Could Cornwall really become the fifth nation of the UK?

Or: what is a nation, anyway?

In 1956, Malta failed in its bid to become the fifth nation of the UK; in 2025, a new contender has emerged. There’s been a petition. There’s been a vote. There’s been a government response that can be translated as “Bugger off and stop being silly”, admittedly – but if history holds any lessons, it’s that nationalism can’t always be put back in the box, even when outsiders think it ridiculous.

So – could Cornwall really take its place in the brotherhood of nations? And what would it mean if it did?

The story so far

The petition appeared on the Parliament website two days after Christmas 2024. Try not to quake too much as you read its demands (or, come to that, its American spelling):

“We urge the UK Government to formally recognize Cornwall as a nation, granting it equal status to Wales and Scotland. This includes devolved powers, cultural preservation, and official recognition of Cornwall’s distinct heritage, language, and historic autonomy.

“Cornwall has a rich cultural and historical identity, distinct from the rest of England, with its own language, Kernewek, and heritage. Despite being part of the UK, Cornwall’s history as a Duchy reflects its unique status. We think granting Cornwall nation status would preserve its culture, promote self-governance, and could empower its people to address local issues.”

People post a lot of petitions to this website – a couple of dozen more appeared just in the two days before I wrote this, covering everything from mayoral term limits to pensions for Gurkhas to making tattoo artistry a licensed profession. Very few of them get news coverage or even, frankly, noticed.

The reason this one is at least slightly different is that the council got behind it. In late July, Councilor Dick Cole – leader of Mebyon Kernow, the peninsula’s answer to Plaid Cymru or the SNP – put forward a motion demanding the British government recognise Cornwall as a nation. That passed by 53 to 22, with two abstentions and opposition overwhelmingly concentrated among Reform. “This is not a slogan or a branding exercise,” said the council’s leader, LibDem Leigh Frost. “It is a statement of fact and a declaration of intent.”1

I’m not sure how many people had signed the petition before this – I suspect, given it had been sitting there seven months already, it was the vote that lit the fire. But shortly afterwards, it had hit 12,000 signatures, and got write ups from the likes of the Times and BBC. In August, Frost released a video encouraging more people to sign. “This isn’t about independence, it never has been,” he says, while walking about for some reason. “This is about making sure decisions about Cornwall are made in Cornwall.”

Is it actually a nation, though?

Cornwall was one of the last counties to be incorporated into England, probably sometime in the 10th century. (It’s a bit hazy.) As with other rugged and far-flung regions like Cumbria and Wales, it retained much of its previous Romano-British identity, speaking a local variant of the Brittonic language (Cornish, or Kernewek), long after the lowland part of the island had switched to English. It all fits neatly into our traditional but quite possibly misleading national story, of the original inhabitants of the island being driven to its rockier fringes by the Anglo-Saxon invaders.

There are two main planks to the argument that Cornwall had a different relationship to England and Englishness than, say, Lancashire. One is that it had its own parliament, the Stannary Parliament, right up until 1753. How big a deal this is depends on who you ask and which side they’re on: some point out it merely oversaw the tin trade, making it sound like more of a guild than a representative body; others, that the industry was so powerful locally that the Stannators (great word) could effectively pass legislation governing everyone in Cornwall. Could go either way.

