An Early Modern Way of Having Too Many Browser Tabs Open

Also: some maps, dropped on other maps.

Everything that follows originally went to paying subscribers in May. Yes, both bits. In the same email. Along with a furious screed about the state of the Labour government! Really, I do spoil my subscribers, so if you enjoy this email…

In his 1978 radio series The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams came up with the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: a device, roughly the size of a book, that would fit in your pocket yet contain an entire computerised and slightly sarcastic encyclopaedia. At the time, such technology felt incredible.

It took only a couple of decades for reality to surpass it. In your pocket, every day, you likely carry a device through which you can access, if not all the world’s books, then vastly more of them than you’re ever going to be able to read. If that doesn’t appeal, you can also use it to play music, watch films, talk to your nearest and dearest, start pointless fights with strangers, contribute to the rise of or fight against fascism, or enjoy this very newsletter. It’s quite, quite mad.

So it’s easy to forget just how recently that our access to information was limited not merely by availability or cost, but by the limitations of the physical world. It’s barely a generation since an entire encyclopaedia contained multiple heavy books that you couldn’t possibly hope to carry around. Even switching from volume to volume to compare entries would have been impractical.1

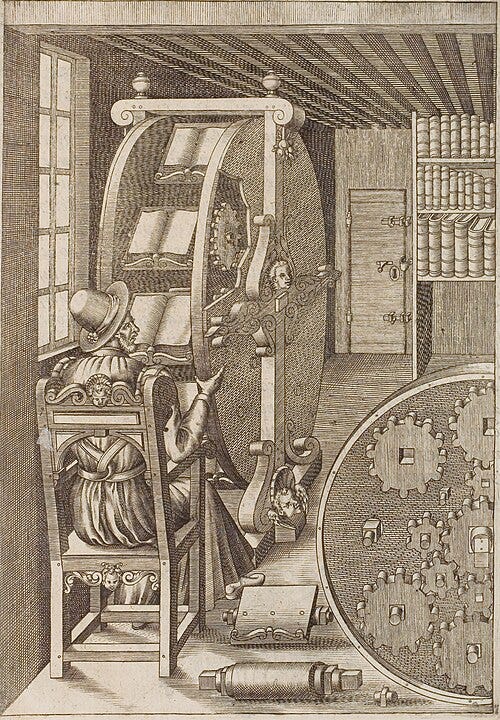

Unless, of course, you had one of these:

This is a book wheel, designed by the 16th century Italian military engineer Agostino Ramelli. At that time, books were so huge and heavy that even flicking from one to another was awkward if not physically exhausting. So in 1588 Ramelli proposed this device, which would allow the reader to keep as many as a dozen books open at the relevant page, and move between them by turning the wheel using their hand or foot. A system of “epicyclic gearing”, til then used mainly for astronomical clocks, would ensure the shelves remained at a standard 45 degrees and hold the books secure.

Actually, the gearing system (I think it’s a large cog at the centre, one for each shelf, and a set connecting them in between) may have been a little over engineered. As anyone who’s ever been on a ferris wheel can tell you, gravity will do a lot of that by itself. Ramelli also never seems to have built his bookwheel.

But many who came after him did: hundreds were built and used during the 17th and 18th centuries, and 14 are still thought to exist today. A few years ago academics and students at the University of Rochester, in upstate New York, also built two new ones, based on Ramelli’s designs.

I first learned about the bookwheel from my friend Matthew Symonds, a historian at UCL who specialises in such matters. (If you’ve read my own latest book, I can tell you that a lot of the United States of Greater Austria chapter was written in Matt’s living room, where I had gone to feed his cat.) So used am I to the idea that books are handheld that I couldn’t immediately get my head around why you would ever need one. I was also thrown by the way it’s described as a form of “reading technology”: why would you need technology just to read?

But then I thought about how much time I spend flicking between browser windows, to double source facts or pin down complicated things. It suddenly hit me how many connections I’d never have made if every time I wanted to do that I had to spend several minutes finding the right page in the right book, and laboriously flicking between that and other texts. The bookwheel is essentially an early modern web browser.

As for “reading technology” – well, we never think of the things that precede us as technological. Our forebears, though, might disagree.

