For the last few months, in an attempt to cover US politics without just staring, gibbering, at the polls, I’ve been writing potted bios of some of the less remembered presidents. I think, if I’m entirely honest with you, I’ve been trying to remind myself that, even if Donald Trump wins, there will come a point it not longer seems to matter. This too shall pass.

These columns have mostly been behind the paywall - but as the big day is finally approaching I figured I’d release the first two to free subscribers as a sort of omnibus. The others will follow at some point, just so long as any of us can still bear to think about the United States.

These originally went to paying subscribers on 11 September and 18 September. If you enjoy my unique approach of “covering the news by writing instead about the 19th century,” then why not join them?

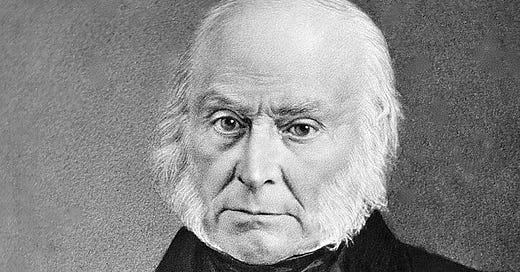

Half-Forgotten US President of the Week: John Quincy Adams

Lived: 1767-1848

6th President: 1825-1829

John Quincy Adams is the earliest president commonly referred to using his middle name. This is not unusual – JFK, LBJ and so on – but in this particular case it’s more like George W. Bush: the reason you need the “Quincy” is specifically to distinguish the guy from John Adams, who had also been president and who, by a staggering coincidence, was John Quincy Adams’ dad. Between the moment the American Revolution threw off the shackles of hereditary monarchy, and the one when dynastic politics reached the White House, there passed just 48 years. Great work.1 The “Quincy”, incidentally, was to honour the notorious JQA’s maternal great-grandfather Colonel John Quincy, who died two days after his birth.

Adams Jr was a high flyer even before his dad was president: after Harvard, he was appointed ambassador to the Netherlands by George Washington at the age of just 26, and was later sent to Prussia and Russia, too. After stints as state senator for, then US senator from, Massachusetts, President James Monroe appointed him as his secretary of state. In that role, he agreed with Spain the terms by which Florida would become part of US; negotiated with Britain to jointly occupy Oregon Country (today’s Pacific Northwest and British Columbia); and was the first to formulate the novel and then mildly optimistic idea that any interference by European powers anywhere in the Americans was a hostile act against the United States. (Sure, why not.) He’d probably be a bit annoyed to learn that, by the time this policy became believable, everyone would call it the “Monroe Doctrine”, after his boss.

John Quincy Adams’ arrival as president in the election of 1824 – hey, it’s the 200th anniversary! I hadn’t even noticed – wasn’t noteworthy just for its nepo baby overtones. He was also the first president elected without winning the popular vote, like George W. Bush in 2000 or Donald Trump in 2016. Unlike those guys, though, Adams didn’t win the electoral college vote, either.

At the time, you see, the US only really had one political party, which seems a bit mad: the result was that four different Democratic-Republican candidates contested the presidency that year. Because none of them came close to a majority in the electoral college, though, the decision went to the House of Representatives, where every state delegation got to cast a single vote. JQA won 13 of the 24 states, thanks in large part to a bargain with fourth-placed candidate Henry Clay, who’d helpfully dropped out, and who Adams promptly named as his secretary of state. All this smelled a bit – the new president had won just 33% of the vote, compared to over 40% for leading candidate, Andrew Jackson – and so his political enemies almost immediately began plotting their revenge against this “corrupt bargain”.

What did Adams do with the presidency once he’d won it? He began building roads and canals, to bind the huge new country together. He argued fervently for the creation of a national university and observatory, and the public financing of science and the arts. All this is the sort of programme I personally approve of, which is generally a bad sign for any politician, and true to form his critics called it unconstitutional and he got absolutely whopped in 1828. Andrew Jackson, again, won in a landslide (56% to 44%, 178 electoral college votes to 83) and promptly set about trying to do horrible things to the native Americans. JQA moped a bit, but was elected to the House of Representatives in 1830, and spent the last two decades of his life campaigning against the expansion of slavery. Fair play.

So: John Quincy Adams was probably alright, really. But he and John Adams were the only two of the first seven presidents not to serve a second term – both did try – and unlike his dad, the 6th president didn’t even get a prestige HBO series in his name. Bummer.

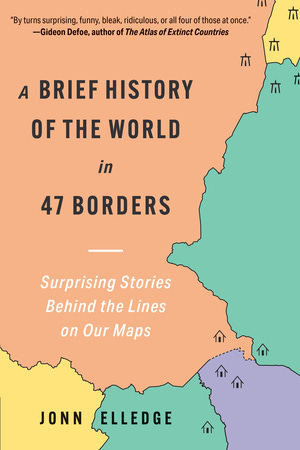

Half-Forgotten US President of the Week: John Tyler

Lived: 1790-1862

10th President: 1841-1845

“Aha!” you may be thinking. “I know that name! This one’s actually in that Simpsons song!”

And so he is. But that is not the most important thing about him! The most important things to know about John Tyler – or at least, the three things I know of him straight off the bat and thus assume are most important – are these:

He became president by mistake;

He still (I know this sounds mad, but it’s true) has a living grandchild;

There's a song about him that's an absolutely terrible earworm.