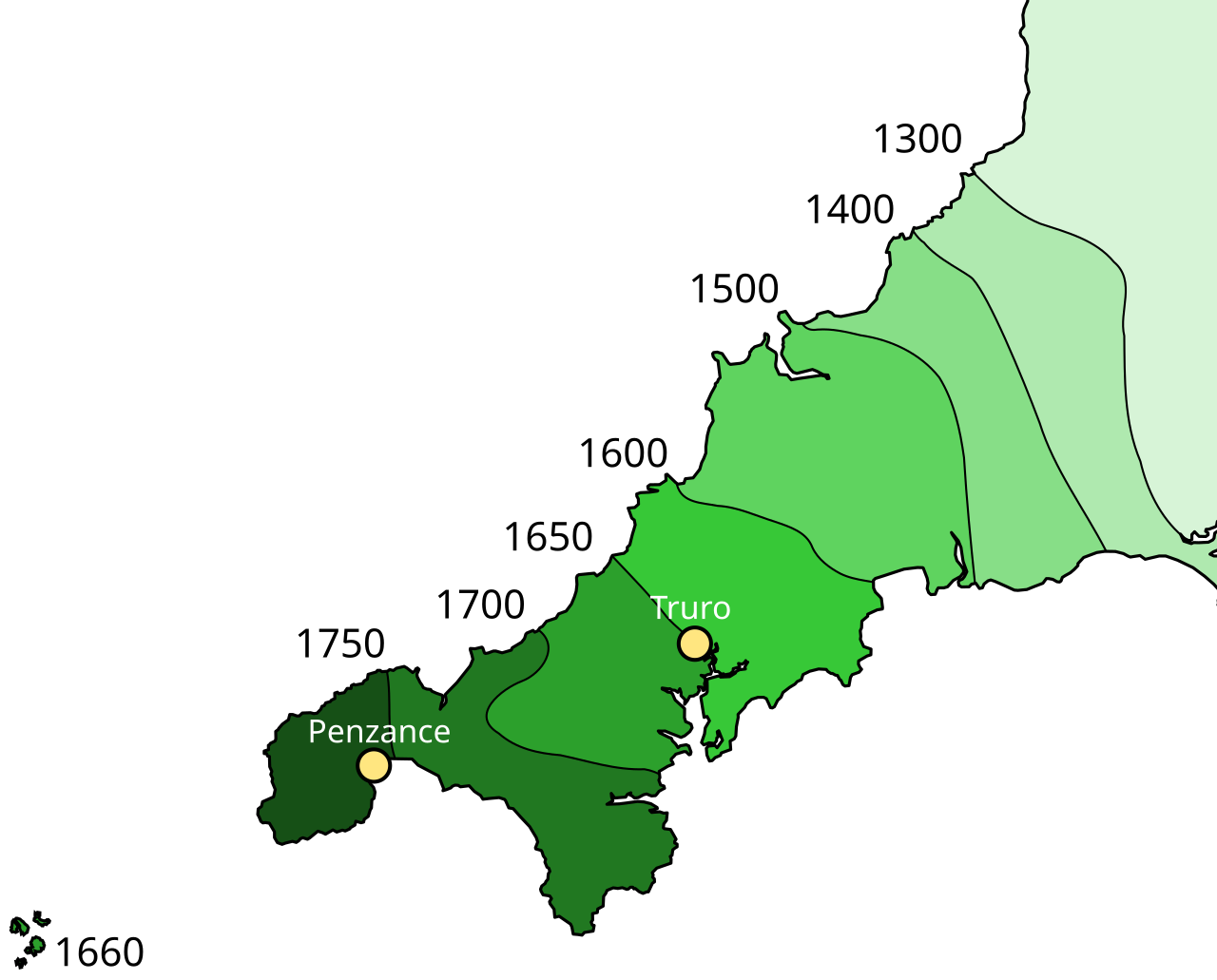

The other is the persistence of Cornish which, like its close relative across the sea in Wales, outlived the Middle Ages. Gradually, though, English encroached further and further west. Here’s a suspiciously neat map:

There were a lot of vaguely nation-shaped identities about the place prior to 1750 which we probably wouldn’t recognise as nations now (when did you last hear someone describe themselves as a Burgundian or a Prussian?), not to mention plenty we do recognise that didn’t exist then. And it is an unfortunate but inescapable fact that Cornish stopped being a living language at least 134 years ago and quite possibly considerably longer than that. Cornish didn’t decline or go into hiding; it died, and may have done so even before codifying national identities, or sometimes inventing them wholesale, became all the rage. Bummer.

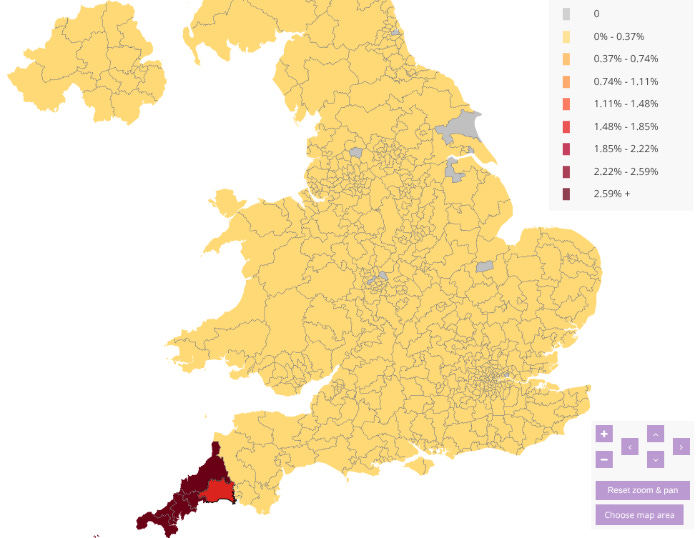

But while a language certainly helps create or maintain a nationality, it’s not actually the same thing: more important, surely, is how people feel today. There, the news is mixed. Following a push from the council, the proportion of people in Cornwall who claim Cornish as a national identity is on the rise, from 10.9% in 2011 to 15% in 2021. That’s a big jump! It’s still not many.

