Some great (awful) fires

There was a *second* great fire of London? Huh.

Quick note before we begin: this is your last chance to get 5% off an annual sub and a free paperback of my (Sunday Times bestselling!) book, A History of the World in 47 Borders. In all honesty, I meant to close this offer weeks ago and keep forgetting, which means periodically realising I need to order more books and feeling very slightly annoyed about it.

Anyway, I’ll keep it open til Monday, ish. Get in while you can:

Enough of that. This went to paying subs back in February.

The Great Fire of Rome (18 July 64CE)

Probably the origin of the idea of a “great fire” (incendium magnum). Started in the shops around the Circus Maximus, then, thanks to strong July winds, spread the whole length of that chariot stadium and well beyond. Destroyed 70% of the city, and killed hundreds.

The emperor, Nero, blamed Christians; everyone else blamed Nero. Actually probably an accident. Fires in Rome happened all the time: if you crammed over a million people into that small a space, it was inevitable that one would spread eventually.

After the fire, debris was used to fill in malarial marshes nearby, while Nero introduced new rules which increased the width of streets to make a recurrence less likely. He probably didn’t fiddle while Rome burned, however. Suetonius has him weeping and watching the city burn from atop the city walls; Dio Cassius has him dressed as a player of the cithara, a sort of lute. All this feels like the sort of post hoc briefing that a lot of emperors who were later assassinated, requiring post hoc justifications, got stiffed with.

Before you feel too warmly towards the guy, though, he also built himself a massive palace on the land the fire cleared, so.1

The Great Fire of London (2-6 September 1666)

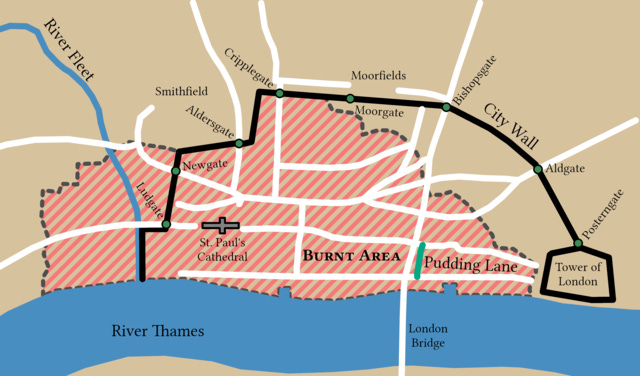

Famously started in Farriner’s Bakery on Pudding Lane, not far from the Monument – that’s why it’s there – just after midnight. By far the most effective way of fighting major fires at the time was to demolish anything standing in its way – sucks if it’s your house, but then again at that point you’re probably stuffed anyway. But the Lord Mayor dithered, and the fire grew large enough to create a firestorm – its own wind system! – so by the time he made up his mind it was too late. Ultimately destroyed Old St Paul’s and, after jumping the River Fleet, came close to knocking out the royal palace at Whitehall, too.

Only a handful of deaths – as few as eight – were officially recorded; but some historians have raised an eyebrow, and suggested that the fire may have burned hot enough to kill a far higher number of the undocumented poor without trace. French and Dutch immigrants faced street violence, too (people just love to scapegoat the foreigners!), and Charles II encouraged the dispossessed to move elsewhere. Grand rebuilding plans came to nought, however: beneath its skyscrapers, the City retains much of its medieval street plan.

Pudding Lane would later become one of the world’s first one-way streets – but we can probably assume this to be a coincidence.

The Great New Orleans Fire of 1788 (21 March)

Destroyed more than three quarters of the buildings in the main port of Louisiana, a province of what was then, slightly unexpectedly, “New Spain”. (The French had secretly handed it over at the end of the Seven Years’ War, a quarter of a century earlier.) It was a deeply Catholic city, and because the conflagration began on Good Friday the priests refused to use church bells as a fire alarm, which worked out brilliantly. They probably felt pretty stupid, though possibly not as stupid as the boys playing with flint and tinder who managed to start...

The Great New Orleans Fire of 1794 (8 December)

Oh, no.

Destroyed several of the blocks that had only just been rebuilt. You’d feel like a right twat, wouldn’t you? Anyway, this is why there’s so much unexpected colonial Spanish architecture in a previously francophone city in an English-speaking country.

The three Great Fires of New York

On 21 September 1776, when the city was occupied by British forces thanks to the Revolutionary War, a fire destroyed several hundred structures – at least a tenth and possibly a quarter of the city. Both sides suspected arson.

Less than six decades later, it happened again. On the night of 16 December 1835, a fire broke out in a warehouse off Wall Street. The resulting fire consumed 17 blocks, killed two and was visible 80 miles away in Philadelphia.

And less than 10 years after that, on 19 July 1845, it happened again. This time it began in a whale oil and candle factory – you see the problem? – then spread to a warehouse full of saltpeter which promptly exploded. Destroyed hundreds of buildings and killed around 30.

Two conclusions: the tag “great fire” is used a lot more freely than I’d imagined it to be; and wooden buildings are a great enough fire risk to render arson unnecessary, however suspicious the timing.

The Great Fire of 1805 (11 June, Detroit)

Motown insisting on being different by making the name of the fire the year, not the city. This may actually be because, in 1805, there wasn’t really a city – the settlement was only home to a few hundred people, making it little more than a village – but the fire, another which probably started in a baker’s shop, was kind of a big deal, destroying almost everything except one warehouse and one military fort on a hill.