Tyler was not quite the first president to be born after the Declaration of Independence – that was his predecessor but one, Martin Van Buren – but he was pretty close. Born in 1790, he grew up in a prominent slaveholding family – great start – the son of John Tyler Sr, a planter, lawyer and college roommate of Thomas Jefferson who later served as governor of Virginia.2 (Amazing how much you can cram in when other people are doing all the hard work on your farm, whether they want to do that or not.)

John Tyler Jr was a chip off the old block, and followed a very similar path, training as a lawyer before embarking on a political career (House of Representatives, governor’s mansion, Senate), pausing only briefly to fight the War of 1812 against the British along the way. He could do all these things because he kept a bunch of human beings, some of whom he’d literally inherited from his father, as property, and made them do all the actual farming. God, the past is horrible.

All this gave Tyler a lot of street-cred as a fervent supporter of “states’ rights”, a phrase which was not entirely, just mostly, a euphemism for the right of wealthy southern landowners to keep slaves. Somebody who lacked that street cred was the Ohio-born William Henry Harrison: he was the hero of the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe on the Indiana Frontier, so he had the “beating the crap out of the Indians” vote locked up; the “keeping other human beings as chattel” one, though, not so much.

So when Harrison ran for president in 1840, he nominated Tyler as Vice President, to shore up his votes in the south; then beat the incumbent, the aforementioned Martin Van Buren, to become the first president from the hilariously short-lived Whig party. I’m not saying the catchy campaign song “Tippecanoe & Tyler Too” was the reason for that; but I am saying that it’s the only political campaign song from the 1840s I can actually sing.

Alas for William Henry Harrison – you probably know this bit – he failed to wear a coat to his inauguration ceremony on a cold, wet day, delivered the longest inaugural address in US history (two bleedin’ hours!), caught a chill and promptly died. He’d been in office just a month.3

What was meant to happen next was not exactly clear. The constitution said that, should the president be unavailable (resignation, death and so forth), his powers “shall devolve on the Vice President”. Many contemporaries argued that this meant he acted as a sort of supply president, not that he actually got the job. Tyler, though, had no such doubts, immediately arranged to take the oath of office and started generally presidenting.

This rather annoyed his Whig colleagues. Firstly, the perennial presidential candidate Henry Clay – last seen on these pages doing a deal with John Quincy Adams to become secretary of state – had rather hoped to get another go, and didn’t want Tyler in his way. Secondly, Tyler was rather out of step with his party, which was becoming increasingly northern, urban, and bourgeois in tone, rather like Harrison had been. The new president quickly acquired an irritating habit of vetoing any bit of legislation he thought breached states’ rights.

The result was a political crisis so hilarious it really deserves to be better known. The Whigs threw him, a sitting president, out of their party. His entire cabinet except one, Secretary of State Daniel Webster, resigned. For the first time, Congress overturned a presidential veto. Most delightfully of all, everyone started calling Tyler “his accidency”.

Not for the last time, a president dealt with being on the ropes at home by throwing himself into foreign policy, concluding treaties with Britain and China. He also pushed hard for the annexation of Texas – which had, as readers of my book will recall, been Mexican territory – thus setting the stage for the US to go to war with a) Mexico and b) itself. It wasn’t a great presidency.

Although Tyler was implicated in his country’s long slide towards civil war, he did at least attempt to prevent it too, joining the last ditch peace conference held in February 1861. When that failed, he committed to confederacy and would have represented Virginia in its Congress, had he not died first. The only positive legacy is that campaign song. It really is a banger:

The 2004 cover version by They Might Be Giants.

Oh, the grandchild! In 1844, following the death of first wife, Tyler secretly married a woman 30 years his junior, the 24 year old Julia Gardiner. They had seven children, one of whom, Lyon Gardiner Tyler, would follow in his dad’s footsteps by marrying a second wife, Sue Ruffin, nearly 35 years his junior. One of their sons, Lyon Gardiner Tyler Jr, survived until 2020, when he died aged 95. Another, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, born in 1928, was reported to be still going as recently as January. So yes, it is entirely possible to be alive in the 21st century, and have a grandfather born in the 18th. Cool.

If you want to read more stuff like this/support the kind of nerd who writes it, then as ever paying subscribers get more things, much earlier!

If you can’t afford to pay then just hit reply and you can have a freebie (really, it’s not a trick; if you already did this and I didn’t reply it’s because I missed the email, just kick me again). But if you can, here’s a convenient button to help with that:

Hell, do it before election day, and I’ll even give you a discount:

And if you enjoyed all that, you might also enjoy my book which also, as it happens, makes a brilliant Christmas present:

Also now available in North America!

Two other presidents descended from other presidents would follow: neither of them, oddly, is Franklin D. Roosevelt, who’s not especially closely related to Theodore (5th cousins: a shared great-great-great-great-grandparent). The actual presidential nepo babies are the aforementioned George W. Bush, and Benjamin Harrison, who we may get to later.

He was also commonly referred to, for reasons I’m going to let you take an educated guess at, as “Judge Tyler”.

Another theory, which I first learned of from the Washington Post’s quite brilliant Presidential podcast from 2016, is that there was an unhealthily close relationship between the local sewage system and the White House water supply. Over the next few years there were a lot of untimely deaths in and around the White House. More here.