It’s Chrissssssssstmaaaaaaaas!

This yuletide: some notable Christmases, the true meaning of George Michael, and an attempt to map Santa’s journey.

No proper newsletter this week, because (I don’t know if you’ve noticed this, but) Wednesday is Christmas Day. I am thus enjoying a well-earned [please check – Jasper] break.

To tide you over, though, here’s some stuff I wrote around Christmases past. I’ll be back with new material in the new year.

Some notable Christmases

From last Christmas.

The first one. I’ve decided to do this chronologically, which was a stupid idea since it presents us with a problem at the very start. To whit: nobody knows when the first Christmas was. We have remarkably little clue when Jesus of Nazareth was born.

There was no year zero, of course: 1BC is followed by 1AD in the traditional Christian calendar, so logically it’d make sense for the messiah to be born on 25 December 1BC. This would be perfect, in fact: a Jewish boy’s bris is held on the 8th day of his life, so Jesus’ should have been on 1 January 1AD. A new age.

But there are very obvious reasons to think it unlikely the nativity took place in December at all: it’s a stupid time for the authorities to demand people move about for a census (although, to be fair, they probably didn’t do this at all); no one, in midwinter, is grazing their flocks by night; and so on. The decision to celebrate Christmas on 25 December seems to be a combination of piggybacking on other midwinter festivals such as Saturnalia, and the inevitable result of deciding that conception should take part at the spring equinox.

Then there’s the question of the year. The Gospels suggest that Jesus began his ministry in the 15th year of the reign of the Emperor Tiberius, when he was aged around 30: that suggests he began preaching in the late 20s AD, and was born several years earlier than 1BC. This fits nicely with the fact that Herod the Great, a figure mentioned explicitly in the Bible, died somewhere between 6BC and 4BC (the figure is, helpfully, debated).

Then again, we might be able to discount that, too: there’s no evidence he ever tried to commit the mass infanticide he’s accused of, and anyway regional kings were then in the habit of pretending they’d taken over earlier than they had for legitimacy reasons, making even the vague dates we have for his death suspect.

Anyway, the point is: we don’t know! Great start. Continuing with our theme:

c330? Maybe?1 St Nicholas, the possibly mythical bishop of Myra in what is now Turkey but what was then the Greek-speaking eastern Roman Empire, gives three girls some gold to use as dowries so they don’t have to get jobs as prostitutes. This, following some Dutch immigration to the United States and a fair bit of cleaning up, becomes a story about a nice old man who brings toys for children. Aww.

800. After rescuing a pope from some marauders, Charlemagne celebrates Christmas Day by being crowned emperor in Rome and pretending to be surprised about it. In doing so, he resurrects the western Roman Empire which had been dead for over three centuries, but puts so little effort into sorting out his own succession that his immediate descendants will spend much of the next century ripping it to shreds once again. (For more on this, buy my book!)

1066. In an absolutely shameless tribute act, William, Duke of Normandy, is crowned King of England on Christmas Day. Where once potential rulers pretended to be Roman, now they pretended to be Charlemagne.2

1610. Tinsel is invented in Nuremberg. So, now you know.

1640. The protestants who dominate Scotland’s parliament pass a law making celebrating Christmas illegal; England follows five years later. The ban is short-lived south of the border – once Charles II is restored to the throne in 1660 it’s party on, really – but Christmas remains verboten in Scotland rather longer, and does not officially become a public holiday until (this is mind blowing) 1958. This is why the Scots are so big on New Year.

1843. In October Charles Dickens, an established novelist panicking about the mismatch between the size of his family and that of his bank account, decides to cash in on the growing public interest in celebrating the Christmas season, and writes A Christmas Carol. In terms of both income and number of adaptations produced, the six weeks he spends on the book must have the highest return for any literary endeavour in the whole of human history.

The book does not include even a single Muppet.

1871. Boxing Day is established in England and Wales. The name dates from rather earlier, and seems to be related either to the money left in churches’ “Christmas boxes”, which was distributed among the poor on the day after Christmas, or to the tips and gifts (“boxes”) servants and other working-class people would spend the day demanding from those they’d served that year. But not for the first time in this story, no one seems quite sure.

