The David Tennant of US presidents, and also some other guy

On the Grover Cleveland / Benjamin Harrison / Grover Cleveland era, 1885-1897.

This originally went out to paying customers back in October, at a point when we still had hope that a) Donald Trump would lose the popular vote, as well as b) not become president again, and so c) we would never have to to think about tariffs again. Oh god.

Anyway:

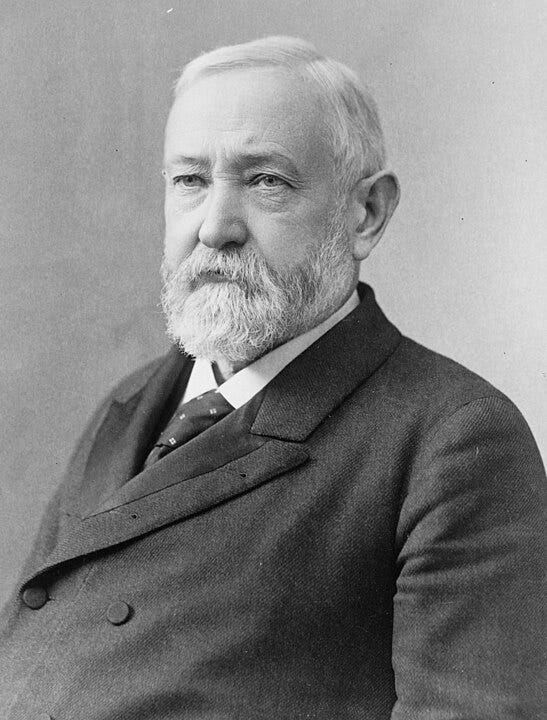

Half-forgotten US president of the week: Benjamin Harrison

Lived: 1833-1901

23rd president: 1889-1893

When I started this series, the plan was that entries would be brief – the same 300-400 words I’d give to an amusing map of Birmingham, upside down, or a particularly weird species of wombat. But the issue I ran into was that I kept discovering things that were too interesting to leave out. Okay, finding the fascinating in the potentially tedious is very much my MO, and I love a bit of US history, which is why I was doing it in the first place. But nonetheless, this was not the plan.

I am delighted, then, to be able to tell you: I’ve finally found a president whose story is so completely and utterly tedious I may actually need to pad it out. Buckle up.

There are two things to know about Benjamin Harrison up front. One is that he was from a big Virginia political dynasty. His great-grandfather, Benjamin “the Signer” Harrison, had signed the Declaration of Independence; his grandfather, William Henry, had actually become president, briefly.1 (No coat, dead in 30 days; we don’t need to go over that again.)

The other thing to know about Benjamin Harrison that he was only 5’6. As a result, according to his official White House biography, “Democrats called him ‘Little Ben’; Republicans replied that he was big enough to wear the hat of his grandfather, ‘Old Tippecanoe’.” I’m not sure this is a clapback that’s really stood the test of time.

Like seemingly everyone in 19th century US politics, Harrison was born and raised in Ohio, where he trained as a lawyer. After fighting in the Civil War, he failed to be elected governor of Indiana at the 1876 election, when the Democrats tarred him with the damning label of “Kid Gloves Harrison”, and became a senator instead. The source of that nickname may have been that – this from the White House bio again – “he championed Indians”. If so, that would later come to seem pretty ironic.

Despite these struggles, Harrison became the Republican party’s candidate for president on the eighth ballot at the contested 1888 convention. His opponent in the general election that year would be the Democrat incumbent, Grover Cleveland.2

I’m going to dwell on Cleveland for a moment, partly since he’s pretty essential to the story of US politics in this era, partly to fill out my word count, but mostly because he’s a damn sight more interesting than Boring Gloves Harrison.

Less forgotten US president of the week: Grover Cleveland

Lived: 1837-1908

22nd president: 1881-1885; 24th president: 1889-1893

Stephen Grover Cleveland was a lawyer (aren’t they all) but didn’t come from Ohio (upstate New York). He began his political career when elected mayor of Buffalo in 1881, and made it to the governor’s mansion the following year. There his opposition to tariffs, subsidies and imperialism propelled him first to national attention, then to the White House. He had been in politics just three years.

