Spot the Difference

This week: some thankful villages; some countries which have changed their names. But first: some thoughts on why we keep misreading election results.

I am, of course, a hypocrite. Last Friday, I posted a numbered list to BlueSky:

1. When prices go up, incumbents go down;

2. A small but electorally significant number of Americans won’t vote for a female president;

3. A lot of voters pay little attention to politics and thus weren’t really aware of/don’t believe the bad stuff.

“There are going to be a lot of words attempting to explain this election,” I added, “on Trump’s strange electoral appeal, what the Dems did wrong, whose fault it is – but my gut instinct is that those three things are probably enough to explain a lot of this.” To put it another way: here were some more words attempting to explain this election. But they are my words, which are good, as opposed to other people’s, which are bad. Like I said: a hypocrite.

I do, as it happens, stand by all this. Women have made it to the presidential ticket of a major American party in five elections: twice as candidate for president (2016, 2024), thrice as VP (1984, 2008, 2020). In each of those, the party that made that choice underperformed expectations. I don’t like this any more than you do, but I think we have to consider it as a factor.

Then again, price rises have seen incumbent governments turfed out of office all over the globe in 2024, and even those parties with a lock on power (Japan’s Liberal Democrats, India’s BJP, South Africa’s ANC) have lost ground. In the words of University of Washington political scientist Victor Menaldo, “inflation is radioactive”.

But the biggest, and hardest to internalise, factor may be the third on my list: most people simply don’t care about politics. They thus weren’t listening to what candidates or commentators said. And when they voted, they didn’t think about January 6th or Puerto Rico or tariffs or deportations or, god help us, Elon Musk. They thought, instead, about the fact their grocery and gas bills had gone up, and that they were happier in 2020, and they voted accordingly.

The right likes to say the left is out of touch; the left likes to get defensive about it. But the truth is that, by having a strong political view in any direction, you are by definition unusual. There’s an upsettingly strong case that, the more you think about politics, the less you will understand the electorate.

We may all be prone to over-interpreting this stuff anyway, because this was not, in the end, a landslide, in popular vote terms. (Let’s ignore the electoral college, just this once.) The votes are still being counted, but it looks like the difference will be around 2 percentage points: in other words, had just over 1% of the electorate switched from Trump to Harris, she would have won more votes than him. Our instinct is always to go in search of Grand Unified Theories of election results, when the more prosaic truth is there are probably loads of things that could have swung that many people.

So, yes, I do think the factors I listed are key. But if we’re looking for explanations that could have shifted 1% of the electorate? Well, maybe Joe Biden’s refusal to drop out until pushed, and the lack of a Democratic primary, are in there. Maybe Harris’ race is. (I don’t like this one either.) Or her weakness as a candidate, for reasons that have nothing to do with gender or race. Or the fact she didn’t do The Joe Rogan Show. Or the fact she did do Saturday Night Live. Or Gaza! Or Ukraine!

We do this dance with every close election. Did George Osborne’s 2016 Budget lose the Brexit referendum for Remain? Did Jeremy Corbyn, through his lack of enthusiasm? Did Boris Johnson? Any and all of these seem like things which could plausibly have swung the 2% of the electorate necessary to flip the result. Perhaps in another universe, we’d be talking about how Corbyn’s passionate defence of Brussels saved Britain’s EU membership – or are, even now, discussing the vital role pro-choice women played in an election in which 98 voters in 100 voted in the exact same way they did in this universe.

My point is not that these things aren’t factors: it’s that they aren’t the reason for an election result. People vote for a million different reasons, and all sorts of things might be the one that pushes one candidate rather than another over the top.

But we shouldn’t mistake “Why did Harris lose” for “Why did Trump win”. The fact he won the last couple of percentage points necessary to take victory seems, to me, rather less alarming than the fact he won the first 48, too.

The book bit

A “smorgasbord of geographical history.... I can’t wait to devour more”. Here’s a lovely review of 47 Borders on Geek Dad, a website I wasn’t really familiar with, but where I suspect the vast majority of my potential American readers reside

If you have a geek dad in YOUR life, then why not come to Foyles on 28 November, when myself, my mate Miranda Sawyer and a load of other authors will be signing books and looking awkward in the presence of mince pies? The book, as ever, is available from Waterstones, Foyles, Amazon or my American publisher, The Experiment.

