Welcome to the latest fortnightly digest of some previously paywalled stuff from the archive. This week, two pieces from last year concerning the shape and movements of the Earth.

As ever, if you’d like to get this stuff as it comes out, and read all the other stuff that never escapes the paywall too, you can become a paying subscriber here:

Seasons lag. This is why

One Monday last September, it was warm, but over-cast: depressingly standard London summer weather. The previous week we’d been in the middle of a full on heatwave; a few days later, it was chilly and chucking it down. Those, too, are perfectly normal summer weather in our miserable climate.

But it wasn’t summer: the schools had gone back, the holiday season was over, the nights were drawing in, and autumn was here. By common consensus, summer had finished two weeks ago. Yet the weather seemed to disagree.

Half a year on, and it’s at it again. A few weeks ago, there was blazing sunshine and the weather was too warm for all but the lightest of jackets. A few days ago, it unexpectedly started to snow. “Spring”. Sure.

This is not, for once, a symptom of the fact our species has been gleefully destroying its planet for two hundred years or more, but a fairly reliable phenomenon. September is often warm, yet every year we’re surprised. We’re not surprised when the harshest bit of the winter comes more than a month after Christmas, but it is, when you think about it, basically the same phenomenon. The thing we think of as the mid-winter festival is more likely to mark the start of winter than the moment we’ve made it half way through.

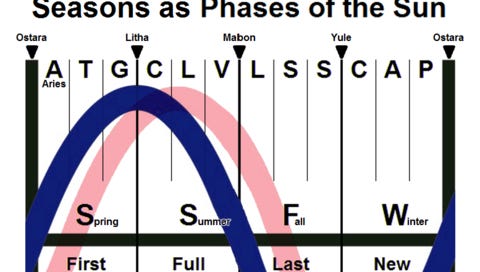

There is, it turns out, a name for this phenomenon: seasonal lag. The hottest bit of the summer generally comes around a month after the summer solstice; the coldest part of the winter some time after the winter one. Here’s a helpful graph which, because I found it on Wikipedia, comes with neo-pagan labelling. The blue line marks the amount of light you can expect at a given latitude in the Northern Hemisphere; the pink one the amount of heat. If you’re in the Southern Hemisphere, you just need to turn it upside down.

Image: Invent2HelpAll/Wikipedia.

The reason why this happens is that the amount of daylight is not the only factor contributing to ambient temperature: how warm the environment already is plays a part, too. This is also why a summer day will generally be hottest not at noon, but a few hours afterwards, a phenomenon known as diurnal temperature variation: it isn’t just the sunlight, but the amount of heat already around.

That said, some environments are better at retaining heat than others. In oceanic areas, the hottest point of the summer tends to lag by more than in continental ones, because water is better at retaining heat than land. The result is that the warmest time of the year in San Francisco, for example, doesn’t hit until September; in Denver, though, a thousand miles from the ocean, the warmest month is July. Oddly enough, though, the lag isn’t always symmetric: indeed, in San Francisco, the coldest month is December, meaning there isn’t a lag at all.

All this, at least, explains why the autumnal equinox (or mabon, to the neo-pagans) tends to be warmer than the vernal one (ostara), even though both receive equal daylight: September is a month of heat lingering on from the summer, while March follows the coldest part of the year.

Seasonal lag cannot, alas, explain why exam season is often glorious, yet the summer holidays are wet and gloomy. For that, I fear, we only have the weird English climate and its desire to torture students to blame.

Map of the week

The shortest path between any two points on the globe follows a great circle. There’s a lot of slightly upsetting trigonometry involved in calculating this, but what it essentially means is that, if you draw the biggest circle you can taking in your start point and destination – a circle the size of the entire circumference of the planet, with the centre of the Earth at its very centre – you will find that the shorter of the two routes between those points that this circle plots is the shortest possible distance between them.

If you think that sounds counter-intuitive, just you wait until you see the routes it generates. Look at any standard map projection, and you might imagine that the shortest path from London to Sydney would involve heading roughly south east, perhaps flying over the Adriatic, Arabian Peninsula and southern India. In fact, though, the most direct route from London to Sydney initially involves flying east north east over southern Scandinavia. You could stop off in Moscow on the way.

Image: Great Circle Mapper.

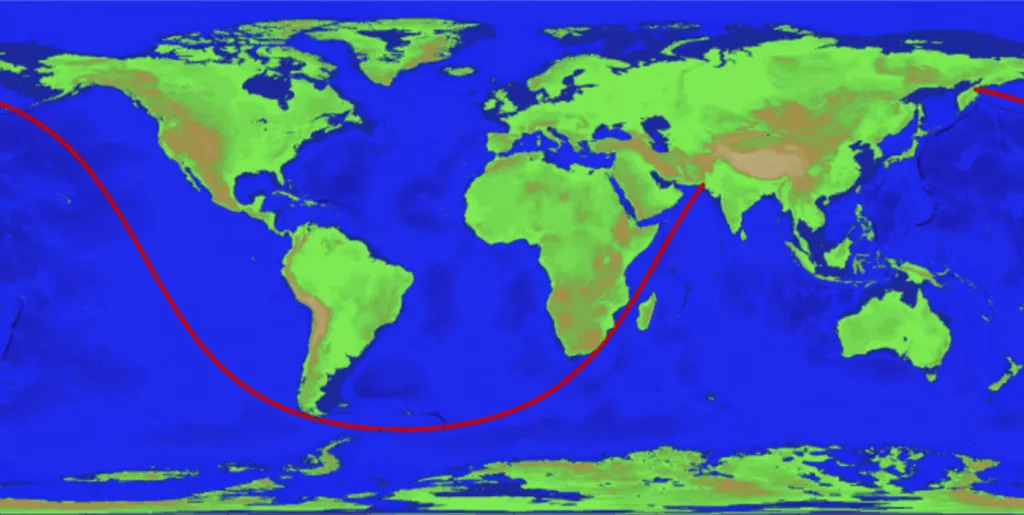

All this is an incredibly long run up to explain why the longest distance you could sail in a straight line without hitting land doesn’t look like a straight line at all.

Rohan Chabukswar and Kushal Mukherjee, a pair of researchers at the United Technologies Research Center in Cork, plotted the route in 2018 in response to a question posed by Live Science. They worked out that, if you set off from the coast of Pakistan, it would be possible to sail for nearly 20,000 miles – between Africa and Madagascar, narrowly missing the coast of South America – before hitting land again in the far north east of Russia.

And although it looks like a curve on a two-dimensional map, your theoretical boat would actually be sailing in a completely straight line.

Image: Chabukswar & Mukherjee, via Live Science

Amazing things, globes. You can read more from Live Science here.

This is an extract from the (paywalled) archive of the Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything. As you may or may not have noticed, I send one of these out to the free list roughly once a fortnight.

If you want to get all of this stuff as I write it, instead of several months after the event, and want to read the other roughly 80% of the newsletter I never take out from behind the paywall, why not become a paying subscriber? For just £4 a month, or £40 a year, you’ll get a newsletter containing several of them every Wednesday. Hey, I’ll even throw in your first month free. Just click this link or press the button below.

Can’t currently justify paying for some nerd’s substack (unemployed, underemployed, impoverished student, and so forth)? Just email me, and I’ll give you a complimentary subscription, no questions asked.