This week’s dip into the archives…

Back in the early 1990s, my grandfather liked to record improving documentaries for me, little realising the outsized influence he’d thus have on the sort of things I’d be writing decades later. One of them was a BBC documentary strand, concerning the history of measurement. It had four episodes (length, weight, temperature, time). It had linking narration from a northern actor who I’m moderately confident was Brian Glover. It had a silent actor playing a character called “Mr Measure”, who acted out various measurement-y things, and clips of minor celebrities like Prue Leith, talking about how she’d once got some measurements wrong and thus ruined a cake. The reason I am being a bit vague about all this is because the people who’d made it had given it the title Measure for Measure, a Shakespeare play the BBC would adapt in 1994, and thus made it all but impossible to find information about on the internet of 2024.

I loved these documentaries. I watched them again and again, learning a lot about the history of length and weight and so on in the process, and I was devastated when a friend with access to the BBC archive leaked me some copies a couple of years ago and it turned out that the memory cheats and they weren’t actually very good. Oh well.

It does mean, however, that I have been interested in questions about why the metre is a metre and where we got pounds and ounces from for much of my life, and included a couple of entries about such topics in my book The Compendium of (Not Quite) Everything. It also means that I was hugely excited to read Beyond Measure: James Vincent’s 2022 book on the history of metrology.1 The reason that book is so great is that it’s not just about the history of how we measure weight and length and everything else. It’s also, in a way I wasn’t expecting, a sort of history of philosophy, too; of how the human species has seen the world.

You should all read that book ASAP – honestly, you’d love it – but to give you a flavour, here are some of the things I learned from it that still stay with me.

1) The Ancient Egyptians used “Nilometers” for their economic forecasting.

Egypt, Herodotus fans will remember, is “the gift of the Nile”: the kingdom’s wealth and prosperity came from the fertility of the Nile valley, which resulted in turn from the annual flooding during Akhet, the “season of Inundation”, which ran from roughly September to January. (The other two seasons were Prt, or emergence, January to May; and Shemu, or harvest, May to September.)

The bounty of the harvest, though, depended on the level of the flooding, which is where the nilometers come into it. Each is a structure – a column, a well, a stairwell – with markings in the stone to measure the depth of the neighbouring river, and thus make economic forecasts about the year ahead. In the period of Roman rule, Plimy noted that, “When the water rises to only 12 cubits”, the country experiences “the horrors of famine”. An increase of sixteen, though, is “productive of unbounded transports of joy.”

2) Measurements used to change depending on context.

Medieval European societies, for example, tended to measure land not in absolute area but in how long it would take to plough: the Italian gionarta, French journal and Germanic tagwerk all reflect the amount of land you could plough in a day, which meant that the units would shrink in areas with harder soil or uneven land. “As a result,” James writes, “the act of measuring encoded geographical and agricultural information relevant to workers.”

The Germanic morgen, reflecting the area it’d take a single morning to plough, was incidentally two-thirds the size of the tagwerg: a sign perhaps of how medieval peasants were more productive in the mornings, too.

Talking of flexible measures:

3) The Finns had a measure for the farthest distance at which you can hear a dog’s bark.

Before easy access to measuring equipment, James argues, societies developed measurements using the human body or other natural phenomena you could rely on having to hand. One was the Finnish peninkulma, which translates as “dog’s hearing”: around 6km, although when Finland adopted the metric system in 1880 they redefined it as 10km.

This too, though, was a flexible measurement, changing depending on whether terrain is flat or hilly, open or wooded. (It’s clearly lower in a city, which is good, because Henry Scampi still insists on replying to any barks he happens to hear, just in case it’s a potential friend, and there must be literally thousands of dogs within 10km of my flat.) “But this flexibility offers its own store of information, giving some indication of terrain and accessibility.”

4) The French Revolution happened partly because of fury about measurements.

By the late 18th century, France could boast over 1,000 different measures with a ludicrous 250,000 different values: some, like the pinte, could vary by more than a factor of three, depending on where in the country you were.

This didn’t work out brilliantly for, well, anyone. Peasants were annoyed they were paying taxes in a measure that could change on the whims of the tax collector; those higher up the social scale were worried about its impact on economic development. As a result, in the Cahiers de doléances, a list of grievances compiled by the Third Estate2 immediately prior to the revolution in 1789, inconstant measurements appear more frequently than matters concerning personal liberties or the court system. This isn’t that surprising: there’s a lot of this stuff in Magna Carta, too.

5) The metre is the wrong length.

One of the results of the Revolution – perhaps its most enduring – is the metric system, which is now the world’s most popular system of measurement, even if the French themselves rejected it for some years.

Creating that system, though, required the revolutionaries to determine entirely new measures for length (the metre) and weight (the grave, or kilogram as we know it today). The latter was defined with respect to the former – it’s the mass of a litre of water; the litre, in turn, is a cube 10cm on either side – so on the whole defining how long a metre should be was pretty important.

The best way of doing this, it was decided, would be to make it 1/10,000,000th of the quarter meridian, the distance from the equator to the North Pole. To find out how long that was, from 1792 to 1798, a pair of surveyors, Jean-Baptiste Delambre and Pierre Méchain, were sent to measure a line from Dunkirk to Barcelona, which they could then use to calculate the rest. Along the way, they almost got murdered by angry locals convinced they were something to do with the tax system.

