This one went to paying subscribers back in May. As ever, if you want stuff as I write it, rather than a tiny fraction of it some random time later, you should…

The thing about living in any big city is that you never do the stuff the tourists come to see. That, at least, is my excuse for why it is that, until recently, I’d never actually visited Highgate Cemetery, probably London’s finest and most famous necropolis. I did try to, once, on one of my walks – but I hadn’t realised you had to pay to go in, and I was in a bit of a huff about that and also running late. And so I just didn’t bother. And then, suddenly, 10 years had gone by.

I don’t regret that, though, because it meant that a few weeks ago I got the experience of visiting for the first time. It is gorgeous, genuinely one of the prettiest and most peaceful open spaces I’ve ever seen in London. Really, it’d be a privilege to be dead there. (Literally: a plot will set you back upwards of £20,000.)

So if you do fancy a sunny day out among the dead, what should you expect? Well, firstly, you do, as noted, have to pay to go in – £10 for an adult at a little booth on Swain’s Lane, just by the entrance to the cemetery’s east side. That fine thoroughfare splits the cemetery in two, and the nice lady in the ticket booth advised us to begin on the more fashionable1 west side.

And so, we crossed the road and passed through a chapel, to find a courtyard surrounded by colonnades and paths leading upwards. Dotted around the place were signs asking visitors to behave respectfully as there was a funeral today. This to me raises questions about what exactly sightseers have got up to here in the past.

Starting on the west side turned out to be good advice: it slopes steeply up the side of Highgate Hill, climbing what feels like several storeys, so you probably don’t want to be doing that at the end of your visit. We wandered aimlessly round for some time, keeping as suggested to the firmer, safer paths, reading random graves, generally enjoying being in a quiet shady place on a sunny day. Eventually, it occurred to one of us that perhaps we should look at the map, if only to see if we could spot anyone we recognised.

It was only then that I realised we’d already passed two famous graves without noticing. One was that of Alexander Litvinenko, the Russian dissident poisoned by the Putin government back in 2006. The other, just a few feet from where we stood, was that of one Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou, who was laid to rest on one side of Lesley Angold Panayiotou, with Melanie Panayiotou on her other. There was a sign reminding people this was a real grave, and asking them not to photograph it; there was also a man, kneeling, sombrely, and photographing it.

This was of course the grave of George Michael, who died on Christmas Day 2016, and was a genuinely great man. I felt quite emotional.

From there we continued climbing, through another colonnade – great spot for some disrespectful snogging, should you happen to be a teenage goth – up the fabulously named Egyptian Avenue to the Circle of Lebanon. There stand a series of catacombs, grand walk-in tombs, some set aside for entire families. I have no idea, if I’m honest, why anyone would do such a thing in this day and age, or any day and age that’s come about in the past few centuries; but they were beautiful and peaceful and quite the best looking tombs I’ve come across anywhere in England. Look:

As we climbed back down the slightly uneven Faraday Path – actually not then; we’d have fallen over; that would have been a ridiculous idea, but I need a segue – I looked at the guide the nice lady in the booth had given in an attempt to learn some things.

Firstly, cemeteries like Highgate grew out of what is delightfully described as “the burial crisis”: the moment in the early 19th century at which, thanks to a combination of urbanisation and population growth, the churchyards which had traditionally played host to the dead started running out of space. Outbreaks of cholera and typhoid, apparently, “made action more urgent”. Oh dear.

Thankfully, capitalism came to the rescue/saw an opportunity to literally make money from death [delete to taste]. Inspired by Père Lachaise in Paris, companies started setting up private cemeteries done up like gardens on what were then the fringes of London. Highgate, established by the London Cemetery Corporation in 1839, was the third of what were later named the “magnificent seven”; the less picturesque east side extension followed 21 years later.

The need for the extension highlights a problem with this business model. Graves were sold in perpetuity: after a while the space simply ran out, and the cemetery became unprofitable. Worse, as those who’d been left behind too passed on, graves increasingly went untended. The London Cemetery Company was declared bankrupt in 1960; where other cemeteries were taken over by councils and run as taxpayer-funded parks, Highgate is now run by a charity.

A number of other highlights leapt out at me as I read the guide. The very first listing on the notable graves pages is John Atcheler (1792-1867), “Horse slaughterer to Queen Victoria”, which is the best job description I’ve encountered in some time. I learned too of the third Lord Cheylesmore, one of three in the family mausoleum, and the first British peer to die in a car crash. Or consider Baroness De Munck (1768-1841), the pelican on whose grave marks the sacrifices she made in order for her daughter to become a famous opera singer (alright, mum, bit much). Or Sir Benjamin Hawes (1797-1862), who “had the unenviable reputation of obstructing Florence Nightingale at every opportunity”. Or social affairs journalist Dawn Foster, who died suddenly in 2021, whose friends raised the money for her grave, and who is, I think, the only occupant I knew personally. All these are interred at Highgate, along with roughly 170,000 others in 53,000 graves.

We didn’t have time for those, though, as we had someone to see back across the road:

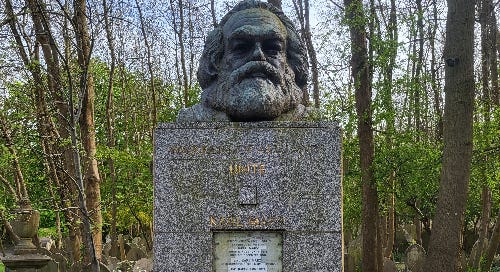

Karl Marx’s tomb is by some distance both the most famous and the most impressive tomb in the place, which is perhaps surprising since he was famously not a big earner and relied heavily on the financial support of his friend Friedrich Engels. There is, it turns out, a reason for this: this is actually his second tomb. His first had been rather less impressive, but was replaced by this fine resting place in 1956 thanks to funding from the Communist Party of Great Britain. Wasn’t that nice of them?

Getting a decent look at Karl proved surprisingly hard – a couple whose accents I couldn’t place were already looking and seemed to slightly resent our presence. So after a while we wandered on.

The west side of the cemetery has a different vibe to the eastern one. It’s flatter, less wooded and less dramatic; Marx aside, you could be in any pleasant suburban cemetery, and we were running out of time before it closed. So we didn’t linger long, even if I nearly got us locked in by being slightly too slow in the toilet. I also, alas, missed the chance to buy a Karl Marx plushie in the gift shop.

After leaving, and rifling through the programme properly, that wasn’t all I’d missed. George Eliot! Michael Faraday! Trigger from Only Fools & Horses!2 The founder of Crufts!3 Worst of all, I missed another actual hero of mine, Douglas Adams, of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy fame. I could have seen Douglas Adams grave, and I was too distracted by the ambience to properly look at the programme and know! I’ll have to go back.

But it was, nonetheless, a rather lovely afternoon, my only complaint about which was that it’s slightly too long a walk to a half- decent pub afterwards. If you find yourself with a few hours to spare in north London I’d genuinely recommend it. And if you have any other suggestions for tourist spots in London I might somehow have missed, and which I can use this newsletter as an excuse to visit, give me a shout.

A reminder, in the unlikely event that you need one, that my latest book, A History of the World in 47 Borders: The Stories Behind the Lines On Our Maps, is available now. I very much enjoyed seeing someone at Heathrow Airport seriously consider buying it and then not doing that.

Also, while we’re here, perhaps you should:

And more expensive! £40,000.

Roger Lloyd Pack.

Charles Cruft.