In Washington, Cleveland stuck to the principles that had got him there in the first place: he seems to have hated special interests, and argued that handing out money to such malingers as drought-stricken farmers or the disabled would “weaken the sturdiness of our national character”, which is lovely. He was also, incidentally, the only president ever to marry in office: he arrived in Washington a bachelor, despite being nearly 48, but married 21 year old Frances Folsom in the second summer of his presidency. Absolute legend. In no way problematic.

The key things to bear in mind about Cleveland are that he was a) an absolutely doctrinaire conservative, b) extremely popular and c) a Democrat. In fact, he was the first Democrat elected since the Civil War, which had rather wrecked the party’s reputation. The only other Democrat to reach the White House before the Great Depression and Franklin Roosevelt changed everything would be Woodrow Wilson, a man famous for two things: creating the doomed League of Nations after World War I, and being a massive f*cking racist. It’s all a reminder that the party system in this period is entirely, from a modern perspective, upside down.

So: this was the guy in the White House when Benjamin Harrison ran for president in 1888. The challenger campaigned using a “front-porch campaign” which basically meant he stayed at home and let delegations come to Indianapolis, where he made speeches at them. This went badly, in so far as he received 100,000 fewer votes than the popular Cleveland; it went incredibly well, in that he absolutely smashed the electoral college, winning 233 votes to just 168. He managed this, the White House claims, because “although Harrison had made no political bargains, his supporters had given innumerable pledges upon his behalf”. This is a delightful euphemism: one Pennsylvania party boss said that Harrison would never know “how close a number of men were compelled to approach… the penitentiary to make him President”.

At any rate, Harrison was the second president to be directly descended from a predecessor. Over the next four years, he tried but failed to annex Hawaii; signed the first anti-trust laws to regulate monopolies; and oversaw the first billion-dollar congressional budget in peacetime. Probably the most noteworthy thing to happen during his presidency, though, was the rise of the Ghost Dance spiritual movement among the Lakota, which resulted in the horrific massacre by US troops at Wounded Knee, and the president’s push for assimilation. So much for “kid gloves.”

The White House bio, oddly, doesn’t mention this. Instead it dedicates two whole paragraphs to “the most perplexing domestic problem Harrison faced... the tariff issue”, which is a measure of quite how thrilling his presidency really was. The high tariff rates apparently meant there was a surplus of money in the Treasury, which was in some way bad for business. Fixing this involved the words “reciprocity provisions”. The details here might be fascinating, but sadly I will never know for sure because I have to do literally anything else.

(Just for the record: re-reading this piece, to send it to you fine people today, it was at roughly this point when much of this started feeling ever so slightly familiar. History doesn’t repeat, but it does on occasion rhyme.)

Anyway, the surplus evaporated, the economy turned, and the Republicans got whopped in the 1890 midterms. Two years later, Grover Cleveland won the popular vote for a third time and the electoral college for the second, and Harrison became the meat in a Cleveland sandwich. This means that Donald Trump is in some ways very like Grover Cleveland (a conservative, who serves two non-consecutive terms as president) while also being almost entirely unlike him (utterly lacking in principles, and only won the popular vote on the third attempt).

Cleveland served another four year term, in which his main achievements were being shitty to striking railroad workers (“If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postcard in Chicago, that card will be delivered”) and making a principled but deeply unpopular stand against using the might of the federal government to fight an economic depression. Consequently, his party deserted him: he did not get to fight a fourth election.

As to Harrison: he went home to Indianapolis, married a widow and died, in 1901, as he had lived: boringly.

Although if you can’t afford it right now and still want to read, just hit reply and ask for a comp. You can have one. Really. I’m writing it anyway, so.

The Signer was actually Benjamin Harrison V, while his eldest son, William Henry’s older brother, was known as Benjamin Harrison VI. Disappointingly, they seem to have abandoned the numbering by our Ben.

One of the other candidates that year, incidentally, though not a very likely one, was the former slave and civil rights campaigner Frederick Douglass. The first black man ever to be proposed at a major party nominating convention, he received a single vote from Kentucky on the fourth ballot.