As the World Falls Down

This week: well, the western alliance had a good run. Also: some Great Fires; and British incomes in one chart.

For a few months short of a century before the First World War, Europe had known peace. This is an over-simplification: there had been war in Crimea; Prussia had fought three, in its attempts to unify Germany.1 The idea of a century of peace also ignores the extensive atrocities Europeans were committing a very long way from Europe, the US Civil War, and China’s Taiping Rebellion which, despite its rather unprepossessing name, likely killed more people than the actual First World War.

Most of those things, though, were a long way from London. In 1914, if you were young and British and weren’t involved in the administration of the empire, then it wasn’t just you that had only ever known peace. It was likely all your parents had known, and your grandparents, and probably their parents, too. There is a reason we remember the First World War as a disaster that came from a clear blue sky, and forget the reality of the political tension and grey, humid summer that actually preceded it.

I’ve made this point before I know, though I didn’t realise until just now that I made it as recently as four weeks ago. But I keep thinking about it, because it isn’t getting less relevant. The last eight decades were not, for everybody, peaceful; more than half of them were overshadowed by the threat of complete and utter annihilation. But while there were looming worries and distant conflicts and terrorism and so on, it was nonetheless the case that, if you lived in western Europe, the reality of war was unlikely to be a big feature of your life. This is, historically, unusual. And it was true – though we often bridled against it – because the world’s biggest superpower was committed to defending us.

Well. It was nice while it lasted.

There are two other unnerving things about the speech that JD Vance gave in Munich this week. (Nothing good in international relations ever seems to happen in Munich, does it?) One is that it is abundantly clear that the administration sees the world not in terms of geopolitical interests, but of ideological alignment.2 The US is now pro-Russia, because it is governed from the authoritarian, nationalist right; it is anti-European because, for the most part, Europe currently isn’t. The idea of an international nationalist movement always seemed absurd and paradoxical to me, but nonetheless the US government clearly no longer believes liberal values are worth holding, let alone fighting to defend. Very well.

The other is, of course, Ukraine – not just the fate of the country itself, but what it represents. Once upon a time, carving up weak states at conferences to which their governments were not invited was the sort of thing great powers did rather a lot: it happened to Poland in the 1790s, to the entire continent of Africa in the 1880s, to Poland again in 1939.

Since 1945, though, it’s been generally assumed that this is Not Done. There’s no shortage of examples of big powers pushing little ones around, if not deposing their governments altogether, but there has been at least a polite fiction that national sovereignty matters; that international relations is about legality, as well as power.

The US-Russia Summit in Saudi Arabia – that choice of venue, too, feels a bad sign – may not end the war against Ukraine’s will, because it’s Ukrainians who are doing the actual fighting. Nonetheless, the return of the assumption that big powers can simply carve bits off smaller ones is a deeply unsettling development. It’s another way we may come to see the “post-war era” as a golden period which has now reached its end.

Some cheerier content follows. If you’re interested in defence policy, international relations and so on, though, it’s worth checking out the newly arrived newsletter from my friend Luke McGee, late of CNN. Here’s his latest bit, about how just throwing money at European defence without thinking of what to spend it on might be a bad idea.

Some book news! (Not my own)

A year or two back, a historian who’d been a long-time Twitter mutual reached out for advice about an idea for a book she wanted to write about the legacy of the Roman Empire. This was in the summer of 2023, when I was at my post-bereavement lowest, which leads me to suspect the point was never really the advice, but the reaching out. That was the sort of thing that was happening a lot around then, and I appreciated it a great deal.

Anyway, we kept talking, about Rome and Andor and all sorts of other things, and she was kind enough to read a draft of 47 Borders for me in search of howlers, and unsurprisingly a publisher snapped up her book proposal, and last year by a pool in Lisbon I read a draft. And approximately once a week since, I have bothered her to ask if I’m allowed to talk about it on this newsletter yet, because it’s great, and because a sizable proportion of you people will love it.

Last week, Aurum Press finally announced that Rhiannon Garth Jones’ All Roads Lead to Rome: Why we think about the Roman Empire daily will be published on 22 May.

And you should absolutely pre-order it, right this very second.

The Great Fire Of-

The Great Fire of Rome (18 July 64CE)

Probably the origin of the idea of a “great fire” (incendium magnum). Started in the shops around the Circus Maximus, then, thanks to strong July winds, spread the whole length of that chariot stadium and well beyond. Destroyed 70% of the city, and killed hundreds. The Emperor Nero blamed Christians; everyone else blamed Nero. Actually probably an accident. Fires in Rome happened all the time: if you crammed over a million people into that small a space, it was inevitable that one would spread eventually.

After the fire, debris was used to fill in malarial marshes nearby, while Nero introduced new rules which increased the width of streets to make a recurrence less likely. He probably didn’t fiddle while Rome burned, however. Suetonius has him weeping and watching the city burn from atop the city walls; Dio Cassius has him dressed as a player of the cithara, a sort of lute. All this feels like the sort of post hoc briefing that a lot of emperors who were later assassinated, requiring post hoc justifications, got stiffed with.

Before you feel too warmly towards the guy, though, he also built himself a massive palace on the land the fire cleared, so.3

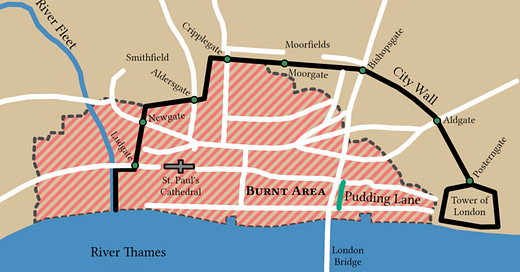

The Great Fire of London (2-6 September 1666)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.