1914. Some soldiers fighting World War One consider that maybe, instead of machine gunning each other, it would be more Christmassy to have a kick around instead. Shortly afterwards their senior officers make clear that, if they ever do it again, they’ll have them all shot, and that’s the end of that.

1946. The aforementioned It’s A Wonderful Life, the other canonical Christmas story, hits cinemas. I’ve always thought it made a good pairing with Carol: both involve supernatural figures investigating a broken, embittered man’s history, and showing him a world without him; both are about the importance of love and friendship, and how Christmas is the opposite of capitalism (when, let’s be honest, it is very much not). Really, I’m baffled people don’t bracket them together more often. Though not as baffled as I am by the fact that the film didn’t hit general release until January.

1973. In Britain, this was the year Slade’s Merry Xmas Everybody and Roy Wood & Wizzard’s Well I Wish It Could Be Christmas Every Day fought it out for Christmas number 1, thus establishing the idea of the Christmas chart battle. (Slade won, but I doubt Roy Wood has done badly out of it.)

I’ve often wondered why 1973 in particular was such a Christmassy year, which has given the festive season a certain glam rock vibe ever since. The answer, music writer and podcaster Andrew Hickey tells me, is that the previous year had seen the release of both John Lennon’s Happy Xmas (War is Over) and a reissue of Phil Spector’s 1963 Christmas album, thus establishing that the UK was ripe for a Christmas single.

All of which makes me wonder if I should have put 1972 as the notable Christmas? Oh well, I started as I meant to go on.

1984. Another chart battle: in this one, Band Aid kept Wham’s Last Christmas off the number one spot. George Michael, who sung on both records, donated all his royalties from the latter to Ethiopian famine relief anyway. God I love George Michael. Anyway: Wham finally hit number one shortly after Christmas in 2020.

Disappointingly, this was not, as I had confidently believed, also the year of The Snowman, which turns out to be from 1982. Never mind.

1989ish. Some time around then, I got a Scalextric. But, in a pleasing piece of thematic unity, I’m not sure exactly when.

This Christmas is probably not going to be as good as that one, if I’m honest.

Hey, talking of George Michael:

Some thoughts on the true meaning of Christmas

From 2022.

As the nights get darker, and the weather gets colder, and the festivities begin across the land, thoughts inevitably turn to a man whose life and death will always be associated with this time of year – a man whose purity of heart and good works alike contain, I think, the true spirit of the season.

George Michael was born Georgios Panayiotou in north London in 1963, the son of a Greek Cypriot restaurateur and his English dancer wife. He became obsessed with music after a bang on the head in the early 1970s, and in 1981, after a couple of false starts3, began his career when he formed a duo with his school friend Andrew Ridgeley. Over the next five years, Wham had a string of hits, in the UK and beyond, made the sort of money that most of us can only dream about, then decided to break up amicably and remain friends (another thing, I fear, of which many can only dream).

After that, Michael had a successful solo career, as well as occasionally replacing Freddie Mercury in Queen or dueting with Elton John. When he was arrested for cottaging in 1998 and forced to go public with his sexuality, he released Outside, a song about the joys of public indecency, alongside a video featuring examples thereof while Michael himself danced in a toilet dressed as a cop. In his latter years, his Twitter feed was a great source of indiscreet celebrity gossip, generally signed, “Lots of love, The Singing Greek xxx”.

And then, on Christmas Day 2016, he died. He was 53. That’s no age.

But the timing of his death is not the only reason we – or at least, I; I haven’t actually polled this – associate George Michael with Christmas. One is, of course, that you’re probably already sick of hearing Wham’s Last Christmas, for decades the UK’s highest selling single never to reach number one. (It lost the record when it finally did so last year, 37 years after its original release.) It failed to top the charts when first released back in 1984 because it was kept off the top spot by Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas?, which you’re also sick of hearing by now, and on which the duo also performed. Because their own song was in direct competition with the charity single, Michael and Ridgely agreed to donate the royalties from Last Christmas to Ethiopian famine relief, too.

