What do you buy for the friend who has anything? Or the curious child in your life who you just want to keep quiet for a bit? Or, let’s be honest, your dad? (Dads are an important market.)

Unless you’re the sort of person who did all your Christmas shopping last spring as a way of whiling away the months in lockdown, you’re probably worrying about some variation of these questions right now. But fear not! For everyone in the world who isn’t me, annoyingly, there’s an answer: Why not buy them a copy of Jonn’s book?

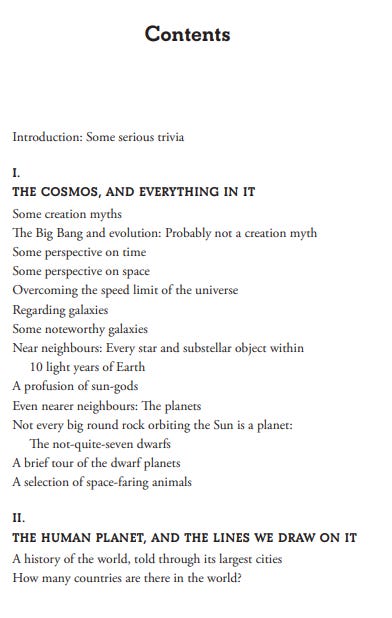

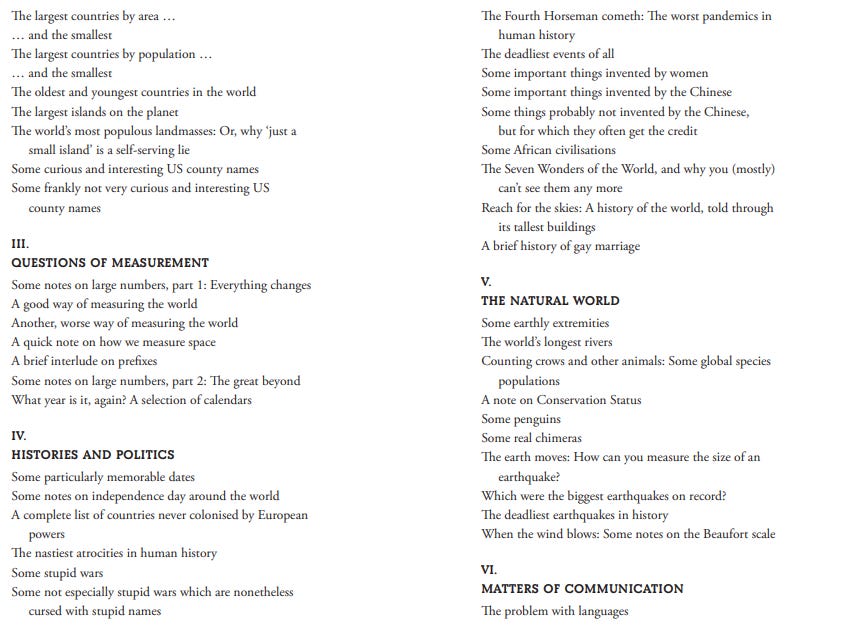

The Compendium of Not Quite Everything contains nearly 100 different entries, covering everything from some creation myths to some notes on real chimeras, to the important question of who brings presents at Christmas in different countries around the world. (I’ve included the book’s full contents list at the bottom of this email.)

So, here are three entries from the book. (You can find two more here.) These are copyrighted, so please do not re-post or share this extract elsewhere. But please do but the book for Waterstones, Amazon or Foyles. Go on. It’s Christmas.

The Big Bang and evolution: Probably not a creation myth

Here, best we can tell, is what actually happened.

In the beginning there was … something. Some physicists, on the grounds that the universe has been expanding, used to roll the tape back and assume that the universe must have begun as a singularity: an infinitely small, infinitely dense, infinitely hot point, containing everything. But other physicists doubt that theory on the grounds it results from general relativity, which applies at larger scales, and not the quantum mechanics that applies at tiny ones (the two theories have never got on). And, anyway, the information available to us only goes back so far. So the very earliest history of the universe is currently lost to us.

