Some notes on continental divides

Actually existing natural borders.

A few months ago I had the privilege of reading a book that hadn’t been published yet1: This Way Up, the debut from YouTube’s Map Men Jay Foreman and Mark Cooper-Jones. I thought mentioning it here might be doing them a favour in the old publicity stakes; but then I saw their Amazon ranking and realised those guys didn’t need my help and I’d just lost the Christmas market. Shit shit shit shit shit.

Anyway, where was I? Oh yes, the book is extremely good and you will all like it. But! The reason I am using it as a drop intro is that one of the stories contained therein started me thinking.

The story in question involves the Donner Party, a group who in 1846-7 made the rookie error of trying to take a shortcut when crossing North America before anyone had built any roads or railways, let alone motels or 7-Elevens. That chapter (which is lots of fun, by the way; you really will enjoy the book!) includes a reference to the point they crossed the Great continental divide – the notional line that marks the United States’ main hydrological divide. Pour a glass of water out almost anywhere on the eastern side of the line, and it will flow, eventually – it will take some time, and possibly a lengthy diversion via a smaller sea – into the Atlantic. Pour it out on the other side of that line, and it will flow, probably rather more speedily, to the Pacific.

The reason for the difference in timescales is that the continental divide doesn’t actually run down the middle of the continent, or anything like. It’s some way to the west, following the line of the Rocky Mountains: for the vast majority of the US and much of Canada, water will flow, eventually, eastwards.

Why the Rockies should form part of the divide is self explanatory – water is not famous for flowing uphill. But isn’t there another sizeable mountain chain in the eastern United States? Why doesn’t that pose a similar barrier?

Actually it does. Here comes the map:

The Great continental divide, which follows the Rockies, is in red. The Eastern divide, which follows the Appalachians, is in orange. In between those two – an area accounting for what looks, at a glance, like more than half of the lower 48 states – water doesn’t flow directly to the Atlantic, but towards the Mississippi River system, and thus the Gulf of Mexico. That Gulf, though, is still a marginal sea of the Atlantic – and so, hydrologically, this is still considered to be eastern North America.

North America, of course, is actually surrounded by three oceans – so further north, things get more complicated. In eastern North America, beyond the Laurentian Divide (in green), water will end up in the Arctic Ocean, whether via Hudson Bay (to the south of the blue line) or the Beaufort Sea (to the north). Raindrops falling on the point where the Great Continental and Laurentian Divides meet – the aptly named Triple Divide Peak in Glacier National Park, Montana – can be separated by inches, and yet end up in three completely different oceans. How cool is that?2

Oh, also – look closely at the Laurentian divide and you will notice it divides both North Dakota and Minnesota. That means that there is a part of the eastern United States that does not drain into the Atlantic, but into the Arctic, which is why there was a slightly awkward “almost” above.

A couple of other things worth nothing about this map. One is what’s going on with the loops within the Great Continental Divide, or indeed the enclosed area in brown (the Great Basin Divide). These are endorheic basins – areas of ground from which water will never reach an ocean at all. Instead, it’ll either drain into lakes and swamps and then evaporate, or merely evaporate without going anywhere much at all. Such lakes can be huge – the Caspian Sea, the world’s largest inland body of water, an area as big as Japan, is one – but they don’t get any bigger because the water flowing in is balanced by the water evaporating out.

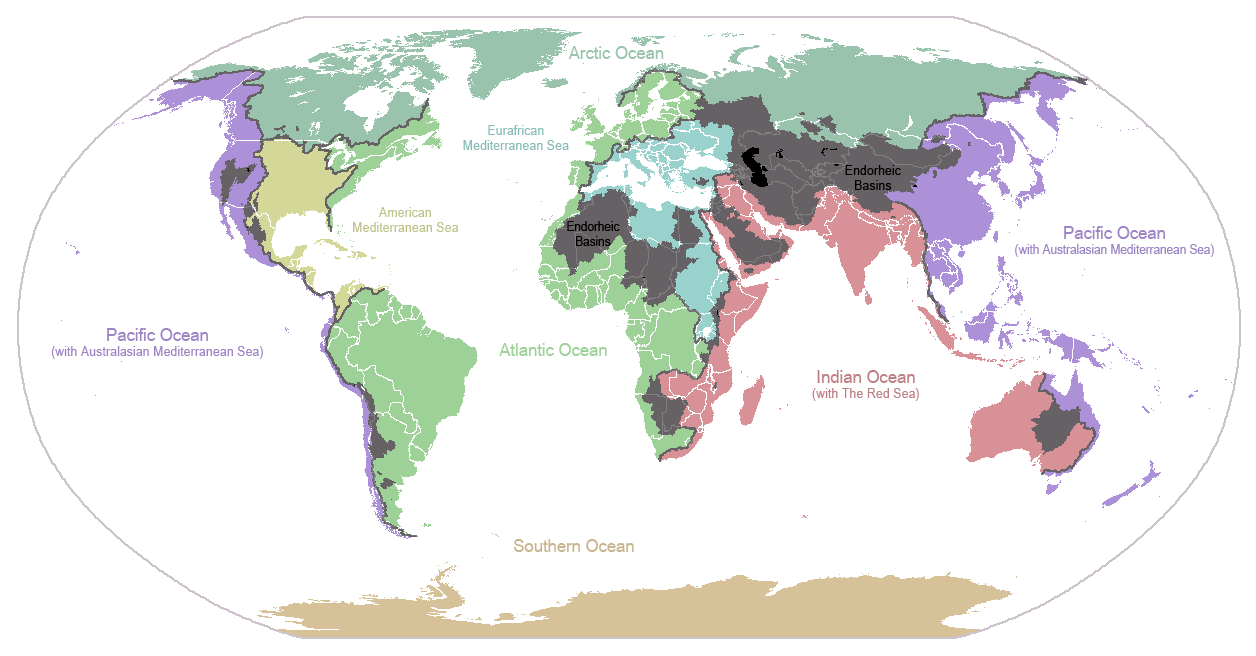

Surprisingly huge swathes of the globe are covered by such basins, in fact. Check out this map of the world’s continental divides, with endorheic basins in grey and major endorheic lakes in black:

Another point, highlighted by that same map, is that continental divides need not be remotely as dramatic as the Rocky Mountains. Indeed, the highest peaks don’t need to be on a divide at all, providing there is a way around them. Because a continental divide needs to be a continuous line, the key thing is not the height of the peaks, but the height of the passes between them.

That said, a really big mountain chain does help. The Great Continental Divide doesn’t stop at the US southern border, but continues through Mexico and Central America all the way to the Andes. And if you thought North America was unbalanced hydrologically, check out its southern neighbour:

An explanation, if one were needed, for the existence of Chile.

If you enjoyed that and would like to read more things by me but can’t afford a subscription, just hit reply and ask: I will say yes, no questions asked. If you can afford one, though, you know the drill:

Go on, it’ll make me feel warm and fuzzy when I’m trying to stay motivated to finish a book.

To give them a cover quote. I hope you enjoy the array of quotes from actually famous people, with whom it is assumed you will be familiar, plus my name followed by a lengthy explanation of who I am and why anyone should care what I think.

The area around the peak, incidentally, attempts to brand itself to tourists as the “crown of the continent”.