Hate To Say I Told You So

How our hunger for social media clout has sent tribalism soaring. Also this week: a forgotten British filmmaker; and the story of an even older historic border, sort of.

“What fools we were to give Donald Trump the benefit of the doubt,” began the headline of Andrew Neil’s Mail column last weekend. “He’s an unprincipled, narcissistic charlatan who doesn’t give a damn about democracy.”

That is, it must be said, an interesting use of the word “we”, but it might, to be fair, encompass the sort of people who write for and read the Daily Mail, so on this occasion I’ll allow it. Neil’s column, the headline of which has since been amended, goes on to argue that “the real Trump” has been clear since 6 January 2021, and “those of us who wished for better should have known better”. Perhaps, too, they should have resisted the impulse to write umpteen columns about how thrilling it would be to see him own the libs.

A few days ago, infuriated by the British government’s enthusiastic promise to cut disability benefits, I re-promoted the issue of this newsletter outlining my disillusionment under the headline, “But what’s it for?” Some will see a parallel between Neil’s open-mouthed horror at Trump’s turning out to be exactly who he’d told us he was, and my frustrated response to Starmer. Fair enough. While I was never particularly enthusiastic about the guy, and there remain plenty of sizable and important differences between the two men, when people say “I told you so” I wish I had a stronger response. That is one of the reasons I wrote that piece in the first place.

There is, though, another parallel between the two things, this time between where Neil finds himself and the people who’ve been yelling at me. Both, at some point, involved someone cheering when a self-evidently bad thing happened, for no other reasons than that other people they disliked were upset by it. I’m not entirely convinced this is a good thing.

Twitter poisoning – I am still determined to make fetch happen – is something that, once you’ve noticed it, you start to see everywhere. It was in the glee from much of the Labour right at the party’s ruinous 2019 election result. It’s in the way parts of the left persuaded themselves to back Brexit, or have now begun to argue that we don’t need to build houses, ostensibly because the people on the internet they find most annoying think the opposite. (It’s not in the smile on the face of a child, but I seem to have accidentally started writing in that tone so now feel an overwhelming need to ironically undercut myself.)

And it is definitely in many of the positions taken by the right of late. Consider the way the Republicans have somehow persuaded themselves they’re in favour of Russian expansionism now, a position that would have been baffling to either Ronald Reagan or Joe McCarthy. Much of that is the Donald Trump personality cult at work, too, but I don’t think we should underplay the role of “Democrats on the internet saying the opposite”. In the same way, the obvious answer to why parts of the British Conservative party keep aligning themselves with pro-Trump positions which we know almost none of their voters hold is because those they define as “the other side” are doing the opposite. In the age of the internet, party politics abhors consensus.

A tendency to draw our views not from independent thought but from those of our peers is quite normal. We all, to some extent, outsource our opinions to people that we trust: there are simply too many stories and too many policies for anyone to put in the hard yards to understand them all firsthand.

The online version is something more, though. It’s not simply in aligning with those on your side, but against those on some other, even at the expense of your own interests. It’s not the politics of what works, but of what gets retweets.

Witness the gleeful response to the crash currently cascading its way through much of the financial markets. I too have had the urge to snigger at Elon Musk’s diminishing portfolio, but even so it’s in none of our interests that Trump trashes the economy, because the discomfort he may suffer from a bad set of midterms is nothing to the pain the rest of us will feel, whether through collapsing investments or a shrinking job market. Being able to say “I told you so” is fun. Having a functional planet and being able to eat must surely count for more.

‘ark at Taylor Swift over here

Some dates for my global* book tour:

Thursday 3 April: Waterstones St Albans

Friday 4 April: Interintellect Salon

Thursday 10 April: Waterstones London Piccadilly (with Rob Hutton)

Sunday 13 April: Guildford Literary Festival

Monday 14 April: Waterstones Liverpool (with Neil Atkinson)

Tuesday 29 April: Waterstones York

Tuesday 6 May: Foyles London Charing Cross

Thursday 8 May: Stratford Literary Festival

Having been asked why I’m not going to, variously, the south coast, Scotland, Canada and Dubai, I should specify that I’m trying to say yes to everything I’m invited to. If you happen to be in possession of a book shop or literary festival, I’m a rampant self-publicist and love the sound of my own voice, so please do ask me.

“The greatest technician and the greatest poet of British cinema”

A few weeks ago while researching the history of the pedestrian crossing, as you do, I came across a delightful 1948 public information film meant to teach unwary pedestrians how to use one. It tells the story of “Mr A, a perfectly straightforward kind of person” who, the voiceover tells us, “reacts quite normally”: the mute, rubber-faced actor pulls a face to show his disgust at the idea of “dried egg for breakfast”; grins to suggest delight at it being pub opening time; looks truly horrified at the mention of his mother-in-law (it was 1948); and so on.

But Mr A has a problem: he struggles to cross the road without nearly getting mown down, in a surprisingly slapstick fashion. The voiceover suggests this might be a good moment to try the newly installed crossing point, marked by belisha beacons and two rows of studs. (The rather less missable zebra crossing would not be invented for another three years.) At first he dawdles, with predictable results; then at last learns to walk across at a normal speed. “It’s no good thinking you can have a sleep or eat your breakfast out there because you’ll soon find yourself in trouble,” says the voiceover accompanying a sequence that is so much more literal than you’re imagining it to be.

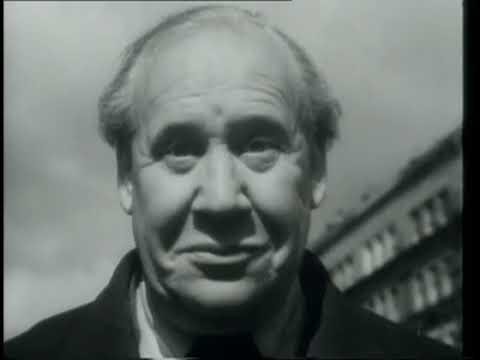

This oddly charming public information film was shown before cinema screenings1. Its goal was to teach people the purpose of the new crossings by showing someone dimmer than they are learning to use them. This, I learned from the replies when I posted the link to the video on BlueSky, was actually one of several dozen such films made by a little known but much feted writer/producer/director named Richard Massingham. You’d recognise his face. He’s the man who plays Mr A.

Born in Sleaford, Lincolnshire, in 1898, Massingham2 trained as a doctor, and rose to be senior medical officer at the London Fever Hospital. Alas he suffered from hypochondria – not a great choice of career, then, that – so over time his interest in filmmaking, initially a hobby, began to take over.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.