Rishi Sunak is no Taylor Swift

This week: Rishi Sunak continues to fade away; some notes on Time Magazine’s Person of the Year award; and a crossrail for Glasgow.

For my New Statesman column last week, I wrote about the visible manner in which Rishi Sunak’s authority was draining away, using, as my way in, the manner in which his “nothing has changed” press conference was unnervingly reminiscent of those Theresa May called every 20 minutes or so back in 2018. Power, I wrote, is not something “mechanistic, which flows automatically from possession of title or position... It’s an illusion, a parlour trick, in which leaders have power because we imagine that they do, and expect the world to act accordingly.”

It’s tempting to wonder, the morning after The Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill passed its first vote in the Commons, if I called this wrong. For all the talk of how the Prime Minister was under siege simultaneously from both wings of his party, in the event not a single Tory MP voted against the Bill. Even the most enthusiastically anti-reality factions of the right – who have taken, delightfully, to calling themselves “the Five Families” as if they’re people like Tony Soprano, rather than people like Mark Francois – merely abstained. There will be no leadership challenge, let alone an election. Sunak lives to fight another day.

Any prime minister who is tempted to start thinking this way, however, will be swiftly disabused by a look at today’s papers. Several have headlines ending, ominously, in “for now”; the Mirror warns of “the Nightmare After Christmas”. Sunak has won over neither those who think the bill goes too far in undermining national law, nor those who think it does not go far enough: he’s merely persuaded the latter group to abstain by promising to toughen it up in the New Year. Doing that, though, would surely alienate those One Nation Tories (these apparently still exist) who voted for it, despite their concerns, this time round. The underlying political problem – that it’s not clear that there is a version of this bill that wins support from enough Tories to assemble a Commons majority – remains.1 He’s merely kicked the can down the road.

All this, just like that press conference, is more than a little reminiscent of 2018-9. Back then there was no version of Brexit that could assemble a majority in the House of Commons: May’s signature move was instead, each time, to find the compromise that would keep the show on the road, never missing an opportunity to store up problems for tomorrow if it saved her bacon today. It finished her, in the end; but it took a surprisingly long time.

All of which is a long way of saying that this victory means nothing: Rishi Sunak is still a lame duck Prime Minister, whose authority over his party, let alone the country, is already exhausted. But May hung on for months after her career was clearly over, and the next election needs to be called in the next 364 days. Let’s not kid ourselves that the Prime Minister can’t hang on that long. Or, given the state of the polls, that he won’t.

Some utter shamelessness

This is just a quick reminder, as the season of goodwill and panicked gift buying approaches, that I have not one but two books available. Conspiracy: A History of B*llocks Theories and How Not To Fall For Them, co-written with the gorgeous Tom Phillips, is exactly what it sounds like: a history of conspiracism, with explanations for why we are all, if we’re honest, prone to it, with jokes. (Only this week, Oliver Webb-Carter from the Aspects of History podcast described it as the ideal stocking filler.)

There’s also The Compendium of (Not Quite) Everything, which is a book of facts, lists and observations, from the Big Bang and the creation of the Universe to some theories on the afterlife and famous last words. It’s been described as perfect for the curious child/curious dad/really anyone in your life by no less an authority than its writer, me.

Right, that’s enough advertising, back to the content.

Some notes on the Time Person of the Year

Last week certain bits of the internet which I have vowed never, ever to cross got very excited because Time magazine had named Taylor Swift as its person of the year. This was seen, best I can tell from my ageing male perspective, as broadly a positive and exciting thing for the Swifties.

And, as it happens, it broadly was. Swift was the first artistic figure to attain that exalted status, and the first woman to be recognised more than once (sort of; I’ll explain below). But she was not just being recognised for her cultural achievement, but her economic one: the Eras tour is now the highest grossing concert tour of all time, and has had enough spillover effects on the cities it’s visited that it’s been credited with the Federal Reserve for boosting the US economy, and led the Wall Street Journal to coin the term “Taylornomics”.

Being Time’s Person of the Year isn’t necessarily positive, however. The magazine awards the accolade to the person who “for better or for worse... has done most to influence the events of that year”: 1938’s award did not go to Adolf Hitler because of Time’s support for Anschluss or the occupation of the Sudetenland. Still, it’s nice to have an answer to the question “why is Taylor Swift like Adolf Hitler” at long last.

I toyed with running a complete list of winners, accompanied by my commentary, but swiftly (yes) realised that a) you could find that on Wikipedia and b) doing a single sentence on every winner since 1927 would go way over my word count. So instead, some observations.

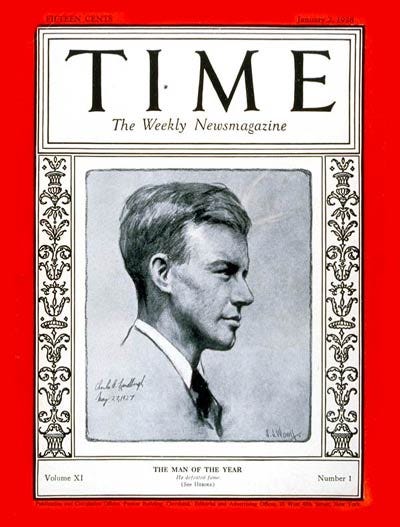

1. The first Time Man of the year was Charles Lindbergh. On the one hand, he’d recently completed the first solo transatlantic flight when he flew the Spirit of St Louise from Garden City, New York to Paris. On the other hand, he would spend the rest of his career dogged by rumours of anti-semitism and Nazi sympathies. (The 2004 Philip Roth novel The Plot Against America imagines the persecution of Jews conducted by a Lindbergh White House.) Pleasingly, this means that the morally ambivalent nature of the award was there from the very start.

2. You’ll notice I said “Man of the Year”, not “Person of the Year”. That’s because, for most of its history, that’s what it was: on a few occasions (Wallis Simpson in 1936; Elizabeth II in 1952; Filipino president Corazon Aquino in 1986) it had been “Woman of the Year”. In 1937, the magazine selected Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Soong Mei-link as “Man and Wife of the year”; in 1975, it recognised “American Women” as a group. (Girl power!)

Most years, though “man” was sufficient. It was only in 1999 that anyone got around to thinking, “Hmm, is this whole gendered thing a bit iffy?”

The first person of the year, incidentally, was Jeff Bezos. Like I said: Girl Power.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.