Some numbers and some history to explain why the union is stuffed

One of those thoughts-too-long-for-a-tweet I sometimes have.

Google can be terribly cruel. If you ask it for a quantity that can be presented as a graph to show change over time, it will often provide one, unbidden, including extra data it thinks you might like to compare it to. I was searching for the population of Scotland, for reasons we’ll come to below, and the graph Google generated also showed me the populations of Wales and... London. Not England, you note, merely its capital. Look.

The reason for this, I imagine, is that including England too would render the graph unreadable. And this, conveniently, goes straight to the heart of today’s sermon.

We all know, I think, that of the four nations of the UK England is quite a bit bigger than the others. But I don’t think we always grasp quite how much bigger: so much so that the population of the other three combined is only slightly bigger than London on some measures, and actually slightly smaller on others. The union is out of balance, and we are now seeing the effects.

The union has always been out of balance, of course – England has the most land, the most good growing land, the most temperate climate, and the best connections to the continent. By all rights, you’d expect it to be the most populated, and so far as we can tell it always has been.

But its dominance has grown noticeably greater over time. Go back to the year 1500, and England had about 4.5 times as many people as Scotland, about eight times as many people as Wales, and not quite three times as many as the two others combined. It was bigger, but not overwhelmingly so.

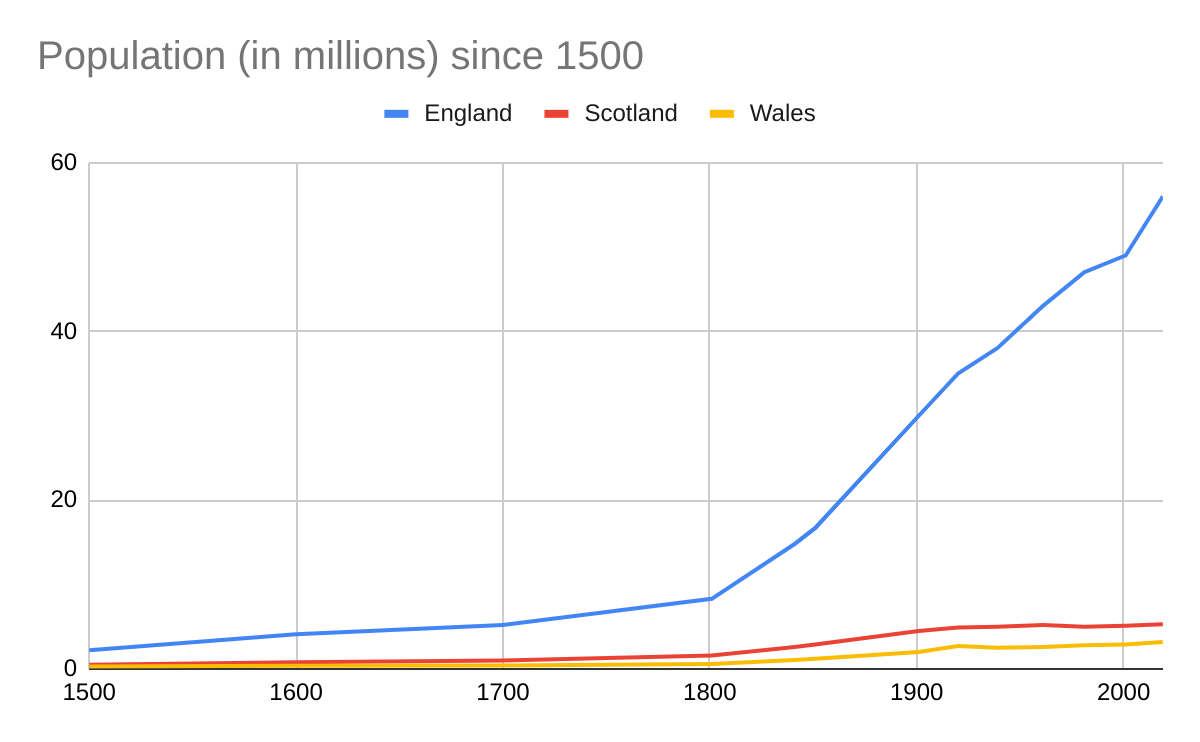

Already by 1707, the year of the Act of Union with Scotland, England was starting to pull away (five times the size of Scotland, 11 times that of Wales, slightly over three times the two combined). But it was after 1800, when the industrial revolution kicked in, that it really started zooming out ahead. Here’s a graph:

Today, England has roughly 10.5 times the population of Scotland, 17.5 times that of Wales, and 6.5 times that of the two combined. It’s not just bigger. It’s an order of magnitude bigger.

