How AI ruined Quora

Fully automated luxury mansplaining.

This was sent to paying subscribers back in January.

I have, in my time, thrown a lot of questions at the internet. Why is there a Napoleon I and Napoleon III, but no Napoleon II.1 Why is Europe considered a continent when it is very clearly just a peninsula of Asia.2 Sometimes the answers to these questions end up in this newsletter as content; sometimes they end up coming out of my mouth in social situations, surprising and delighting my friends.

At some point – I’m not sure when – such questions led me to sign up to Quora, “a platform to ask questions and connect with people who contribute unique insights and quality answers”, which, annoyingly, you need to log into to read. I don’t remember what question led me there, let alone the quality of the answer, but I’m assuming – given both my interests, and the sort of thing it’s been spamming me with ever since – it was somewhere in the intersection of history, national identity and international relations. At any rate, for several years now, the site has been emailing me other examples of the sorts of questions the algorithm thinks I might be interested in. The fact it sends them to my backup email account, the one I use for group chats and other stuff I don’t want littering my main inbox, suggests that I saw this one coming.

For a long time, the sort of questions Quora would fire back at me, along with the first few words of the top ranked answer, made a pretty good fist of being Elledge-specific clickbait. “Why is England considered a country while the UK or Britain, which it is part of, is also a country?” “Why can’t we dig deeper than 12.2 km into the Earth?” “Did Henry VIII regret executing Thomas More?” And once upon a time, I’m told, the platform was actually rather good: a place filled with scientists and historians, where you might actually find an actual expert to answer your question.

In recent years, though, it’s gone noticeably downhill. The people most active on the platform today will show their bonafides not through their qualifications or professional status, but by listing the countries they’ve visited and the languages they speak. There’s something car-crash compelling about the tone of the site, too. In a manner familiar from food writers and also, I fear, this newsletter, answers to big questions will inevitably begin with half-remembered personal anecdotes, possibly dating back to the late 1970s. Quora taps into the urge many people feel, when exposed to an internet connection, to show off. It’s found a way to monetise mansplaining.

These days, it sometimes struggles to hit even those intellectual heights, and in recent months I’ve noticed the questions I’m emailed growing increasingly, mindbogglingly weird. “Why is King Charles not called ‘King Charles the Ninth’?” (Well, why would he be?) “Why is Paris not the capital of France?” (Did I miss a memo?) “Why do Brits call their currency ‘quid’? What’s wrong with calling it ‘pounds’ like everyone else does?” (Oooh, that was so close to being an excellent question.)

The site doesn’t make it easy to identify who is asking its questions – to find out, you have to go from the email, to the website, to the page for the specific question, to the button marked details, which is probably more clicking than I’m going to do for anything that isn’t a video of two mismatched animals who’ve somehow become best friends – and the internet is full of people demonstrating quite outstanding levels of stupidity so I never thought much of any of this.

Until, that is, I spotted an answer beginning with the phrase, “IDIOT QUORA PROMPT GENERATOR AGAIN!” Because it turns out, if you go to the bother of clicking from email, to website, to question, to details, a lot of these questions aren’t being asked by real people at all. They’re being asked by an AI.

Not all of them, to be clear: the ones apparently aimed at winding up specific groups (Americans, Europeans, and so on) are almost certainly being asked by other specific groups (Europeans, Americans, etc). But where the questions become almost gleefully absurd (”What are people wearing in heaven?”; “Which K-pop idol has a crush on you?”; “What can we say to our cats?”) they almost certainly didn’t come from a human being at all.

The reason this is happening, the tech writer Kate Bevan told me, when I called her to ask, essentially, WTF, is almost certainly because “artificial intelligence” is a deeply misleading name.

“The category error everyone makes,” she explained, “is to treat AI as a knowledge engine. It’s not: it’s spicy autocomplete.” AI based on machine learning such as the large language models (LLMs) that power Chat GPT, or the Quora Prompt Generator, are very good at pattern matching: predicting the next word in a sentence in a generally compelling manner. But, while that’s one aspect of intelligence, it’s far from the only one. This, Bevan says, is why AI is so bad at maths, or including the right number of fingers on pictures. “It doesn’t actually know anything. It’s just a copycat.”