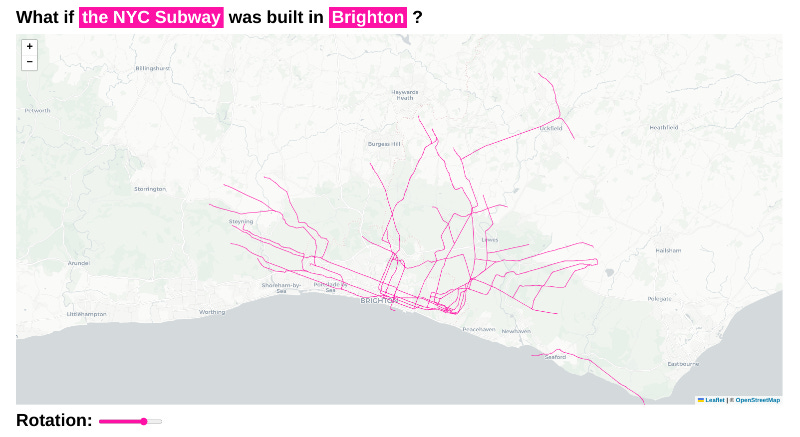

Maps of the week: geographically accurate versions of the wrong metro networks

Some years ago, in the early days of the late, lamented CityMetric, I went through a phase of putting bits of maps on other maps. I’d drop Manhattan Island onto the British capital, or drag it out into the Thames estuary; superimpose the official boundaries of Paris on to London; and so on. This did have a purpose, of sorts – to compare scales, or show how the official population stats of the two cities weren’t actually comparable; Paris proper is more like zones one and two. But the main reason I did it was because I wanted to and I’d somehow found myself a job in which I could and call it work. Golden years.

One which frankly didn’t come off was an attempt to show how far the Paris Metro would spread in my own city. I was trying to highlight the difference in the station density of the two cities’ transport networks – partly to make a point about how the two worked, partly because I’m the kind of freak who got his kicks from imagining what London would be like with a lot more stations. But I lacked the technical skills to do it, and the resulting map was so unreadable that whoever is keeping an eye on CityMetric – it’s CityMonitor these days – has amended the article and made the map tiny to spare my blushes.

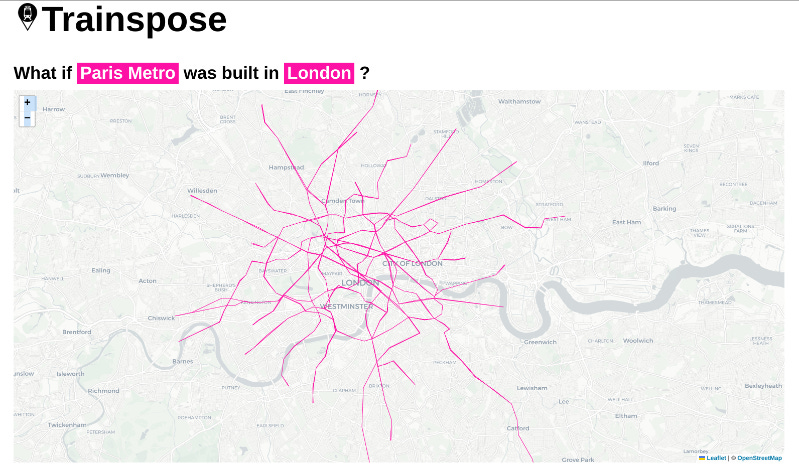

With today’s technology, though, I can do it in seconds, thanks to a delightful site called Trainspose. Look:

With the heart of Paris, Ile de la Cite, dropped onto London’s official centre at Charing Cross, you can immediately see that the vast majority of the network barely extends beyond zone 1. And it’s far neater than my effort.

In fact, the site allows you to drop any network on any city at any angle. By reangling it a bit to send the rather more ambitious line 14 to Bath instead of Orly Airport, you can see the Metro network is actually a pretty good size for Bristol:

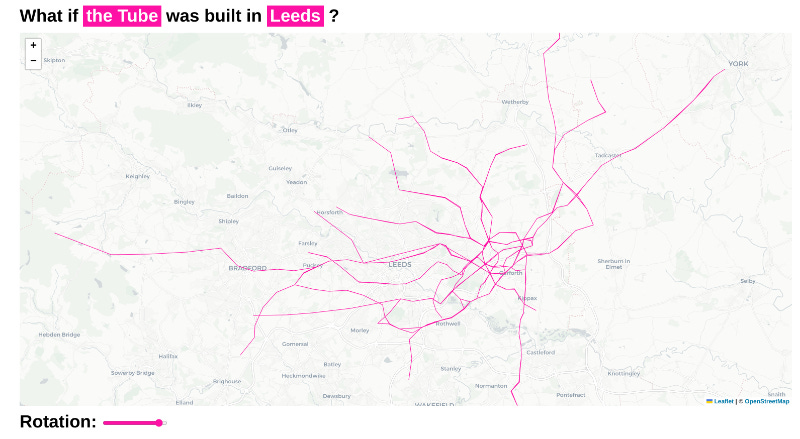

Leeds is rightly angry about its lack of a metro network, so why not give it a tube?

Hours of fun for all the family!

You can play with the map yourself here.

All images courtesy of Trainspose.

f you enjoyed this, and would like to get a weekly newsletter full of such goodies, but can’t currently afford a subscription, then hit reply and ask nicely and I’ll give you a comp. If you can afford it, though, and want more of it, then:

An aside but does anyone of roughly my age remember quite how incredible Microsoft Encarta felt when it first came along?