There’s an oddly shaped war memorial in Bethnal Green Gardens, the park next to my local tube station. It looks like an upside down staircase, made of what I’m assuming is wood but looks to be brick; inscribed on it are surnames. Aarons, Asser, Bailey, Baker.

I’ve passed this structure a dozen times a week for five years now, and rarely given it a second thought. War memorials, after all, are ten a penny in this country: every community has one, sometimes several. On one, in King’s Cross Station, I once spotted something unnervingly close to my own name – J. R. Ellege, my initials on a surname very nearly my own – and, having watched too much dreadful sci-fi involving time travel, this did some pretty bad things to my brain.

The Bethnal Green memorial, though, turns out not to be the usual list of the war dead. It commemorates a specific disaster which happened over 80 years ago. The dead it names are not soldiers, but civilians. And it wasn’t a German air raid that killed them.

The eastern extension of the Central Line was still under construction when the war broke out – passenger services would not begin until 1946 – but that didn’t mean it wasn’t already useful. This was a densely populated bit of the East End, after all, and lying near to both docks and City it was bombed fairly heavily. So a new, deep level tube line, bored deep into the ground beneath London, provided local families with somewhere apparently safe to shelter while the bombs started falling. Without interruption by trains, the new tunnels could hold thousands.

By 3 March 1943, with the war over three years old, all this must have begun to feel almost routine – so when the sirens began to sound just after 8.15pm, over a thousand eastenders made their way to the tube station as normal. That night, though, something was different. Firstly, for some reason, only a single entrance to the half-finished station was open – no staff seemed to be on duty – forcing everyone to enter down the same narrow stairway. Secondly, a few minutes after the sirens began, there was an unfamiliar sound in the air: as loud and terrifying as the bombs, but which arrived long before the planes could be heard.

No one in the crowd trying to get into the tube station knew what could make such a sound; and so, they panicked, as crowds are wont to do, and surged forward. Towards the bottom of the stairs, a woman holding a child lost her footing, pulling an elderly man down with her. More people, apparently propelled by the momentum of the crowd, fell on top; those behind, unable to see what was causing the blockage, kept pushing forward. More and more bodies were crammed into a space that could not contain them.

It was nearly midnight before the last casualties were brought out and laid on the pavement. Those who witnessed it later told stories of bodies turned purple by asphyxiation, of children identified by their clothes because they’d been left so unrecognisable by the crush. In his account for Historic UK, Brian Penn – whose 16 year old mother lived a few minutes’ walk from the tube station, and whose grandfather had luckily decided it was a false alarm that night – tells that they included his uncle George, who’d returned on leave that very day, excited to see his wife Lottie and three year old son Alan for the first time in months. On being told that they’d gone to shelter from the air raid, he rushed to follow them down the tube. None of them made it out again.

In all, 173 people died in the crush, 62 of them children – the worst civilian disaster to take place in Britain during World War Two, and the single greatest loss of life in the tube, all at the same time. But there were no bombs that night. The noise was not that of a terrifying new German weapon that could arrive without warning, though those would be landing soon enough. It was the sound of new anti-aircraft guns being tested up the road in Victoria Park.

This fact, that it was the actions of the British military which sparked the panic that caused the disaster was something that led the government to cover up the disaster for decades. Its reason for doing so, it claimed, was to protect morale. But reading accounts like Penn’s, and that of Joan Martin – a doctor who handled the bodies that arrived after the disaster, and whose inability to discuss what she’d seen gave her nightmares for decades – I can’t help but wonder if that was the only thing that decision was meant to protect.

Anyway. The memorial was unveiled in December 2017, and it is quite genuinely rather beautiful; even more so, once you realise what it’s for. If you find yourself in the East End, it’s worth checking out. I can recommend a pub if you find you need a drink afterwards.

