Well, there’s your problem

Even before Kwasi Kwarteng accidentally pressed the self-destruct button, “Tory economic competence” was an increasingly implausible myth.

There are a couple of graphs that we’ve all, in the literal days since Liz Truss became Prime Minister, grown regrettably familiar with. One shows the value of the pound against the dollar. That one points downwards, which is bad. Another shows the interest rates the bond market is demanding on UK government debt, known as “gilts”. That one points upwards, which is also bad.

Both Truss and her chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, are getting a lot of stick for this, which is not surprising, since essentially the first thing they did on entering office was to cut taxes for the rich while making things worse for the rest of us, thus spooking the markets and triggering an entirely self-inflicted financial crisis. This is extremely bad.

But, here’s the thing: we were not in a great state anyway, even before this downgrade in expectations. And five seconds with almost any graph of Britain’s recent economic performance is enough to prove it.

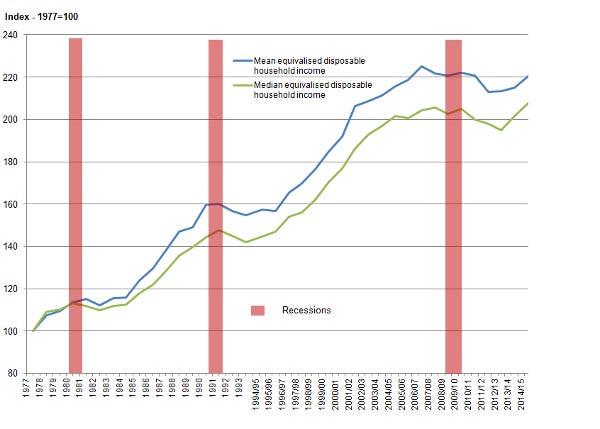

By way of example, consider this, from the Office for National Statistics, which shows how average disposable incomes have changed since 1977.

After the recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s, incomes soon resumed their upward growth. After the financial crisis of the late 2000s, they did not, and have basically flatlined ever since. That graph only runs up to 2014-15. This version from EconomicsHelp.org shows that things have not improved.

Here’s another chart, this one from the Resolution Foundation, showing wages across western Europe. Britain was hit hardest by the crash – I’m guessing because it had the largest financial sector – and has struggled to recover since.

Suggested Tory campaign slogan: “Only slightly worse than France!”

Things get even worse when you break the country down into smaller components. Here’s my own graph of ONS figures for regional GVA per capita, a measure of productivity which correlates pretty closely with wages. I haven’t labelled the regions, because with 11 of them to contend with it made the graph messy and the exact details don’t matter: all that does is that you know that London is a region in itself, because I bet you can tell which one it is.

The next one down, incidentally, is the “South East”, which includes about two-thirds of the Home Counties.

While we’re talking regionally, here, courtesy of Eurostat, is a map of Europe showing productivity in 2017. Regions in blue are above the continent’s average productivity rate; regions in red are below it. Compare Britain to the countries we think of as our peers.

I don’t think these problems can be blamed entirely on the Conservative party. The collapse in income and productivity dates to the crash, and while that was not Labour’s fault, it still happened on Labour’s watch: what happened next suggests that problems with our economic model predate David Cameron’s arrival in Downing Street in 2010. (My guess, having read Will Hutton’s The State We’re In at a formative age, is that they actually go back a lot further than that.)

What’s more, it’s not a completely British problem: as noted above, France, which as another fairly large western European country with an over-mighty city at its heart has an economy that looks at least a bit like our own, has also struggled; this chart from Our World In Data shows growth in GDP per capita has been sluggish right across western Europe for a decade. (Partial exceptions: Germany, which did better in the immediate rebound from the crash, possibly because Eurozone interest rates are largely set for its benefit; and Ireland, which has just done better across the board.) There are clearly factors that do not relate to the decisions made by Tory Chancellors.

Nonetheless: this government has been in office for 12 years. And the result of all its hard work is an economy that has still not rebounded from the crash and flatlining wages. More than that, cuts have made everything about this country – from the collapse in local bus or library services, to the physical state of our parks and streets, to, most unnervingly of all, your chances of getting an ambulance when you need one – very visibly worse. And they have done so, without actually reducing the national debt, which, we were told, was the entire bloody point of the entire bloody exercise:

That’s without even getting into things like home ownership being harder to attain. Or young people today graduating with student debts (theoretically)/effective tax rates (in practice) vastly higher than their parents’ generation. Or the collapse in the value of a British passport too, which means that the main thing protecting us from a national brain drain is the fact it’s now so difficult to leave.

At any rate, when the leaders of Britain’s government say that what Britain really needs is growth, their diagnosis is quite correct. It’s just that their treatment – gutting government investment yet further, to fund tax cuts for people who don’t need and won’t spend the money – is like treating a sprained ankle by cutting off your leg. More than that, talk of a “growth plan” risks raising questions about the fact we haven’t had any growth recently. A dozen years into this government, it shows the Tories’ reputation for economic competence to be the myth it always was.

This is the message that Labour should be hammering remorselessly. Twelve years into the last Conservative government, industries and regions had been laid waste, but other areas had clearly boomed. Twelve years into the last Labour one, the crash had come, but the country was looking better than it had in 1997.

Twelve years into this Conservative government, though, the country is visibly and demonstrably much, much worse than it was before they got here. And yet, the very first thing the Truss government did was to cut taxes for the rich and send interest rates spiking for the rest of us. The second thing it’ll do is cut spending. Again.

In 2010, the Conservative party came to power, asking us to make sacrifices to help them fix “Broken Britain”. That was twelve and a half years ago. Britain is still broken – and they haven’t stopped asking yet.

Look, who are you and why are you in my inbox?

The article above is an expanded extract from the archive of the Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything, a weekly newsletter which goes out every Wednesday at 4pm. Sign up, and for just £4 a month or £40 a year you’ll start receiving it this week, plus be able to read all the stuff I never take out from behind the paywall, too.

That said, as I may have noted already in this email, times are tough. If you can’t currently justify paying for some nerd’s substack (unemployed, underemployed, impoverished student, and so forth), just hit reply and I’ll give you a complimentary subscription, no questions asked.

Or here are two things you can read completely free:

“If one emperor didn’t deliver, they would simply kill him and appoint another. If he couldn’t deliver either – well, you get the point.” My latest New Statesman weekend column, on the addictive nature of regicide;

A lot of nonsense I’ve written about Doctor Who, which you can find here.