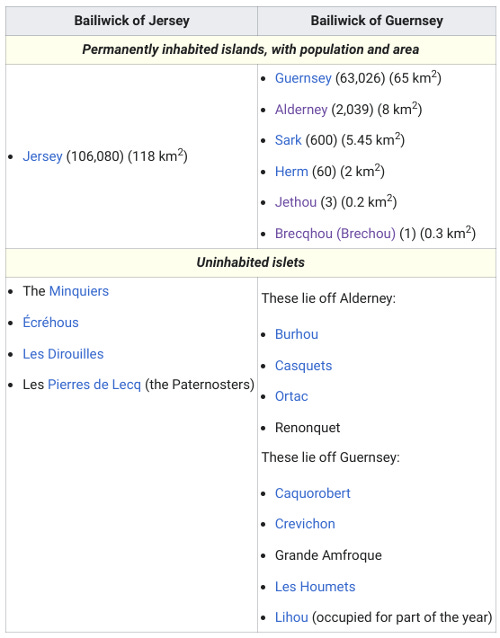

Firstly, I said Alderney was the third largest of the islands, and that’s true in terms of both population and area. There is, however, a heck of a drop after the first two. Here’s a list of all the islands, courtesy of Wikipedia:

At just over 106,000 even the largest, Jersey, has a population a third smaller than the smallest London borough, Kensington & Chelsea, and roughly on a par with Bedford. The population of Alderney, at a couple of thousand, would make for a not especially impressive village.

Regarding the even smaller islands: Jethou, which legend has it was connected to neighbouring Herm until a particular bad storm in the year 709, is generally home to the rich and reclusive. Ditto Brecqhuo, which since 1993 has been leased by the Daily Telegraph-owning twins, the Barclay brothers. The slightly bathetic reason its population is listed as “1” is because, in 2021, one of them died.

Secondly, it’s worth noting that “Channel Islands” is a geographical term, not a political unit: the islands are divided into two “Bailiwicks”, each with their own laws and political structures. The term also doesn’t refer to all the islands in the Channel, or even all of those in the archipelago off the Cotentin Peninsula: the southernmost Chausey islands, not quite on the map above, are generally not classed as Channel Islands on the grounds they’re French, rather than British.

All of which begs the question of why the others are British. They’re much closer to France, after all – Alderney is only a few miles off the coast.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.