Map of the week

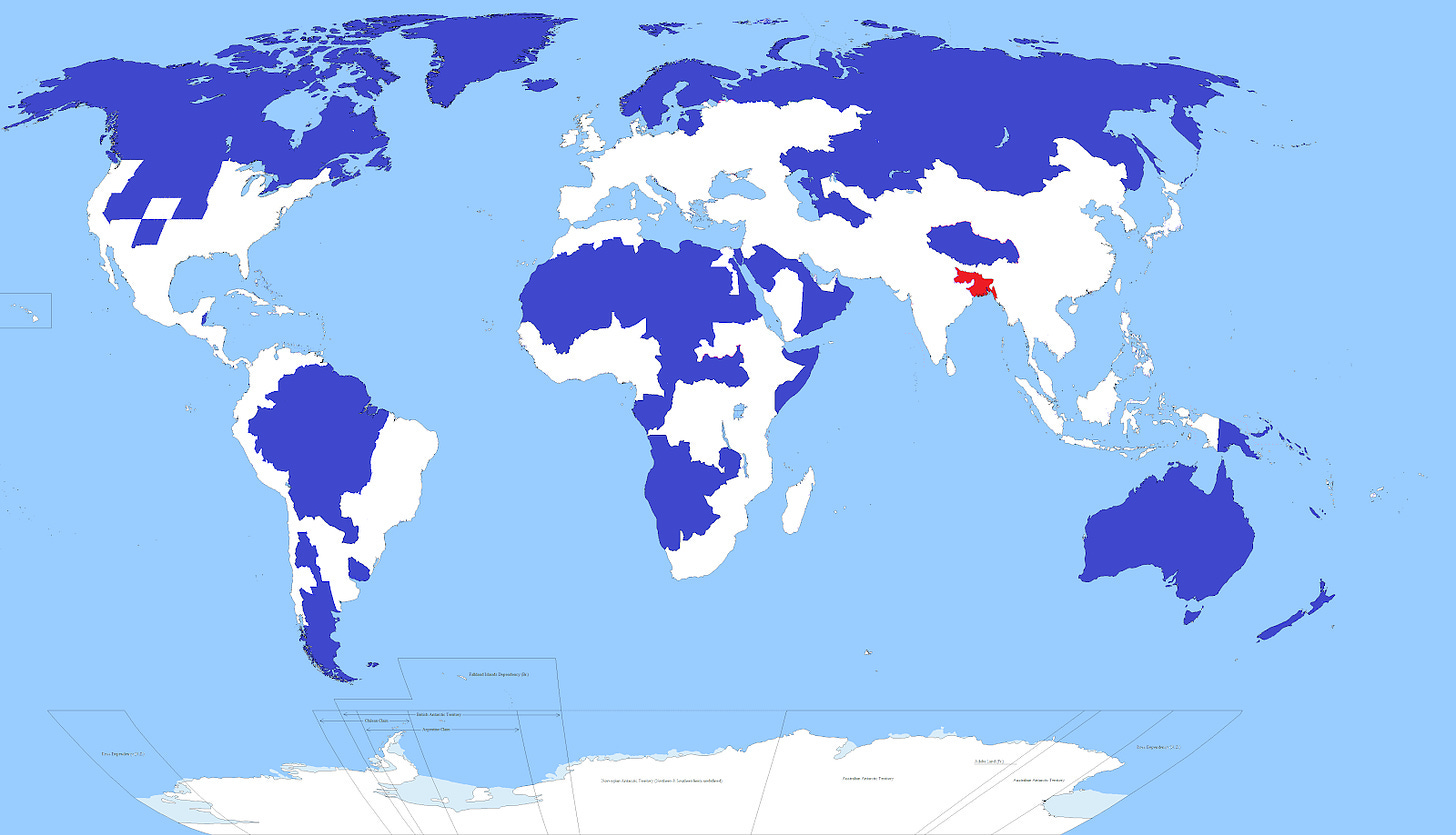

This week’s entry has been doing the rounds on the internet for so long that who originally made it seems to be lost to history – the earliest version I can find is this one on r/mapporn, where it appeared back in 2015 thanks to Ibis Digital Media, an, erm, small wedding video production company based in Dallas – but we can take an educated guess as to how its creator did it. Find an incredibly densely populated area, check how many people live there, then work your way down the list of incredibly sparsely populated areas adding their populations up, until you get roughly the same number.

Result: this map, and the unrestrained joy that comes from when something you’ve created goes viral (for a good reason, I mean).

Around 5% of the world’s population – some 350m people – live in the area shaded red. Roughly the same percentage live in the area shaded blue. Wowsers.

The map, alas, doesn’t come with a key. But the blue area seems to include all of Canada, Mongolia, Scandinavia, and the Baltics; pretty much all of Australasia; huge chunks of Africa and the Arab peninsula; most of northern and Asian Russia; the US states of New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Kansas, Nebraska, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, and both Dakotas; and probably some other bits that I’ve missed. (It doesn’t include Antarctica, though it obviously could.) Much of the territory here is desert, tundra, steppe or otherwise not massively conducive to a large and settled population.

The red area includes Bangladesh (pop. 163 million), and just two Indian states, Bihar (pop. 104 million) and West Bengal (pop. 91 million).

The population of the UK, by way of comparison, is around 67 million. That is a lot of people squeezed into not a lot of space.

I don’t want to scare the crap out of anyone, but it feels worth noting at least in passing that the Ganges Delta, which makes up much of this area, is quite vulnerable to the sea level rises that might be brought by climate change. It’s going to be a long century.

The other bit

So, two things:

1) My new book is published two months tomorrow Here’s another lovely quote, this time from Phil Tineline, author of The Death of Consensus: “Jonn Elledge is a wonderfully lively writer, because he has that knack of being warm, funny and sharply political, all at once. This makes him the perfect guide for a survey of world’s borders. Under his quizzical gaze, those lines you've never really thought about are revealed as deadly serious, and utterly absurd.”. As you probably know, because I never shut up about it, pre-orders really help with visibility later on so please, you know what to do

2) If you’d like to read stuff like the above when I write it, rather than when I deign to release it from the paywall and sometimes not even then, my rates are very reasonable. For just £4 a month, or £40 a year, you can get a weekly dose of politics, maps and nerdery like the above, plus some diverting links.

At the moment, because I keep forgetting to switch it off, you can have 30% off if you sign up for a year.

Alternatively, as ever, if you want to read the newsletter but for whatever reason can’t justify the money right now, just hit reply and ask. I always say yes. Really.