I have retreated to my comfort zone in my TV viewing of late. Often that means Doctor Who or Star Trek, or at least, something that reminds me of Doctor Who or Star Trek. (The Orville, against all the odds, and despite both its a showrunner and its lead actor being the guy who created and played Brian the Dog, is actually really good?)

Sometimes, though, it means revisiting the TV comedy of my youth. Andrew Marshall’s 2 Point 4 Children ran from 1991 until 1999, which means it overlapped my “obsessively watching BBC sitcoms” phase almost perfectly. Its set up was ostensibly that of the classic family sitcom (two kids, a girl and a boy, hapless dad, funny neighbour). What made it great, though – besides the vast numbers of references, the occasional musical number and its increasingly frequent descents into surrealism – was the way the mum, Belinda Lang’s Bill, wasn’t the long-suffering, sensible one: she was allowed to be just as ridiculous as anyone else in the show.

Exhibit A. Image: BBC.

I loved this as a kid, and it’s all on iPlayer, so I’ve been rewatching it and pretending to myself I haven’t noticed the way the main actors are now all younger than I am, when suddenly I spotted a street sign just down the road from the Porters’ family home: “Devonshire Passage”. That identifies the street the house is on as Duke Road, which lies between Chiswick High Road and Hogarth Lane. That, one quick trip to Rightmove later, enabled me to learn that the average price of a house on the Porters’ street is now £1.4m.

In the world of the show, the Porters are a plumber and a caterer; both are self-employed. I’m not saying the world it depicts is unrealistic – there have been plenty of stories about how plumbers actually earn a fortune (though on googling it’s at least possible this is, at the very least, overdone), and anyway, the characters seem to have been in their home since the 1970s. Terraced houses in Chiswick were not going for £1.4m during the Callaghan administration.

But such a family would be extremely unlikely to live in such a home now, for reasons I no more need to spell out than I do why I’m in the market for comforting evening viewing. It’s a bog standard, unexciting family home, not a palace; but its price is completely out of reach to anyone who isn’t already loaded. An attempt to make that sitcom about that family in that location today would be about as realistic as, well, all that TV scifi I could be watching instead.

This is a common problem for TV, and has been so for a while. One of the earliest bits I ever wrote as a regular contributor to the New Statesman, back in November 2013, had the headline, “If art really imitated life, no one in Eastenders could afford to live in Albert Square”. In it, I wrote about the house in Outnumbered, another family sitcom about a couple who worry about money and do unspectacular clerical jobs, yet live in a London home with at least four bedrooms over three floors. Nine years ago, I calculated that their house must be worth at least £1.1m. In 2020, it actually went on the market for £1.7m, an increase of over 50% in just seven years.

The price of other TV homes are only marginally less silly. A 2-bedroom flat in Croydon, of the sort the leads occupy in Peep Show, would have then set you back around £175,000; now anything under £250,000 looks like a bargain, and some optimistic property developers are trying to sell luxury flats in this patch of suburbia for three times that. Two-bed flats in London N7, of the sort which provides the setting for Spaced, would set you back around £600,000 today. Meanwhile, you’d be lucky to find the sorts of homes you’d get on Eastenders’ Albert Square for anything much less than £900,000; many of the options seem barely cheaper than those in Chiswick.

This is bad, of course, but is it just a London problem? Yes and no. It’s certainly at its worst in London, as most things involving housing are. That doesn’t mean things elsewhere are good, however. In 2017, the online estate agency eMoov (geddit?) had a minor viral marketing hit when it put out a press release looking at property prices in various TV soaps. It found that a home on Coronation Street would have then cost around £143,000, a detached home in Emmerdale would have cost £334,000 and so on. I’m not altogether sure about this research, since it seems to be under the impression that Hollyoaks is set in Liverpool (Chester, surely?), but it’s the best I’ve got for working out house prices in fictional places so I’m going with it.

How much would those homes cost now? Well, house prices in Manchester have climbed by around 28% in the last five years: that would put a home on Coronation Street at around £183,000. Those in a non-existent bit of Yorkshire are harder to calculate, and a detached house on a farm is hardly representative anyway; but county-wide they seem to have climbed by around 15-20%, so just for the record, the one on Emmerdale is getting uncomfortably close to £400,000. Up the road in south Liverpool, the sort of terraced houses that provided the setting for Bread – another long-dead sitcom, whose focus on never having quite enough money was literally written into the name of the show – now seem to be on the market for £200-300k.

