Gladstone, Homer and the “wine dark sea”: some notes on the history of colour

Or: when was an orange not coloured orange?

In 1858, William Ewart Gladstone – a former chancellor and future prime minister who was also, when not taking a slightly creepy interest in the moral salvation of prostitutes, a classicist – noticed something odd about the work of Homer: the world he depicts does not contain the colour blue. The only time the Greek word for the colour, “kyanós”, is used in either the Iliad or the Odyssey it refers to the eyebrows of Zeus: assuming the king of the gods was not some sort of Sonic the Hedgehog figure, that suggests the word then meant, simply, dark. The sky, in Homer’s telling, is instead like bronze.

That’s not the only weird thing about the colour scheme used by the poet. He used the same word, “chloros” – green – for honey, faces and wood. Most famously of all, he describes the sea as “oînops póntos”: literally, “wine-faced”, but translated most frequently as “wine-dark”. Oxen, too, were wine-dark. Oxen, sea, and wine do not, to our less mythic modern eyes, have much in the way of resemblance.

By far the most common colour terms in Homer, indeed, were “black” and “white”: not so much colours as the absence of them. Gladstone concluded from all this that the most ancient of Greeks didn’t see a world of colours, but one merely of light and dark. This has often been glossed as “Gladstone thought the Greeks were all colourblind” and sneered at accordingly, which unlike the sneering about the prostitutes thing is terribly unfair, because he didn’t really think that at all. Actually, something else seems to have been going on. The problem was linguistic: Homer’s work was written in the 8th century BCE, several centuries before the heyday of classical Athens. The Greeks of that era quite literally hadn’t found the words.

The human eye can see the difference between a near infinite number of different shades. They can be different “hues” (the technical term that means, basically, the colour bit of colour). But they can also have different saturation (are they vibrant or pale?) or luminosity (bright or dark?) levels, too, which is why attempts to define or represent the full range of colours resort to three-dimensional models. On top of that there are other, “dynamic” factors: whether they are glossy, or metallic, or iridescent (do they change with the viewing angle)? Are they opaque or translucent? We can’t possibly hope to name all of these shades in universally comprehensible ways, as valiantly as paint and crayon companies have been trying.

So, languages generally don’t. Instead, they rely on a relatively small number of basic colour terms: black, white, blue, yellow, red. A good test to check whether a colour is one of these elemental building blocks or not is to try to describe it in terms of other colours. Blue-green sounds meaningful; red-yellow does not. That suggests orange is universal enough to have ascended to the level of “basic colour term”, turquoise, so far, has not.

English has 11 of these terms (to complete the set: purple, brown, grey, pink), but some languages have more: Russians speakers, for example, make a distinction between “sinii” and “goluboi”, a dark and a light shade of what we would call blue, and will treat them as different colours in the same way we do red and pink.

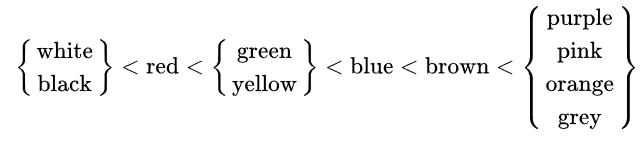

What does this have to do with Homer? In 1969, anthropologist Brent Berlin and linguist Paul Kay surveyed the history of 20 languages from around the world for their study Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution. What they found is that languages all seem to develop their basic colour terms in pretty much the same order. In stage one, they develop words for dark and light – essentially, much more broadly applicable versions of black and white. Red comes next, possibly because it’s the colour of blood, and one of the easiest dyes to make; then green, then yellow, or possibly yellow, then green; and so on. Here’s a diagram of the full pattern:

Suddenly, the oddity that Gladstone found in Homer doesn’t seem that odd any more: the Greek language at the time the poems were written was still somewhere on the left of the diagram, with words for black and white, red and a pale yellow-ish green, but had not yet come up with the other colours. The seas and oxen were wine-dark because there were not yet words for blue or brown: they were merely dark. (We call red wine red, but it’s much, much darker than, say, the red of a ladybird: perhaps the Greeks saw the darkness before the redness.)

How do we name colours? Broadly, their names can be split into two groups: abstract ones (words like “red” which refer only to themselves), and descriptive ones (which refer to other things you might actually encounter out there in the world). The obvious descriptive one is orange, which seems to have referred to the fruit before it referred to a colour1 – that suggests people adopted the name of the fruit to refer to that of its colour, in the same way we’ve done more recently with, say, lemon.

Oddly, though, it’s not the only example. Pink came from a flower (dianthus; carnations); purple referred to a dye, which took its name from a sea snail from which it had been derived. (Bad luck for the sea snail.) These are clearly not descriptive names now. But when they stopped being so is surprisingly hard to pin down.

I’ve found colours fascinating, ever since the first computer paint programme I had access to, some time in the late 1980s (I never managed to draw a thing, but I had a lot of fun mixing colours), so this is almost certainly a topic I’ll return to. But if you’d like to read more on all this, and why wouldn’t you, Alex Bellos’ 2010 review of Guy Deutscher’s book Through the Language Glass: How Words Colour Your World is a good place to start. I haven’t read the book yet, but you know what? I might.

Newsflash: Henry and I have returned home at last

The electricity required to run fans and thus keep my ridiculous dog cool in a heatwave isn’t cheap, of course, so here comes the sales pitch.

The article above is an extract from the archive of the Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything, a weekly newsletter which goes out every Wednesday at 4pm. This week’s edition concerned the most incredible graphic in Tory party history; some notes on education secretaries past; and a fantasy rail map of London. It was good. You’d have liked it.

So why not bite the bullet and become a paying subscriber? Every Wednesday afternoon, you’ll get a bit on politics, some diverting links, an article on something from history/geography/language/whatever I’ve been obsessing about this week, and the map of the week. You’ll also get a warm glow of satisfaction that you’re helping me to write fun and interesting things, not nasty corporate ones. And all for just £4 a month or £40£28 a year! God I’m basically robbing myself here aren’t I.

Talking of which: I’m aware we’re all broke right now. If you can’t currently justify paying for some nerd’s substack (unemployed, underemployed, impoverished student, and so forth), just hit reply and ask nicely and I’ll give you a complimentary subscription, no questions asked. I am literally giving it away.

Alternatively, why not pre-order my new book, out next April? Go on, the more this thing sells, the more free newsletters I can dole out.

Anyway, if anyone needs me I’ll be next to a fan.

It can also, of course, refer to a place, as in “William of”; confusingly, the principality in question is not in the Netherlands, but in southern France.