Here’s another way of conceptualising quite how out of balance the different bits of the union have become. Today’s England contains nearly 85% of the UK’s population, more than ten times more than any of the UK’s other countries. So far as I can tell, no other major union of smaller units is so completely dominated by its largest member.

A couple of years ago, on a whim – possibly triggered by some viral map or another, possibly the result of a West Wing box set and a fever – I decided to work out which of the UK’s countries were the closest equivalent to which US states in population terms. Scotland, with 8.2% of people in the UK, was the closest match for Texas, with 8.7% of the US. This was pleasing because both are oil-rich places that keep threatening to leave. By the same logic, Wales (4.7%) was the best match for Pennsylvania (4.1%), and Northern Ireland for New Jersey (both 2.8%). All three of these comparators are big, important states, two of which are electorally important: no constituent country in the UK is the equivalent of, say, Wyoming.

But there is no state that comes even close to the dominance of England. The largest, by population, is California, on not quite 12% of the US. England, remember, is 84.3% of the UK: it is California, plus the other 46 states we haven’t even mentioned, combined. Even if you only count the largest states, to get to 84.3% of the US population, you could include 26 of them – more than half – and you’d still be 700,000 people short, and need to throw in Alaska or DC to plug the gap. (This, by the way, would get you 372 votes in the electoral college. Nobody has managed that since Bill Clinton.)

Okay, there are 50 US states, plus a few tiny non-state territories, as opposed to just four countries in the UK: the comparison is not entirely fair. So let’s try a country closer to home.

For example, Germany. Scotland (8.2%) is the closest match for Hesse (7.6%), the 5th largest of Germany’s 16 states. By the same logic, Wales (4.7%) is the best match for Saxony (4.9%, ranked 7th); Northern Ireland (2.8%) for Saxony-Anhalt (2.8%, 11th; the fact that, with only 16 states to name, Germany chose to call three of them “Saxony” is a problem for another day).

That leaves the 13 others combined to be equivalent to England. The largest German state, by the way, is North Rhine-Westphalia. It contains around 21.6% of the German population, making it around 1/4 of an England.

You can play this game with pretty much any country made up of smaller units, and get similar sorts of results.

The largest Italian region by population is Lombardy. It contains just 16.67% of the national population.

By far the largest Australian states are New South Wales and Victoria, home to Sydney and Melbourne respectively. The former contains around 32% of the Australian population, the latter 26%. They don’t get close to England between them.

Canada contains 10 provinces and three territories. The largest by population is Ontario, at 38.3% of the lot. Its position is, compared to California’s within the US (remember: 12%), dominant. It still isn’t close to England.

I’m open to the possibility I am wrong about this – if I am, please tell me – but I don’t think there is another union anywhere in the world, in which one sub-national unit contains over four-fifths of the population. (UPDATE, MAY 2022: Someone did tell me. See note 2 below.)

This, I think, is the problem. Both history and decorum require a polite fiction that this is a union of equals (at least between England and Scotland: the other two aren’t granted the same treatment, that I can see). When Scots complain that they were dragged out of the European Union against their will, or that their entire country gets less attention than a single large English city, it isn’t just Nats whose sense of fairness is offended.

But should it be? Is it unfair, really? London has more people than Scotland, and the number of people affected by, say, a major transport scheme here is greater still. Of course it gets more attention. And there were eight times as many Remain voters in England as in Scotland: weren’t they too dragged out of the EU against their will, too? Do Scottish Remainers really matter more, just because they have their own flag?