These prices are not crazy, compared to London, it’s true. What we should not do, though, is make the mistake of mixing that up with “cheap”. To buy a home on Coronation Street from a standing start, you’d still need a household income of around £36,000 and around £18,000 in the bank; the one in Bread, you’re looking at £40,000 and £20,000 as a minimum. And wages in the north are lower than those in the capital. While these options are not obviously unattainable like any of the London ones, they’re not obviously affordable either.

Several conclusions present themselves from all this. One is that it’s much harder to think of TV shows that you can narrow down to specific streets which aren’t set in London, although whether that’s a comment on British television or one on my brain I’m not sure. (Could go either way.) Another is that TV’s failure to get to grips with the housing crisis has rendered it ever less realistic. Why are there no bankers or hipsters on Albert Square? No annoying London refugees on Coronation Street, banging on about how the north is surprisingly nice?

Then there’s the fact that TV has not found a way of integrating the house price boom into its programmes, presumably because if you ever acknowledged that family homes in much of the country were now entirely unattainable to anyone who wasn’t in line for family money then whole swathes of British programming would be ruined and Kirstie Allsopp would be public enemy number one. The real effects of the housing crisis – cramped conditions and insecurity, people sharing with strangers well into adult life, the simple fact that today’s 30 somethings find it a lot harder to settle down and start families than their parents did – are so all consuming that if you started looking at them you’d find you could talk about little else. Perhaps this is why the soaps are dying, and the traditional family sitcom is dead.

My final conclusion from all this is that people who work in television seem to think that Chiswick, a genuinely plush west London suburb, is a lot more representative of lower middle class Britain than it actually is. I can’t help but wonder if this is because a lot of them live over there.

Incidentally, the reason I have just shamelessly ripped off my work from almost a decade ago is because I genuinely wonder if this might be my last chance to write this piece. Interest rates are finally going up; the economy is in line for a crunch. Perhaps, at long last, the crash is finally coming.

Then again, we’ve been saying that since 2008.

Map of the week

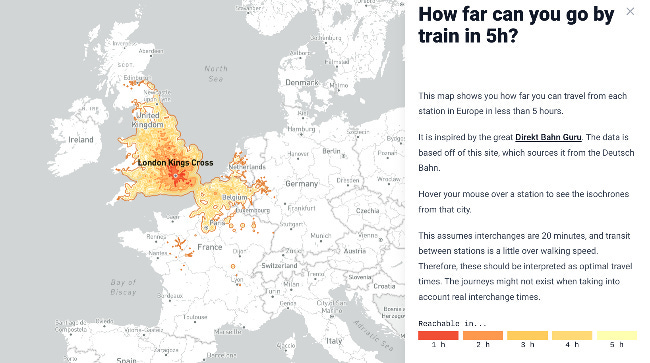

This week, some fabulous data visualisation, courtesy of a Parisian named Benjamin Td: an isochrone map, showing how far you can get in five hours from any point in Europe.

Note the blobs around places with high speed trains.

It might be slightly misleading – Benjamin has made the “assumption” that all the connections are 20 minutes, which, hmmm (“Since there is no guarantee that trains will connect perfectly, the map tends to be overly optimistic,” he admits). But it does highlight one of my favourite facts about this continent’s infrastructure: that, even decades after the Berlin Wall came down, it’s still a lot quicker to get around the west than the east.

I’ve had to keep screenshots to a minimum to ensure this newsletter doesn’t get too big for the email filters: this animation does a better job of selling the map to you than I’m going to be able to here. Or, even better, you could play with it yourself.

Self-promotion corner

That’s actually a lie, I can’t stand tea, but “a nice cup of coffee” felt like a cheat, even though coffee, from some perspectives, is a much better fit with philosophy and winning pointless, circular arguments alike.

Anyway! The article above is an extract from the archive of the Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything, a weekly newsletter which goes out every Wednesday at 4pm. If you enjoyed it, why not become a paying supporter? For a mere £4 a month or £40 a year, and every Wednesday afternoon you’ll get a bit on politics, some diverting links, an article on something from history/geography/language/whatever I’ve been obsessing about this week, and the map of the week. And for less than a pound a week, too! Click here to get started.

BUT: we’re all broke right now. If you can’t currently justify paying for some nerd’s substack (unemployed, underemployed, impoverished student, and so forth), just hit reply and I’ll give you a complimentary subscription, no questions asked. I am literally giving it away.

Or here are some things you can read now, for free:

“This is, of course, a catastrophically stupid idea.” My latest New Statesman bit, concerning (rapidly abandoned) plans to terminate HS2 five miles from Central London.

A lot of nonsense I’ve written about Doctor Who, which you can find here.