This was, as it turned out, a quite astonishingly generous thing to do.

But it was also entirely in character. And that’s the other reason I associate George Michael with this time of year: because Christmas 2016 brought an absolute torrent of stories about quite how generous he was.

He donated his royalties from his 1991 duet with Elton John, Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me, to the Terrence Higgins Trust, which supports people living with HIV; those from 1996’s Jesus To A Child went to Childline. In 2006, he gave a free concert for nurses, to say thanks for the care the profession had given his mother during the last week of her life; more money still went to Macmillan Cancer Support.

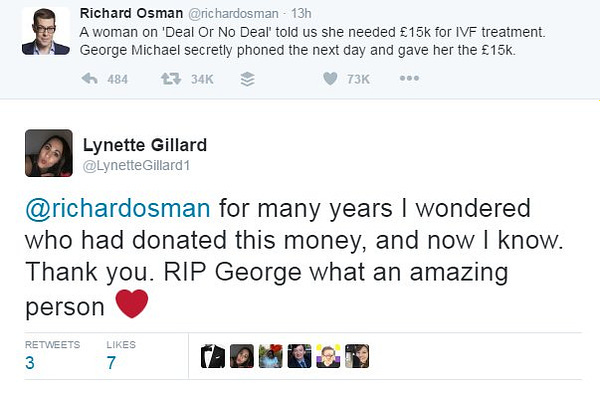

This is just scratching the surface. Every year Michael called Capital FM with a £100k donation to the Help A London Child campaign. He gave another £50k to send deprived kids to meet Santa in Lapland. The truly affecting stories, though, are the ones involving more personal forms of help. Working at a homeless shelter, and asking the team to keep it quiet. Phoning Deal or No Deal to give a contestant the money she’d failed to win to fund her IVF. Tipping a barmaid £5,000 to pay off her debts. This man was the ending of a Christmas movie made flesh.

Why are these stories so moving? Why, quite genuinely, do I read them again, to cheer myself up when feeling sad?

Many of us, I think, have been known to imagine how we’d act if we were rich. We think of the house we’d buy our parents, or the life changing help we’d offer friends. Perhaps we even imagine a more altruistic generosity, aimed at people we don’t know personally. What we’re telling ourselves when we do that is that we’d do things better than the people who are actually rich. Perhaps some of us would. But the evidence we have suggests many of us wouldn’t.4

George Michael actually did. He behaved as we like to imagine we would. The fact most of these stories did not come out in his lifetime is a reflection in part on the fact he genuinely wasn’t doing it to make himself look good: it’s just that he found himself in a position where he could help people, and so he did.

Forget Band Aid; forget Wham. That’s the real reason George Michael is the true meaning of Christmas.

Map of the week: Ho, ho, ho

Also from last Christmas.