So, at risk of getting murdered by the Cornish National Liberation Army – a real thing, which at one time had as many as 30 members – I’m going to suggest the claim that Cornwall is the same as Scotland or Wales is pushing it. It might, indeed, be considered a little offensive to the Scottish or the Welsh. The formulation a lot of commentary seems to have settled on is “the Duchy”. This is accurate – Cornwall was one – but it also carries a meaning we don’t quite have a concept for any more, that of a region clearly attached to a bigger power but at least slightly independent of it. Normandy and Brittany were duchies; so were Schleswig and Holstein and Bavaria. That does feel like the right term for Cornwall and its relationship to England.2

The only slight problem here of course is that we are a couple of centuries into a world dominated by sovereign nation states, and nobody gives a hoot what a duchy is any more.

What is this really about?

On 15 September, the British government – which clearly fears the Cornish uprising and/or hates democracy – closed the petition. By then, the number of signatories stood at 24,011: an impressive doubling since the end of July. But it was still not, to be clear, that many – over half a million people live in Cornwall, a figure the most popular petitions on the site smash through. So, perhaps unsurprisingly, the government laughed it off. Here’s its official response, edited for length and not dying of boredom:

Government policy is to grant greater powers and ensure preservation of local culture, heritage and language through empowered Mayors of Strategic Authorities.

(...)

Cornwall’s National Minority Status does not prevent it from partnering with neighbouring authorities and Government would ensure that this status would be preserved in any future devolution arrangement. The Government does not plan to change Cornwall’s constitutional status otherwise.

So, is that the end of that? I suspect it isn’t. Because largely unnoticed in distant London – or, come to that, distant everywhere else – the campaign to rethink Cornwall’s constitutional status has actually been rumbling for quite a while.

A MORI poll, commissioned by the council, found 55% support for a fully devolved Cornish Assembly all the way back in 2003. (The following year, the Blair government’s plans for a North East regional assembly were rejected at a referendum, and that was the end of that.) In 2015, the county became the first non metro area to receive a devolution deal, enabling it to create its own transport body, “Transport for Cornwall” (Karyans rag Kernow), and then to keep all the business rates paid on its patch. (How generous the Whitehall machine can be!) All this fits with the whole Duchy thing: Cornwall is attached to England, but gets certain special powers.

Further devolution was agreed in principle in 2022, but hit a couple of snags. Firstly, the line from the last government was, basically, no mayor, no devolution, and Cornwall didn’t want a mayor. (It still doesn’t.) Then came the general election, which distracted everybody but didn’t unblock anything because the line from the current government is, basically, no mayor, no devolution, too. In 2024, the Institute of Cornish Studies at the University of (this is disappointing) Exeter published Devolution for Cornwall: One of Britain’s Oldest Nations, a paper making the case for the county’s unique identity, and signed by all six of its MPs, four Labour, two LibDem. It seems to have cut no ice.

Worst of all, from the perspective of the proud people of Cornwall, there’s been pressure to combine with either Plymouth (whose economic footprint extends west across the River Tamar) to form a “Plymwall” authority, or to just line up with Devon and form a South West one. This makes sense if you’re sat in Whitehall looking at spreadsheets: the direction of travel is towards larger councils, the economies of the two counties are pretty intertwined, geography of things like policing and the NHS already combine across the border… Why not stop messing about and bung them all in together?

Well, the reason why not is – nobody in Cornwall seems to want it. The county (duchy?) has a bunch of problems – poor infrastructure, distance from the centres of power, terrible poverty and a seasonal economy dependent on tourism – that Devon has either to a lesser degree or not at all. And Devon, unlike Cornwall, absolutely definitely is English. So all the county’s mayors, and every one of its MPs, have objected.

Reading between the lines of both Frost’s video message, and the government’s response, this seems to be what it’s really about. “You can’t just go shoving people into the same local government structures as those from an entirely different nation,” says the council leader. “Rational administration has nothing to do with nationhood,” replies the government, “so we can and we will.” To the politicians on the ground, a dividing line with Reform probably helps, too.

But let’s ignore the fact it clearly isn’t going to happen, and ask the question:

What would national recognition for Cornwall actually mean?

The answer is either pretty hazy, or pretty open, depending on how generous you want to be. We can probably assume some kind of devolved assembly, although how you’d make sure this wasn’t just a rebadged council is not entirely clear: that paper from the University of (it breaks my heart that it’s in Devon every time) Exeter suggests a Minister for Cornwall and a Cornwall Office.

