A History of Conspiracy Theories, With Jokes

This week: nine key dates in the history of conspiracism. Plus, YouGov has been asking Londoners stupid questions about the Tube again.

No news bit this week. There’s a lot happening – South Korea! Syria! The hot hitman! – but little I feel especially well-placed to comment on, and besides, today’s main feature is a bit of a monster. For what little it’s worth though: declaring martial law is bad, failing to declare it is good, overthrowing murderous dictators is good even if what follows might be bad and, last but not least, phwoar.

Anyway! Last June the Fortean Society asked me to give the “ease everyone into the day” session at a conference, by (I paraphrase, but not by much) summarising the entire history of conspiracy theories, with jokes. I rapidly decided that was a bit much – partly because it had taken Tom Phillips and I an entire book to do that and I only had half an hour, partly because Tom wrote all the clever bits, but mostly because it came right in the middle of the UK’s general election campaign and I was absolutely knackered.

What I came up with instead was a sort of listicle, in which I identified some of the key dates in the history of conspiracism, explained why they mattered, and then summarised some of the themes that emerged. What follows was inspired by that talk.1

October, 19CE

Germanicus Caesar was a very successful Roman general, and a plausible heir to the imperial throne then occupied by his uncle Tiberius. If you’ve ever seen I, Claudius, you may remember him as Derek Jacobi’s hunky older brother.

You will also remember, if you’ve ever seen that fine bit of BBC drama, or indeed read the Robert Graves novels it was based on, that heirs to the imperial throne had a habit of dying suspiciously often and suspiciously young. And so it proved with Germanicus, who became horribly ill while on campaign in Syria and died, aged just 33. It’s possible this was natural causes; it’s equally possible it was not. We’re never going to know.

The key thing for our purposes, though, is that it took him a month to die. That gave him time to accuse both the governor of Syria and his own uncle of poisoning him. You may or may not consider this paranoia – he genuinely was dying, and being the imperial heir was not a safe thing to be – but it does make Germanicus the source of the oldest conspiracy theory we could find. More than that: it gives him the rare honour of being one of the few people ever to spread conspiracy theories about his own death.

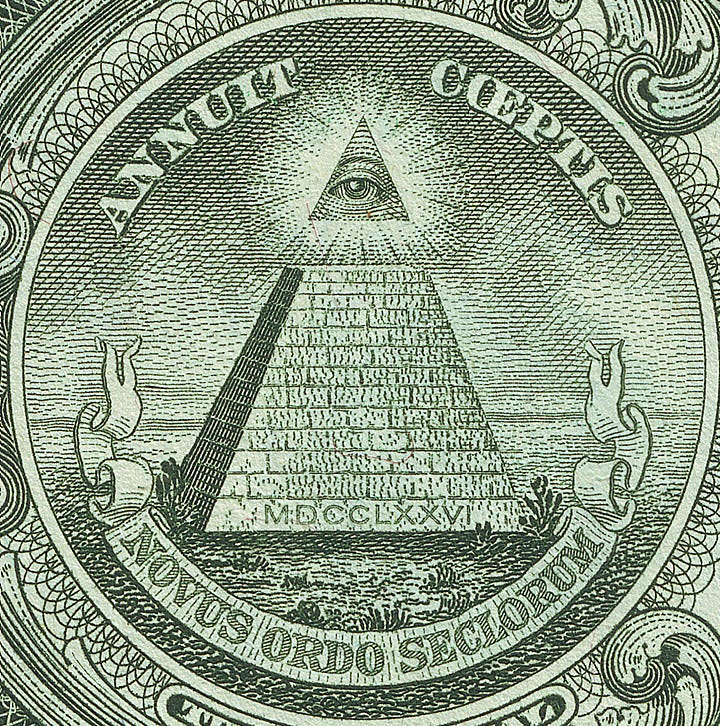

1776

You may notice we’ve jumped forward by quite a long way there. I could have stopped earlier, to talk about the anti-semitic blood libel, which has its origins in a specific conspiracy theory which sprang from Norwich in 1144; or possibly the Popish Plot of 1678, in which a man named Titus Oates went around claiming Catholics were trying to murder Charles II and take over the country, and which is notable mainly because one of the main people going around saying this was bullshit was, er, Charles II.

But one of the theories we put forward in the book was that, while the evolved impulses that drive this stuff have been with us forever, for conspiracism to become a serious political force you sort of need, well, politics. “There’s something they’re not telling you” is not a meaningful statement in a world dominated by church and crown, where there are loads of things the ruling class aren’t telling you and nobody would expect otherwise. To really bloom, conspiracism requires the Enlightenment.

The reason I’ve chosen 1776, though, is probably not the one you think: the foundation of the United States is a cute coincidence. The reason we’re stopping here is instead that this was the year when an Ingolstadt-based philosopher named Adam Weishaupt founded a secret society to push radical and sinister ideas like republicanism, secularism, liberalism and (most shocking of all, this) gender equality.

The Union of Perfectibilists was a little more than a Bavarian book group: it struggled to attract members, and when it did immediately fell to infighting because Weishaupt didn’t like them. The Bavarian authorities eventually tried to ban the thing, and it all collapsed in a sex scandal involving Weishaupt’s attempt to procure an abortion for his sister-in-law. The whole affair lasted less than 10 years.

The only reason it matters at all is because it wasn’t always known as the Union of Perfectibilists. You know it as the Illuminati. Yes, they existed; yes, they wanted to overthrow German society. No, they didn’t manage it, and no, they don’t exist any more.

So why have we all heard of them? Why do they get the blame for everything?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.