Stranger Than Fiction

This week: some thoughts on authorship and truth; and some notes on NATO naming conventions.

The woman I loved died, and less than ten months later A History of the World in 47 Borders hit the shelves, and I don’t wish to brag, but it went on to become a bestseller. The human brain, as I’d explored in an earlier book, is hardwired to go looking for patterns, to link cause and effect even when there are no links to be found. I would thus likely have somehow connected the two events – the karmic payback of one of the best things that has ever happened to me coming not long after the absolute worst – even if I had not spent the last day of Agnes’ life tidying up its final chapters before sending them to my editor.

All of which means it may have been a mistake to take Rebecca F. Kuang’s novel Yellowface on what was meant to be a relaxing holiday. The set up, if you’ve not had the pleasure, is that a failing – white – writer named June sees her more successful – Chinese – friend die suddenly, steals her manuscript and uses it to become a huge and unearned success. That conjunction between sudden tragedy and success – in an industry in which, for every good book that does well there are a thousand more that don’t, and all success depends on a hefty dose of luck – made it a deeply haunting read. I had to keep consciously reminding myself that our situations were not equivalent, that in my case there was not actually a connection between the two events, and also (this is an important detail) that I did actually write my book.

That is not, of course, the experience that the 1.5 million other readers will have had of Kuang’s book. They’re probably more interested in the stuff about racial politics in America, in publishing and on the internet, on which I am quite possibly the worst person to comment. June’s actions – profiting not just through a dead friend’s work, but through her identity, and being unable to truly grasp what she’s done – inspire an abhorrence that affects how people view both the protagonist and “her” book.

You can argue – I wouldn’t, but I don’t think it would be incoherent – that, in some ways, all this is rather strange. It’s nigh on six decades since Roland Barthes declared The Death of the Author, arguing that the meaning of a text lay not in authorial intent but in reader response. And the book published under June’s name is clearly meant to be A Great Book, so much so that I got the caps out. If that is the response people have to the text, why should silly questions like exactly who wrote it matter? We often know little about those who produced the art we enjoy. Does that make us unqualified to enjoy it?

But we do care – and both in the pages of Yellowface and the mind of the reader, what June has done is appalling. Who we think wrote something, and what their life was like, matters.