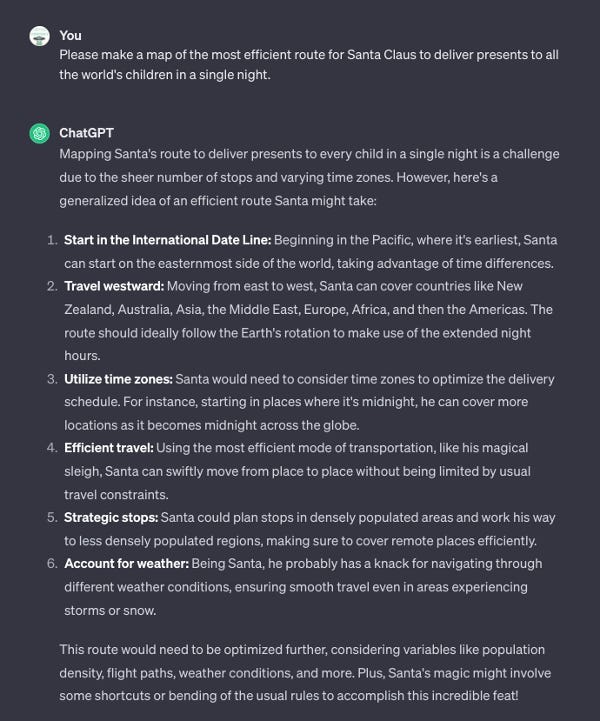

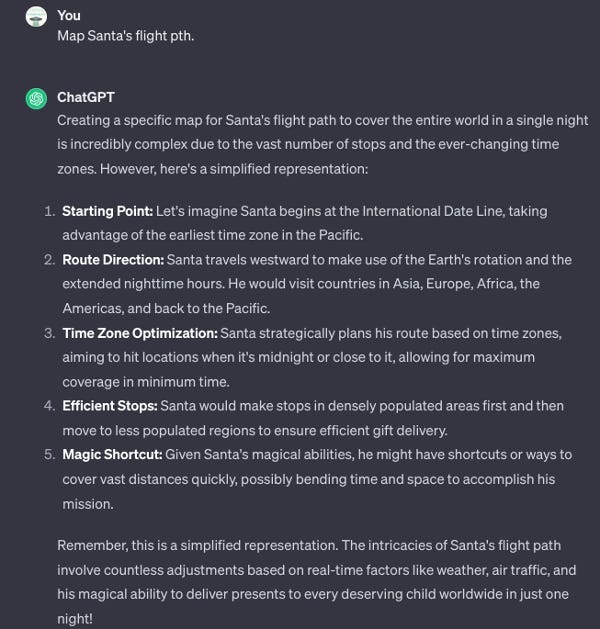

For this week’s map I wanted to do something special, I really did. Wouldn’t it be great, I thought, in what I imagined to be an incredibly clever brainwave, if I could do a map of the most efficient route Santa’s sleigh could take to deliver presents to all the world’s children in a single night? Okay, that was a bit beyond me technically; but isn’t that what AI is for? Have I finally found a real and valuable use for artificial intelligence?

So I asked ChatGPT. Here’s what happened:

This felt like a cop out, so I tried the more direct approach.

All of which leads me to suspect that a lot of other people have had this idea, and that the people behind the chatbot have told it not to waste its time. Oh well.

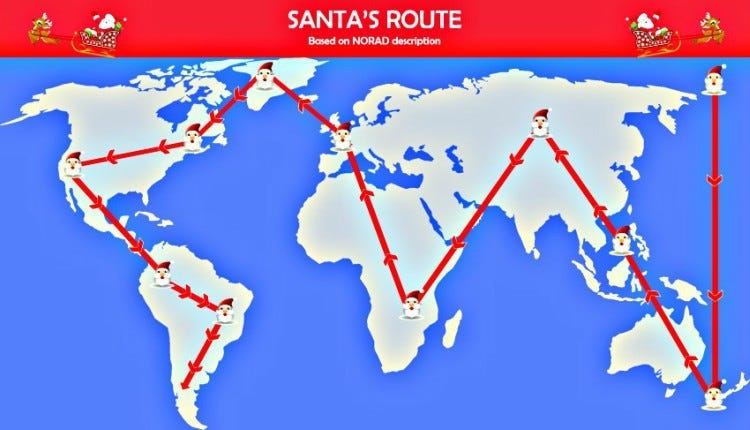

After that I tried looking online to see if anyone had done it already. The best I could find was this blogpost, in which a routing software firm named Paragon maps the description of Satan’s route provided by NORAD – that’s North American Aerospace Defense Command, by the way – and then mocks the way it ignores time zones, before suggesting that Santa might wish to try their software to improve his efficiency.

While I can’t fault the use of festive content marketing opportunities, I can fault the fact they didn’t even bother to make a map of the correct route.