So what the Quora Prompt Generator is doing is generating things that take the form of real questions, but have none of the actual content. “Why are there no colours in school books?” would be a good question, if there were not, but there are: the prompt generator just doesn’t know that, because it doesn’t know anything. In the same way, it doesn’t know that Donald Trump is clean shaven so asks “How long did it take for Trump to grow his hair and moustache?” It doesn’t know that restaurants, unlike bars, are allowed to serve children in most jurisdictions (“Are minors still getting served at restaurants?”) It doesn’t know that The Lord of the Rings is a work of fiction (“Does Cate Blanchett have any real life connection to Galadriel?”), that most common building materials are not electrified (“What happens if you step on concrete?”), that you can’t just stick a negative in a sentence and assume that you’ll get something meaningful (“How many Oscars has Tom Cruise not won?”). It doesn’t know anything.

The people who implemented the Quora Prompt Generator, however, do know something. They know that many people will still engage with even the stupider questions, because it provides an opportunity to show off to strangers on the internet. They know that most of them won’t click through, to check whether they’re actually talking to a real human being. And they know that all this will generate higher traffic and thus, it’s assumed, revenues. Some reports suggested that Quora is generating 40,000 questions a day using bots alone.

What they seem not to know, though, is that chasing engagement numbers at all costs, without stopping to think about whether those numbers are actually good, is the sort of thing that can kill a platform. I’m not going to name the website I’ve been involved in that abandoned its small but solid following in favour of chasing the same search traffic as every other media organisation, but suffice it to say I’ve not met anyone who actually reads it in years. So while I’ve no clue what Quora’s metrics look like, I’m cynical about whether this strategy is working for them. It looks, from the outside, like it’s turned a once useful website into a sea of meaninglessness: a machine for encouraging people to waste their time answering questions that nobody actually asked.

“One of the things everyone talks about with AI is the need to keep humans in the loop, to make sure the algorithms are as unbiased as possible,” says Bevan. “But you also need them to look at what’s coming out of them, and ask whether you want them to represent your organisation.” The current strategy, she adds, suggests no understanding of what Quora is or why people liked it in the first place: “It’s just to juice engagement. But the superficial engagement of having people going, Jesus, this is f-ing dreadful is not the same as posting a thoughtful question.

“If I were doing their strategy,” she adds, “I’d just say let people browse without logging in.” That would, at least, clear my inbox.

More terrible questions from the Quora Prompt Generator, should you want them, here.

Self-promotion corner

If you’d like to read stuff like this when I write it, rather than when I deign to release it from the paywall and often not even then, my rates are very reasonable. For just £4 a month, or £40£28 a year, you can get a weekly dose of politics, maps and nerdery like the above, plus some diverting links.

Alternatively, as ever, if you want to read the newsletter but for whatever reason can’t justify the money right now, just hit reply and ask. I always say yes. Really. And if you want to pay up to support my generous approach to these things, oh look here’s another button:

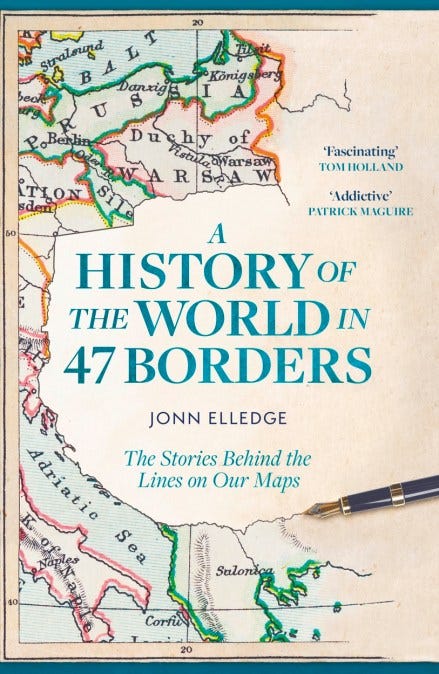

While we’re down here, surely you’ve bought your copy of my new book A History of the World in 47 Borders: The Stories Behind the Lines on Our Maps by now? Here's what Gideo Defoe said about it:

By turns surprising, funny, bleak, ridiculous, or all four of those at once, A History Of The World In 47 Borders unknots some of the weird historical and geographical tangles we've managed to get ourselves into. And it's timely too, if only because our preoccupation with drawing lines never seems to abate.

(Not only did he Gideon write the screenplay for The Pirates! In an Adventure with Scientists! which is brilliant, he also brought his excellent dog Noodle to my book launch, where he licked my nose. Big fan.)

There was! The great general and Emperor of the French abdicated in favour of his son, who rarely comes up in the history books because he never actually got to do any ruling and died at the court of his grandfather, Francis I of Austria, at the age of 21. His cousin, who later reinstated the French imperial throne, called himself Napoleon III out of respect.

Read my recently published book to find out why!