A pity, then, that it turned out that the entire premise of the mission was misguided, because the Earth isn’t a perfect sphere. Oh, and also Méchain messed up some measurements and was so mortified about it that he didn’t tell anyone for the rest of his life.

So the metre they ended up with – which would soon exist as an actual physical object, in a museum in Paris – is, y’know, fine. It just isn’t actually the length they claimed to be calculating.

6) The kilogram has been losing weight.

The metre isn’t the only metric measure which still exists as a physical object today. From 1889, the mass of the kilogram was defined by the International Prototype Kilogram – “Le Grand K”, a 90% platinum/10% iridium cylinder, 39mm in both diameter and height, sitting in a vault in Paris. The International Bureau of Weights and Measures – known by its French acronym, BIPM – also has six sister cylinders; official copies were sent to other countries to provide their reference kilograms, too.

Le Grand K is pretty important, since it underpinned three of the other SI base units, the building blocks of the metric system – in this case, the mole (a measure of the amount of substance), ampere (electric current) and candela (brightness). It was an issue, then, that by the end of the 20th century, the cylinder was found to be losing weight. Not much – 50 micrograms, or 1/200th of a gram – but when you’re talking about the reference point for the entire world’s system of measurement, any change is a problem.

So, in 2019, Le Grand K was retired, in favour of a new definition of the kilogram based on Planck’s constant, a fundamental constant of the universe. It was attending the ceremony where this officially took place, incidentally, that inspired James to write the book.

7) The commonly held idea that you should walk 10,000 steps every day is a fluke of the Japanese writing system.

It was invented by the marketing campaign for an early pedometer, in the run up to the Tokyo Olympics of 1964. Why 10,000 steps? Because the Japanese character for 10,000 – 万 – looks a bit like someone walking, and this made for a nifty bit of branding.

You should still do it, though, if you can. Walking is good for you.

Beyond Measure: The Hidden History of Measurement by James Vincent is out now. Honestly, you won’t regret it.

Dog/sales pitch/etc

So, two things:

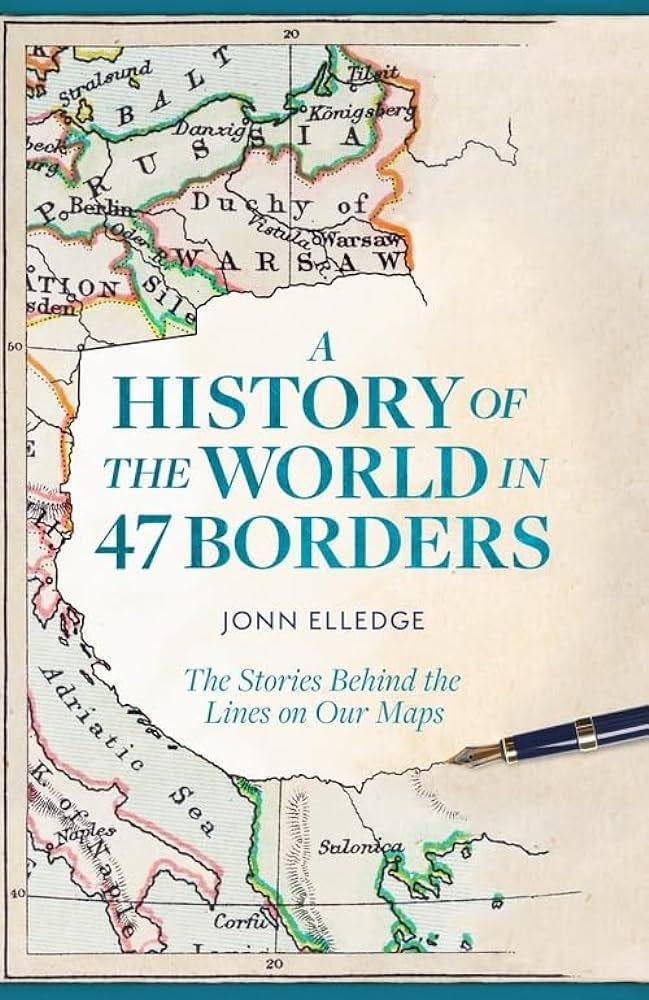

1) My new book is out in just two months, and the latest person to say something heart-meltingly wonderful about it is the Guardian’s Marina Hyde: “Totally fascinating and hugely entertaining... Jonn Elledge has such a gift for looking at complicated bits of the world, then telling you all about them in a way that feels not like a textbook, but like an incredibly fun and interesting conversation in the pub.” As you probably know, because I never shut up about it, pre-orders really help with visibility later on so please, you know what to do

2) If you’d like to read stuff like the essay above when I write it, rather than when I deign to release it from the paywall and sometimes not even then, my rates are very reasonable. For just £4 a month, or £40 a year, you can get a weekly dose of politics, maps and nerdery like the above, plus some diverting links, and help ensure Henry Scampi has enough energy to be excited at strangers.

But it gets better! Here’s a special offer: 30% off if you sign up for a year!

Alternatively, as ever, if you want to read the newsletter but for whatever reason can’t justify the money right now, just hit reply and ask. I always say yes because I am lovely.

Well, technically, James read it to me; not because he’s a friend, although he is, but because I’m a huge fan of technologies that allow people to read their books to me while I’m walking about.

Those who were neither nobles nor churchmen.