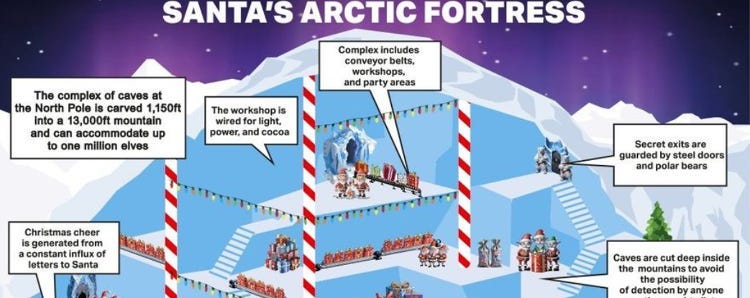

So instead, let us turn to something else entirely, but on which someone did actually make some effort. The writer Séamas O’Reilly will be familiar to many of you, either for his memoir Did Ye Hear Mammy Died? or for his story about accidentally taking ketamine in front of the President of Ireland, Mary McAleese. With the help of pal Michael Murray, and a batshit Times infographic of Osama Bin Laden’s mountain fortress dating from 2001, he’s produced a detailed diagram of “Santa’s Arctic Fortress”. This was a labour of love, done for the benefit of tiny relatives and/or internet clout, so it would be a bit off to steal it for my newsletter, but here’s a carefully curiosity gapped extract:

You can see the whole thing here.

And if that’s still not enough

Some things from New Statesman:

What are the best Christmas sings if you’re very depressed about the world? (2017)

Why Santa has more in common with Batman than the Easter Bunny (2021)

God bless us, every one. x

Once again, attempts to pin down the date more than this seem doomed. Parts of the internet are convinced he died on 6 December 343 specifically, which is lovely, but Encyclopaedia Britannica, which one assumes to have some sort of fact-checking, maintains that it’s impossible to say anything more definite than “4th century”. Terrific.

I wrote that last year. It has since come to my attention that Charlemagne himself was almost certainly ripping off the early Frankish merovingian dynasty that his family had usurped. It is, in other words, turtles all the way down.

These included a Ska band called The Executive. I am trying to imagine a parallel universe in which George Michael was a Ska singer. I am failing in this task.

Many of those people do give a lot of money to charity: it’s just that they often do so in a manner so self-aggrandising as to be wasteful, or worse. Felix Salmon wrote a great piece on this for Reuters in 2012, under the headline “Philanthropy: You’re doing it wrong”, which contains wonderful lines like this: “You kid yourself that your mere presence on the board, or your ‘celebrity endorsement’, is valuable. It’s your money that’s valuable.” You can still read it on the Wayback Machine here.

Why is Christmas specifically on December 25?

Well, there are lots of midwinter festivals - just to pick Roman ones, for it was the Romans who chose the date, there is Saturnalia on 17th December, Sol Invictus on the solstice and the New Year on January 1.

But the predominant pagan midwinter festival in the second and third century, in the period when Christianity was taking off, was Sol Invictus, which was on December 25, the winter solstice. So that was the date chosen for Christmas.

Hold on... but the solstice is on the 21st, isn't it?

It is *now*, yes. The Julian Calendar was designed by the astronomer Sosigenes (of Alexandria) and implemented in (what we now call) 45 BC. In its original form, the solstices and equinoxes were on the 26th of the relevant months. Note that this was a mistake by Sosigenes - the intended solstice and equinox days were Jan 1, Apr 1, Jul 1, Oct 1, so the Kalends of Julius would be Midsummer. Ptolemy pointed out the correction in the first century AD (by which point they had drifted to the 25th) and the date of the festival of Sol Invictus was set based on Ptolemy's calculations.

By the time that the Christian calendar was being set - at the Council of Nicaea in 325AD - the Spring Equinox was now on 21 March, so the Easter calculation ("the Alexandrian computus") was set on that basis. When, in 1582, Pope Gregory, using the work of the astonomers Aloysius Lilius and Christopher Clavius, finally reformed the calendar to get rid of the drift, he dropped ten days from the calendar and this corrected the drift between 325AD and 1582AD, not all the way back to 45BC, meaning our calendar is still five days off from the actual calendar Sosigenes devised and six more from his intended calendar.

This is why we have two midwinter festivals, neither of which is on the actual date of midwinter.

I recently heard, on BBC Radio 4, that the reason for the 1914 football match was that the trenches on both sides suffered rapid flooding, forcing the soldiers to abandon them.