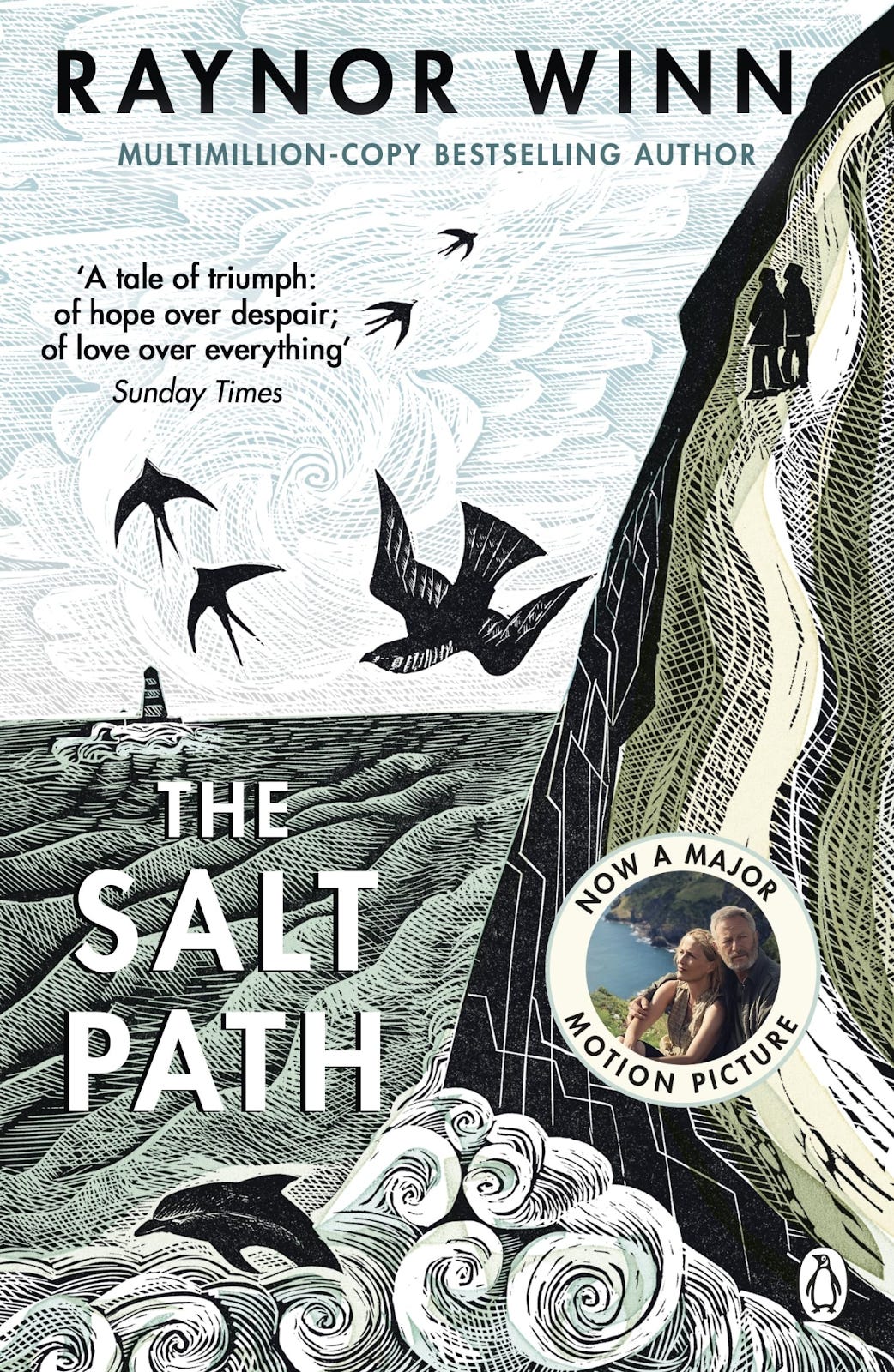

Witness the row following the revelations in last week’s Observer that Raynor Winn, author of the 2018 memoir The Salt Path, might not be all that she seems. The official story was that she and her husband lost their house due to a series of unfortunate events in which they had no hand, that he was diagnosed with a fatal illness, that they decided to walk the South West Coast Path warmed only by the kindness of strangers, and that this proved beneficial for his condition. No spoilers, but the Observer’s reporting casts doubt on almost all of that, and has done so just in time for the release of the inevitable mawkish film starring Gillian Anderson and Jason Isaacs. It’s all terrific fun, if you’ve been feeling deprived of updates from the Captain Tom saga of late.

As with June’s book-within-a-book, you can argue that none of this should matter. Vast numbers of people enjoyed the book and its sequels. The text that they enjoyed so much has not changed.

But if the Observer’s reporting is accurate – Winn has denied it, and claims to be taking legal advice – the context has. Perhaps the biggest threat to the book's heartwarming narrative lies in the awkward questions about Winn’s husband’s illness, the rare neurological condition corticobasal degeneration (CBD). Those told they have CBD rarely make it past eight years, and are visibly debilitated long before that. Eighteen years after his diagnosis, Moth Winn remains miraculously symptom-free.

That shadow of Moth’s illness is not incidental to the book’s success. There are lots of frank memoirs of illness and loss which don’t sell a million copies, and one reason for that may be – this observation shamelessly nicked from my pal Eddie Robson – because they lack the comforting subtext of “nature healed him”.

Undermine that subtext, and readers will feel betrayed. We care about the difference between fiction and non-fiction, and judge them by different rules. We care, too, that the people who produce our art are who they claim to be. You cannot simply swap a heartwarming underdog story about a couple going through unimaginable pain for an allegedly much less truthful work that is something else entirely, and expect the audience response to remain unchanged.

At any rate, this story is yet another reason that I remain unconvinced that AI-art is quite the threat some would have us believe. Because if either the resonance of Yellowface or the enthusiasm for The Salt Path story tell us anything, it’s that authorship is not incidental. Neither is truth.1

To end where we began, I understand rationally that, conjunction of timing aside, there is no connection between Agnes’ death and the success of 47 Borders. At the margin perhaps there’ll be people who bought it because they wanted to help and don’t know what else to do, just as there are those who subscribed to this newsletter for the same reason. (Thank you, by the way; she’d have been both delighted and furious.) Unlike the Winns, though, my personal experience of tragedy has nothing to do with the capricious publishing gods’ decision to smile on me. I was simply very unlucky, and then very lucky2, and in an essentially random universe sometimes those things happen together.

The real influence Agnes had on the book came through the conversations we had while I was writing it, and the support and encouragement she offered by being my partner. She didn’t do much for the book by dying; in life, though, she did plenty.

My new (old) book

Talking of books: this September my lovely publishers Wildfire are releasing a brand new and updated version of my acclaimed3 classic4 first book, The Compendium of (Not Quite) Everything. They’ve even put a gorgeous new cover on it, look:

I cannot, in all good faith, say it is worth your buying a copy if you already have one. Some entries have been updated; and there are half a dozen fresh ones, drawn from the pages of this very newsletter. But it is essentially the same book. Obviously I love it when people spend money on my stuff, but if you’re enough of an Elledge completist to want two different versions of the same book then a) awww, thank you, and b) get help.

However, it will make an excellent gift for the curious child or dad in your life, and if you haven’t read it already it would make an excellent addition to any bathroom so that visitors can flick through all human knowledge in bite-sized increments while on the toilet. Also, that cover is gorgeous. If you haven’t read it, why not give it a go?

Some notes on NATO naming conventions

In the second week of November 1983, Soviet security forces noticed some odd things happening on the far side of the Iron Curtain. The US and UK had begun to communicate in code at an unusually high rate. There were also unnerving periods of radio silence, and a rapid climb through the alert phases from DEFCON 5 (normal peacetime readiness) to DEFCON 1 (have you seen Threads??). Aware that new and scarier Pershing II missiles were due to be deployed across Europe any day now, Soviet Intelligence leapt to the obvious conclusion: the west was planning a nuclear first strike, and the east needed to get in first.

Obvious – but wrong. The Soviets had misinterpreted a simulation, Able Archer 83. NATO conducted the five-day war game every year, as a way of checking how the alliance would fare in a worst case scenario: this year’s exercise was just a bit more realistic than normal, and conducted at a moment when tensions were high. Luckily for all of us, a US general worked out why the Soviets had just readied their own nuclear forces in East Germany and Poland, chose not to respond, and the escalation didn’t go any further. The incident is generally ranked alongside the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1961 as one of the moments when the world came closest to nuclear conflagration.

But let’s not think about that: let’s talk instead about the oddly poetic label for the near-apocalyptic exercise.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.