Put bluntly: I’m not sure how the hell you manage a union of four parts of such radically different sizes. Allow England to dominate, and it feels unfair to the other nations. Don’t allow it to dominate, and it feels unfair to the people of England.

Is it any wonder, then, that the union has been on the skids for decades now – ever since, essentially, the UK stopped having a national mission to beat the Nazis/plunder the rest of the planet? Pretending the UK was a single unitary state didn’t lead to stability and unity. Devolution, which has allowed entirely different political cultures to grow up in different parts of the union, hasn’t done so either.

If the union does break up, as it seems more than plausible it will, this government, this Prime Minister, and the faction of the Tory party he has weaponised will all share in the blame. But, just occasionally, I wonder if that’s a bit unfair too. Perhaps the true culprit is simple maths.

Offcuts and sidebars

1. You’ll notice I excluded Ireland from the historic bit of my analysis. That’s mostly just because it turns a clear story into a messy one, in which I have to work out what to do about the famine of the 1840s (after which the population collapses) and partial independence from the 1920s (after which it’s not clear who, exactly, we should count), without illuminating very much.

For the record, though: in 1841, the population of Ireland was 8.2 million, more than three times that of Scotland, and over half that of England. Then the potato blight came. There are still fewer people living on the island of Ireland than there were in 1841.

Over the same period, the population of Great Britain has more than tripled. As with the sheer enormity of England, I think we all know the Potato Famine was bad, I’m not sure we always understand how bad.

2. I’m writing this from May 2022, by which time I’ve re-promoted this piece a few times. Two more examples people have suggested to me on Twitter:

a) The USSR is not a counter example. In 1989, Russia contained 51.4% of the country’s population. But…

b) …Trinidad & Tobago is. The latter island contains less than 5% of the state’s population. So, there you go. Thanks to Mr Grumpy, who despite being an anonymous Twitter account has made a really good point.

3. When I first looked at this theme for the New Statesman’s May 2015 site nearly seven years ago now, I noted that:

Perhaps the multi-state entity most famous for being dominated by a single one of its members was the German Empire, which lasted from 1871 to 1919. At its creation in 1871, its dominant state, Prussia, contained around 25m of its 40m people. That’s around 62 per cent of the total. In other words, England dominates the UK more – far, far more – than Prussia dominated the German empire.

And, I could have added: look what happened to that.

I also noted that:

Oh, and [England is] the fastest growing bit of the UK, too, so this problem is going to get worse.

Since September 2014, when I wrote those words, it has.

Housekeeping and self-promotion

1. This is a free post. If you enjoyed it and you want to upgrade to the full Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything service, so that you get some politics, some nerdery and a map delivered to your inbox every Wednesday afternoon at 4pm, you can become a paying subscriber here:

Alternatively, if you’re already a subscriber, but you’d like to ruin someone else’s Wednesday:

2. It is now under two months until my first book, The Compendium of (Not Quite) Everything, sees the light of day. The cover is a thing of beauty, look:

Want to pre-order? You can do so via Waterstones, Amazon or Foyles.

3. Related to that, there will be a podcast. No link to that, as of yet, but I’ve recorded my first interview with somebody awesome, and trust me, it’s going to be great. Watch this space.

I'm going to be cheeky and post a link to an article I wrote about this - https://itcouldbesaid.substack.com/p/it-could-be-said-8-how-do-you-solve. I think the size of England is absolutely an issue, but the traditional solution is the right one - encourage England to express its patriotism through a British framework that encourages it to be generous to its neighbours

I would suggest that people tend to following where investment is creating jobs and therefor major projects like HS2 which have a dis-benefit to Wales will likely see population increase outside of London but still a greater pull towards England and away from Wales. Investment into Wales under this UK government seems dependent on it also benefiting English regions on the border but that doesn't solve any part of the problem.

I wonder what your thoughts are on Mark Drakeford's 20 step plan to save the Union? I know it's difficult to find because only the Spectator and Guardian reported on it but could be an interesting follow up to this piece.