Then, around 10−36 seconds after the start of the universe, which is pretty soon, the universe suddenly began expanding, doubling in size, and doubling again, many dozens of times. This only lasted until sometime between 10−33 and 10−32 seconds after the singularity – it was over in a billionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second – but, once this ‘Inflationary Epoch’ was done, the scale of the universe had increased by many trillions of times. This is the ‘Bang’ part of the ‘Big Bang’, and explains, among other things, why matter and radiation are distributed so evenly around the universe. But at the time of writing no one seems to know why it happened.

As space expanded it began to cool, enabling the plasma of fundamental particles like quarks to coalesce into protons and neutrons. The universe was, by this time, perhaps a millionth of a second old. Within a few minutes it had cooled enough for some of those protons and neutrons to combine into what would later become the nuclei of helium or deuterium atoms. Actually creating those atoms took rather longer, however: recombination, the point at which the universe was cold enough for negatively charged electrons to begin orbiting positively charged nuclei, took around 370,000 years.

This, you may notice, is quite a jump in timescales.

The gradual cooling had another side effect. For the first time photons could travel freely through the universe without banging into electrons and scattering. That meant that space was now cold enough for light to pass through it: in other words, it had become transparent. This didn’t matter much, however: there weren’t any stars, so there was nothing to see even if there was anyone to see it, which there wasn’t. This bit’s known as the ‘Cosmic Dark Age’.1

After a couple of hundred million years, gravity caused clumps of gas to collapse in upon themselves and ignite, and the resulting stars to gather together in groups we’d later call galaxies. These first stars were probably bigger – hundreds, even thousands of times bigger – and shorter-lived than today’s. They also fused hydrogen and helium atoms together into heavier elements, which scattered around the universe when they went supernova. This would prove very helpful for anyone who happened to live in the universe later.

Around 4.5 billion years ago, a mere 9.3 billion years after the universe began, a particular cloud of gas on one of the spiral arms of the Milky Way collapsed to form another star. The leftover matter around it coalesced to form moons and planets, including one orbiting its sun at a distance of roughly 93 million miles. At some point – possibly quite soon afterwards, possibly it took as much as another billion years – life began on this planet, probably around the hydrothermal vents: points on the bottom of the ocean floor, at which water, superheated by volcanic magma, explodes back into the open sea.

Some of these single-celled life forms did better at surviving than others. Occasionally, a random mutation would give particular strains an advantage, and they would reproduce while others died out. Over the aeons that followed, some evolved to breathe oxygen, or to combine with others to form multicellular organisms. Some became plants; others animals; some developed more complex brains and nervous systems thanks to their clever use of a backbone. Until, after a lengthy period in which the planet was dominated by the giant reptiles we call dinosaurs, smaller, furrier ones known as mammals began to take over.

And then, around 4 million years ago, a group of apes who walked upright instead of on all fours decided to make their homes on the savannah instead of in the forest. They learned to build shelters and make tools, to communicate with speech, to hunt and farm and trade. A few thousand years ago they began writing things down, so their descendants could read about them. A few hundred years ago, they learned how to make books, and a couple of decades back they invented the internet, so that anyone with an electronic device could access pretty much all the world’s knowledge from just about anywhere on the planet.

And it turned out that most of these apes didn’t really care about all the world’s knowledge. They just wanted to be rude to strangers and to look at pictures of other, smaller, furrier mammals.

And that brings us pretty much up to date.

Some stupid wars

One could argue that, on a fundamental level, all wars are pretty stupid. Indeed, one could make a compelling case that the First World War – one of the most destructive wars in history, fought for what appears, to modern eyes, to be No Reason At All – is the stupidest of all.

But quite enough of this book – indeed, of reality – is forcing you to come to terms with the futility of human existence already. So, for this list at least, let’s restrict ourselves here to some war stories that are really stupid.

THE WAR OF THE LEAGUE OF CAMBRAI (Europe vs itself, 1508–16)

From 1508 to 1510, the Pope allied with France to curb the power of Venice. From 1510 to 1512, the Pope allied with Venice to curb the power of France.