Cllr Adam Paynter, Cornwall Council’s portfolio holder for Resources, whatever that is, has also said that the main benefit would be “to give Cornwall more control over its destiny and a distinct funding formula similar to Wales”. That implies the inclusion of the county/duchy/whatever in the Barnett Formula, through which the Treasury works out funding allocations for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Cornwall would be freed from the current system of council funding allocation, in which everything comes with strings attached, giving it both greater stability and greater control. All this could be used to safeguard the region’s language, heritage and so forth. Then again, it could be used to sort out the region’s infrastructure. The sky’s the limit.

Except it isn’t – because greater control does not automatically mean healthier finances. Done well, Cornwall levelling up from county to nation would give it powers to, say, tax the hell out of second homes and tourists, and invest in things benefiting residents. Done badly, it could reduce the tourism income the region relies on, while simultaneously making Westminster even less inclined to provide subsidies.

And if the government has set its face against it, it may be because such favours towards Cornwall surely risk escalation. There are other bits of England with some combination of strong regional identities and legitimate grievances against Westminster. Why should Cornwall get the powers to solve its problems while Yorkshire, say, does not?3 Why should a “nation” outrank somewhere with 10 times the people?

Come to that, if I were a Welsh nationalist – hailing from somewhere a mere five times the size, but which no one would doubt is a nation – I think I’d welcome Cornwall into the brotherhood of Celtic nations, then turn to the British government and demand more than they had because my country is proper. I’m a bit hazy on the details, but as I understand it there have been hints of this kind of dynamic in Spain: nations demanding extra powers; regions demanding parity; and round we go again.

So perhaps that’s why the British government isn’t keen.

Or perhaps this whole thing is silly

Or perhaps they just think this whole thing is silly. (I’m saying it twice, for emphasis.) I’ve been trying not to just say that but – well, maybe it is. There simply aren’t that many people in Cornwall – there are 15 times as many in London, and over half as many in my own, tiny borough alone. There’s a half remembered stand-up routine by Chris Addison in which he draws a distinction between a sensible separatist group like the SNP and the obviously absurd Cornish equivalent. He plays them with a squeaky high-pitched voice, and says they’ll have an economy based largely on fudge.

That’s why earlier I used the Cornish National Liberation Army – which has threatened English flags, English holiday homes, restaurants fronted by celebrity English chefs – as a punchline. Because the idea of a Cornish National Liberation Army feels inherently absurd.

Except – why should it be? Size isn’t everything. As that University of (one more time: awww) Exeter4 report notes, there are more people in Cornwall than in Iceland or Malta, and okay they’re islands, but nobody would question their nationhood. Cornwall is only a tad less populous than Europe’s newest country, Montenegro. There really is a Cornish language, and a Cornish flag. And even if there were not, if this is what the Cornish people wanted, then why should they not have it?

Maybe it wouldn’t be practical. But since when did nationalism worry about such things? Is there really any reason why Welsh nationalism should seem reasonable, but Cornish nationalism absurd?

One last observation, because I’ve gone on quite long enough. Earlier I noted that Cornwall, Wales, and Cumbria were all essentially the same people, the Romano-British, conquered by what became the English. What I didn’t dwell on was how the three experiences differed. Cornwall and Cumbria were probably pulled into England in the 10th century, the latter so completely that it’s always a surprise to be reminded that the Hen Ogledd (old north) ever even spoke a variant of Welsh. Wales itself was dominated from the 13th century and, from the 16th, looked set to be incorporated entirely – but in the end, it wasn’t.

Anyone who’s thought about the history of these islands will be very aware of the oppression of Wales, and at least a bit aware of Cornwall. Cumbria, though, was colonised by England so completely that we now forget it was ever otherwise.

The ultimate victory of imperialism comes when everyone forgets a province was ever conquered at all.

I’m a quarter Cumbrian, you know. Might campaign for that one myself.

If you enjoyed that and would like to read more things by me but can’t afford a subscription, just hit reply and ask: I will say yes, no questions asked. If you can afford one, though, you know the drill:

Go on, I’m trying to finish a book, I could do with all the good news I can get.

Reform are the largest bloc on the council but didn’t win a majority: it’s currently a LibDem/independent coalition.

Also, dukes outrank counts, so it implies being better than a county, so there.

Yorkshire was independent, of course, in its 9th-10th century phase as Viking-occupied Northumbria, sometimes known as Jorvik.

My co-conspirator and native Cornishman Tom Phillips would like you to know tht the University of Exeter has a campus in Penryn, and that is where the Institute of Cornish Studies is based. So there.