Questions of appetite

This week: some thoughts on the British cuisine debate, some further notes on further Channel Islands, and what the hell’s a primate city?

A question I’ve often wondered about, and which I warn you straight off I won’t be answering, is why there’s no real British cuisine.1 There are numerous individual dishes, of course, from all different corners of this island; but it’s never felt like we have a whole food system in the manner of French or Italian or even German cuisine. Explanations I’ve come across in the wild include the speed of urbanisation during the industrial revolution, the lingering effects of rationing during and after World War II, and “What are you talking about, there’s loads of British cuisine, you pillock”; but I’m not sure any of these entirely answers the question.

Even if I can’t pinpoint the cause, however, I felt comfortable pointing to two related effects. One is that, in contrast to cuisines from many of the world’s other countries, you’re not likely to run into a “British restaurant” anywhere else in the world. The other is that a lot of Americans on social media periodically enjoy taunting the inhabitants of Airstrip One about our terrible, bland food. it doesn’t matter how often anyone points out that tourists are disproportionately likely to end up in tourist traps, that the national dish is curry, or that you can, in most British cities, now find decent food from any one of a dozen major cuisines: no American in history has encountered a single flavour anywhere upon the island of Great Britain, and the entire population of the UK is confidently believed to be so terrified of spices that we all shrivel up, slug like, in the presence of even half a pinch of salt.

In some ways this row serves a useful societal function: this country has depressingly few unifying symbols any more, and since Vera Lynn and the Queen are both dead, fighting with Americans on social media is one of the few things that can still reliably bring us together. The latest incarnation, on up and coming Twitter clone Bluesky last Sunday night, was fun to watch mainly for the parade of left-wing Americans earnestly explaining to a non-white British journalist that only things invented by white people counted as British, apparently under the impression this counted as a progressive position, somehow. Other than that, though, it was the exact same row that plays out so often we might as well set a recurring event in our national phone calendar.

It did get me thinking, though, about why this schtick is so irritating – so much so that we do, as a national community, rise to it basically every time. One reason, I think, is that you can be the best sport in the world and still find your hackles rising when confronted with the same joke for literally the ten thousandth time. One Monday morning a few years back, I accidentally published some pictures of trains which I hadn’t realised, in my rush to leave the office the previous Friday night, were models, and found myself mocked on multiple continents. Fair enough: I’d made an arse of myself, and took my punishment in good spirit. A few months (literally: months) in, though, I still found myself snapping at strangers that, for god’s sake, could they not at least come up with some new material.

So that’s part of it. But it’s also frustrating, I think, to be periodically reminded that literally everyone still sees attacking your noticeably declining country as punching up. It’s one thing to be accused of having bad food, and having got what decent stuff we have through imperial adventurism, by, say, a Bangladeshi. Facing the same accusations from a resident of a superpower – one which, incidentally, stole a third of its land from Mexico in an imperialist war – is quite supremely irritating. At a point in history when it feels unnervingly plausible that Britain is at risk of disproving the widespread assumption that rich countries always stay rich, it feels, despite the many crimes of the imperial past, mean.

Fish and chips, incidentally – one of the dishes which often features on the list of British crimes against American taste buds – was also not an indigenous invention, but arrived with sephardic Jewish immigrants in the 18th and 19th centuries. Anyone who thinks that counts as British, while curries invented in Birmingham, Bradford or Glasgow do not, might usefully wonder what they’re accidentally telling us about their view of the world.

Well, this is unexpected

A thing you need to understand about me is that I am never early for anything. I went to embarrassingly few lectures during my degree because they foolishly held them in the morning. When I make friends come to my local, they always get there first. I was literally born two weeks later than I was supposed to be.

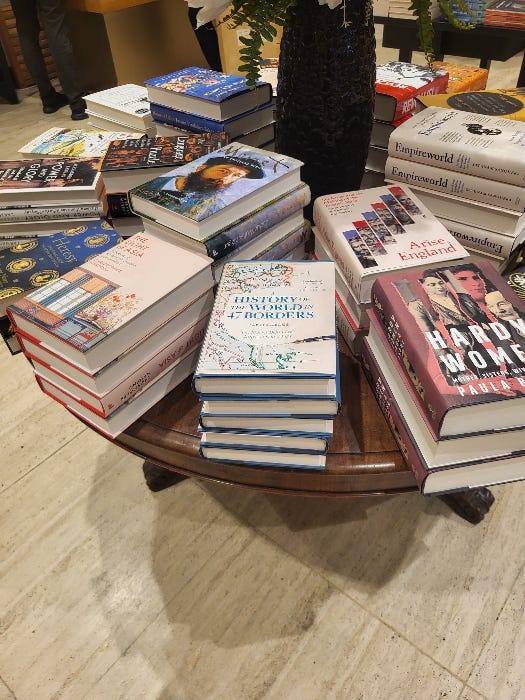

And yet, as of late last week, my sources began informing me that A History of the World in 47 Borders: The Stories Behind the Lines on Our Maps was beginning to appear in shops and in letterboxes the better part of three weeks early. On Saturday I went out looking for it myself, and found it in multiple places, including the big Waterstones on Piccadilly…

…and Foyles, where it was pleasingly shelved directly above the latest work from a man who once wrote an article for a magazine I edited, and filed it longhand and by fax.

Anyway: it’s out! if you want the audiobook or ebook, alas, you’ll have to wait for the official publication date, which remains Thursday 25th. Those of you who want hard copies, though, can march into a shop and get it right now.

On Sunday, by the way, a friend sent me a picture of that same table in Waterstones Piccadilly. I felt genuinely quite emotional when I saw that the number of copies of my book on it had gone down.

If you have bought the book, I really hope you like it. I think it might be the best thing I’ve ever done.

Bonus content! My lovely former New Statesman colleague Patrick Maguire was kind enough to have me on his occasional Times Radio show for half an hour on Friday to talk about borders. You can, and should, listen to it here.

Some notes on primates (not those ones)

Lost down some wiki hole or another the other day, I came across a term I’d not encountered before: Bangkok was, I learned, “a primate city”. At first this brought to mind the sort of thing you’d get on Planet of the Apes2; then some kind of conclave of senior bishops.

But no. A primate city, I learned, was one that is by far the biggest and most important in its country/state/region/whatever. In some ways it was surprising I’d never stumbled across this term before – partly because I edited a website about cities for six years, but mostly because I’d observed the phenomenon before and long thought the presence or otherwise of such a city has quite a big impact on what kind of a country you are. I just didn’t know there was a name for it.

Let’s start with the definition. The geographer Mark Jefferson, who coined the term in 1939, defined it as being “at least twice as large as the next largest city and more than twice as significant”: today, though, it’s generally taken to mean one that’s disproportionately larger and more important than its nearest rival. London and Paris, which are vastly bigger than Manchester or Birmingham/Marseille or Lyon, are primate cities; New York is not, even though it’s huge, because although Los Angeles is smaller and less important, it isn’t that much smaller and less important. The same applies to the relationship between Beijing and Shanghai, or Sydney and Melbourne.

Here’s a map: countries in grey have a primate city; those in red do not.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.