After successfully driving the French out of Italy, Venice and the Pope fell out. And so, Venice allied with the French against the Pope.

In 1516, after tens of thousands of deaths, the various powers signed a treaty that returned the map of Italy to a state remarkably similar to the one it had occupied in 1508. Eight years well spent.

THE WAR OF THE COW (Prince-Bishopric of Liège vs the Marquisate of Namur, 1272–8)

A peasant in what is now Belgium steals a cow during a jousting tournament. Said peasant is offered the choice between returning the cow or being executed. Peasant, not unnaturally, opts to return the cow, but is executed anyway. The peasant’s lord demands recompense, gathers a posse and destroys a castle. Rival lords respond by setting fire to some things. This keeps going for quite some time until 60 villages are destroyed and an estimated 15,000 people are dead.

Because somebody stole a cow.

THE ANGLO ZANZIBAR WAR (Britain vs the Zanzibar Sultanate, 27 August 1896 – 9.02 a.m. to 9.40 a.m.)

When the pro-British Sultan of Zanzibar died, suddenly and quite possibly suspiciously, he was succeeded by the rather less pro-British Sultan Khalid bin Barghash. The British Empire treated the fact that the newcomer hadn’t asked it for permission before becoming sultan, as specified in a treaty, as casus belli, and sent an ultimatum demanding Khalid stand down and leave the palace by 9 a.m. Khalid declined, and barricaded himself in.

There followed precisely 38 minutes of bombing, during which around 500 Zanzibar troops were injured or killed, three Zanzibar boats were sunk, and one British sailor was very slightly wounded. Khalid claimed asylum in German East Africa, Zanzibar was swallowed by the British Empire, and then – a nice touch, this – the British military sent their enemies a bill for the cost of the shells they’d fired at them. It had been the shortest war on record.

THE AMERICAN INVASION OF ENGLAND (US vs Britain, 23 April 1778)

John Paul Jones was a Scottish-born sailor remembered by history as a father of the US Navy. His responsibility for the only US invasion of British soil, however, is something he’d probably rather history forgot.

In the spring of 1778, his ship, the USS Ranger, was hanging around in the Irish Sea annoying British shipping when Jones had an idea: invade the port of Whitehaven, on the northwest coast of England, where he had begun his career, spike the cannons and set fire to the hundreds of ships in the harbour.

Unfortunately, his best officers weren’t keen on the plan. Several of those who were keen on the plan landed in the wrong place, entered a tavern seeking material to help start a fire, and only emerged, several hours later, rather the worse for wear. At that point, one of them ran off to sound the alarm, so that the town knew what was happening. More embarrassingly for Jones, they knew who was behind it. The one small fire his crew managed to set was easily extinguished. The US never invaded Great Britain again. (*Correct as of time of writing.)

THE GREAT EMU WAR (Australia vs some large birds, 1932)

Very possibly the most ridiculous war in human history. It’s not just that the Australian army went to war against some emus. It’s that the emus won. #

In 1932, the settler farmers of Western Australia were growing increasingly annoyed that large flightless birds were running amok and ruining their crops. So, to help out, the Australian government sent in the army, armed with machine guns.

You’d think that’d make for a rather one-sided conflict. It didn’t. It soon turned out that emus could run faster than the trucks on which the guns were mounted could move. This didn’t matter as much as you’d think, however, because the guns could only be fired when the trucks weren’t moving anyway. The emus also employed other cunning military tactics such as ‘zig-zagging’.

By the fourth day of the campaign, army observers were reportedly concerned that each pack now had its own leader. “If we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds, it would face any army in the world,” said Major G. P. W. Meredith, who commanded the human forces. “They can face machine guns with the invulnerability of tanks. They are like Zulus whom even dum-dum bullets could not stop.”

The army withdrew. But the farmers kept kvetching, so a few days later they tried again. This means that there were, from some perspectives, two emu wars.

Both had the same result. The emus sustained higher casualties – but they did not cede an inch of ground. In any other military conflict, that would be recorded as an emu victory

Last words down the ages

Let’s be honest with ourselves: at least some of these, especially the earlier ones, are apocryphal, if not totally made up. But they are all commonly attributed, by literary or other sources.