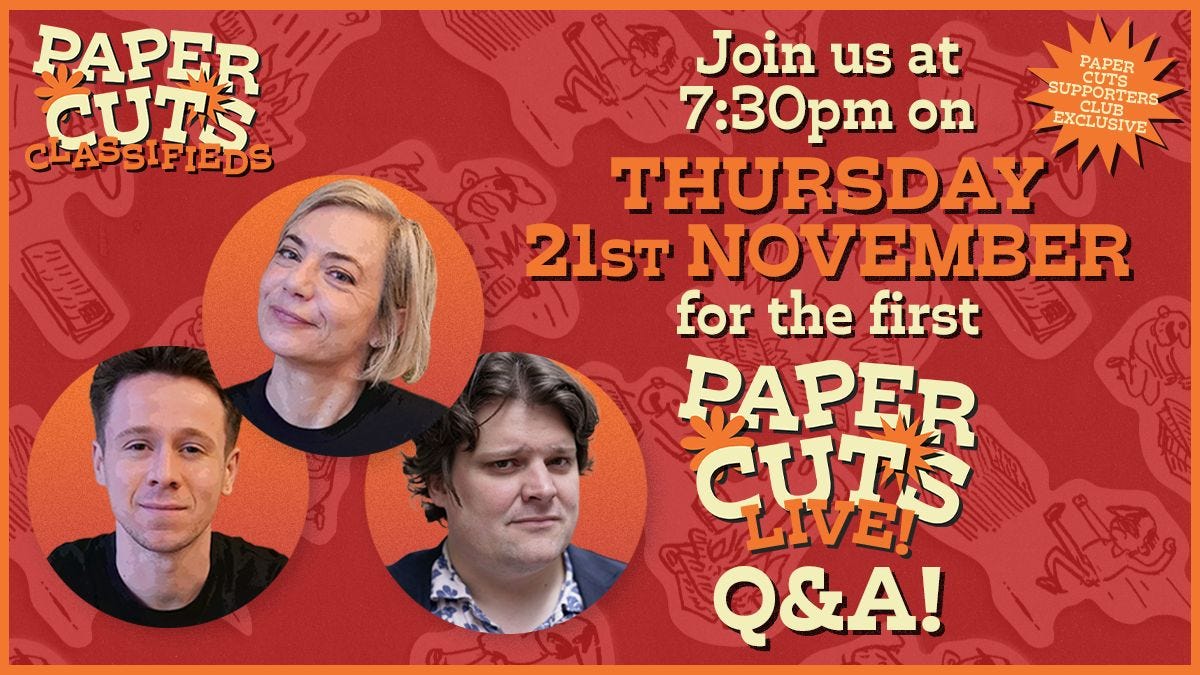

Oh, talking of Miranda, though, why not join us next week for a Paper Cuts livestream? (Paying supporters only, but, there’s a fix for that.)

Some countries which have tried to change their names

A few weeks ago now, a long-time reader and social media mutual told me that they were disappointed to see me effectively dead-naming an entire country by referring to “Turkey” throughout my book. I responded by arguing that this was the standard English name, that using “Türkiye” would be just as weird as referring to Germany as Deutschland or going round pointedly calling it Fronce, and was feeling all pleased with myself when someone else popped up to point out that Türkiye had officially changed its name in 2022, and it’s just that I hadn’t noticed.

Oh well. It’s all content isn’t it? Let’s talk about some countries that changed their name.

Myanmar

The government of the country historically known as Burma announced it would henceforth be known as Myanmar back in 1989. The former is a British colonial name, imposed by outsiders; the latter the country’s name for itself. Simple, right?

Well, no, there are a couple of complicating factors. Firstly, it turns out that Myanmar and Burma are, unexpectedly, the same name: the Burmese language has very different vocabulary for different registers, and Myanmar is the formal, written version for the more colloquial Burma. Inside the country, the rebrand changed nothing.

Secondly, that rebrand came a year after the military government attempted to suppress a pro-democracy uprising, making itself a pariah: that raises questions about whether it was quite as into freedom and self expression as it claimed, or whether the name change was a distraction. As a result, much of the world kept calling the country Burma for years as a way of supporting the opposition.

Czechia