On the upside, no one died, and the event did give the city its motto: Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus (“We hope for better things; it will rise from the ashes”).

The Great Fire of Edinburgh (15-19 November 1824)

Lasted five days, destroyed 400 homes, killed 13. Broke out in an engraving worship in Old Assembly Close, just off the High Street – but the Old Town of Edinburgh is full of tightly packed buildings divided by narrow alleyways, and the fire quickly spread, aided by the wind.

The city had a permanent fire brigade, but it was very new – had existed for all of two months – so was still finding its feet and more to the point the water supply. And so, the blaze continued to spread, destroying the Old Assembly Hall in the night. The worst day, though, seems to have been Tuesday 16 November, when the spire on the Tron Kirk – a 17th century church, which still overlooks the city today – caught light and molten lead began to pour from its roof. Later that night, a second blaze began on an 11-storey building on Cowgate – this, by the way, before anyone had invented passenger lifts – leading to panic about both arson and the wrath of god. (Embers were the more likely culprit.)

An inquiry was held into the fire, but exonerated James Braidwood, the master of the fire brigade, which is why there is still a statue of him in the city’s Parliament Square today.

The Great Chicago Fire (8-10 October 1871)

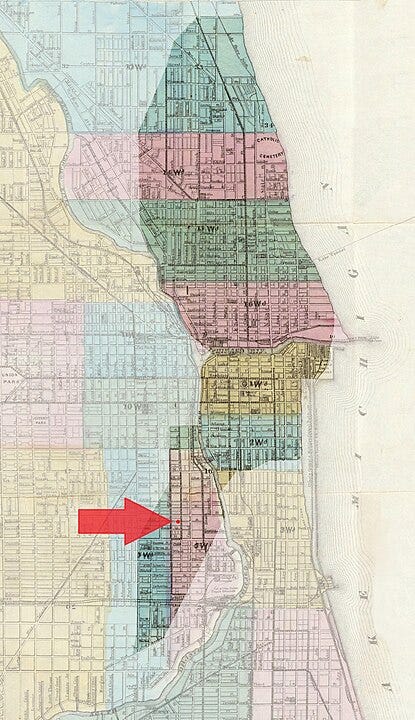

Puts Edinburgh into perspective. Began in a barn on DeKoven Street on the near west side; spread fast due to hot, dry, windy conditions and a city made primarily of wood. (Chicago’s population had grown by a factor of more than 60 – that isn’t a typo – in a single generation.) Most unnervingly of all, the fire crossed the Chicago River at least twice.

Destroyed nearly 9 square kilometres of the city – over 17,000 buildings, worth an estimated $222m (nearly $6bn today), and left over 100,000 people homeless. Also killed 300. Did at least lead to improved building codes, so that’s something.

The Second Great Fire of London (29-30 December 1940)

I hadn’t actually heard the term until I started researching this piece. As you can probably guess from the date, the culprits this time weren’t bakers but the Luftwaffe.

Anyway, this one involved more than 100,000 bombs, killed 163 and destroyed an area larger than its predecessor. It also destroyed the Guildhall’s Great Hall, and damaged the dome of St Paul’s, too. The phrase comes from an American news reporter, wiring copy home.

There are loads more: Stockholm, Toronto, Hamburg, Bucharest. An unnerving number of them, it must be said, concern relatively small English towns like Bedford and Wymondham, not all of which get their own page, which leads me to suspect that:

a) the phrase a “Great Fire of” is a sort of meme, a label people tend to attach to any sizable fire because they already know of examples in other cities, and…

b) Wikipedia may be fuelling this, adding the label to incidents which may not previously have used it, possibly because…

c) a lot of its most active editors are based in small English towns.

The most important of the moment, surely, is:

The Great Fire of Los Angeles (2025)

The brain works in mysterious ways. I’ve had this idea on my list for a while, and it’s only when I came to write it that I understood the reasons for my sudden sense of urgency.

Anyway, whether the name will catch on remains to be seen. Steve Schmidt – a one-time Republican political operative, who worked with George W. Bush and John McCain, but seems sincere in his disgust at Trumpism – did describe last winter’s events as such on his Substack, but trying to evaluate the historic importance of an event while it’s still going on is madness.

It is definitely, however, big: at least 29 dead, at least 18,000 buildings destroyed, more than 200,000 evacuated, estimates of financial losses upwards of a frankly unimaginable $250bn. “The worst case scenario has arrived,” Schmidt adds, “and don’t let anyone tell you that it was unforeseeable.”

If this particular fire were to remind American billionaires that, however rich they are, they still share the same physical vulnerabilities – to climate change; to natural disaster – as the rest of us, then it could be the most consequential of any of the fires I’ve listed. But, well, would you bet your house on it?

A reminder, as ever, that this newsletter is, and will always remain, needs-blind. If you want to read but, for whatever reason, can’t currently afford it, you can just hit reply and ask and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. In contrast to the British state, I’d far rather accept the risk of a few people ripping me off than of those in genuine need going without.

But if you *can* afford it, I’d really like it if you

Conspiracists say this may have in fact been a motive for the fire, but they’re probably wrong: the thing about being emperor was you didn’t really need an excuse to take other people’s stuff.