Archimedes, c.212 BCE – “Don’t disturb my circles!”

The Greek mathematician was speaking to the soldier who interrupted his work during the Roman capture of Syracuse. The soldier responded by killing him.

Augustus, 14 CE – “The drama’s over: applaud.”

The first Roman emperor. His other commonly cited last words – “I found a Rome of bricks, and leave one of marble”, or similar – were actually his last words spoken in public.

Jesus, 30 CE – “It is finished.”

Not as profound as it sounds – the words, reproduced in the Gospel of John, refer to a drink, not this mortal coil. There’s also a debate to be had over whether these actually count as last words, what with the whole resurrection thing to contend with, but that’s for another day.

Nostradamus, 1566 – “You will not find me alive at sunrise.”

French seer, getting a prediction right for once.

Lope de Vega, 1635 – “All right then, I’ll say it. Dante makes me sick.”

Spanish playwright. We’ve all thought it.

Dominique Bouhours, 1702 – “I am about to – or am going to – die. Either expression is acceptable.”

French grammarian, on it till the end.

Adam Smith, 1790 – “I believe we shall adjourn this meeting to another place.”

The father of capitalism, showing that economists can be poetic after all.

Marie Antoinette, 1793 – “Pardon me, sir, I didn’t do it on purpose.”

The Queen of France accidentally steps on her executioner’s foot.

Jane Austen, 1817 – “I want nothing but death.”

Asked by her sister Cassandra if she wanted anything. Unexpectedly metal for Jane Austen.

Sam Patch, 1829 – “Napoleon was a great man and a great general. He conquered armies and he conquered nations. But he couldn’t jump the Genesee Falls. Wellington was a great man and a great soldier. He conquered armies and he conquered Napoleon, but he couldn’t jump the Genesee Falls. That was left for me to do, and I can do it and will!”

American daredevil, who proceeded to jump to his death. So successfully had Patch managed such stunts in the past that a rumour briefly circulated that his ‘death’ was a stunt in itself, and that he was in hiding, enjoying the attention. But the following spring, his body was found in the ice, which rather put paid to that theory.

John Sedgwick, 1864 – “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance!”

Unionist general fighting in the US Civil War, speaking shortly before discovering he was wrong. So perfect was this piece of comic timing that the line has been reused in at least one sitcom.

Aubrey Beardsley, 1898 – “I am imploring you – burn all the indecent poems and drawings.”

Who among us has not at some point had the same thought as the English illustrator?

James Joyce, 1941 – “Does nobody understand?”

Irish novelist, inadvertently anticipating the next few decades of responses to his later work.

Joseph Stalin, 1953 – “I don’t even trust myself.”

A rare moment of insight from the Soviet leader.

Nancy Astor, 1964 – “Am I dying, or is this my birthday?”

The American-born viscountess had just awoken to find herself surrounded by her entire family.

Harold Holt, 1967 – “I know this beach like the back of my hand.”

The Australian prime minister, shortly prior to taking a swim, after which he was never seen again.

Thomas J. Grasso, 1995 – “I did not get my SpaghettiOs. I got spaghetti. I want the press to know this.”

A double murderer focuses on the real issues before his execution by the state of Oklahoma.

The contents pages

So what else is in the book? Well I’m very glad you asked.

Why not order the book from Waterstones, Amazon or Foyles?

(Please do not write in to tell me why not.)

Also, if you enjoyed that and you want more of this kind of stuff, why not subscribe to the full, weekly Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything service? Then, for less than £1 a week, you’ll get an email every Wednesday.

The term ‘Dark Ages’ generally refers to the centuries from roughly the fifth to sometime between the tenth and fifteenth: the period after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, but before the Renaissance. Historians dislike this term because of both its negative connotations and its Eurocentrism. It ignores the fact that, on much of the planet – in the Islamic world, in China, even in southeastern Europe – civilisation was chugging away, and chucking out scientific advances as fast as it ever had. I would, however, suggest another reason to dislike it: it looks stupid compared to the literal Dark Age, which went on for quite a lot longer.