The fifteen colour problem

Also: the trouble with England.

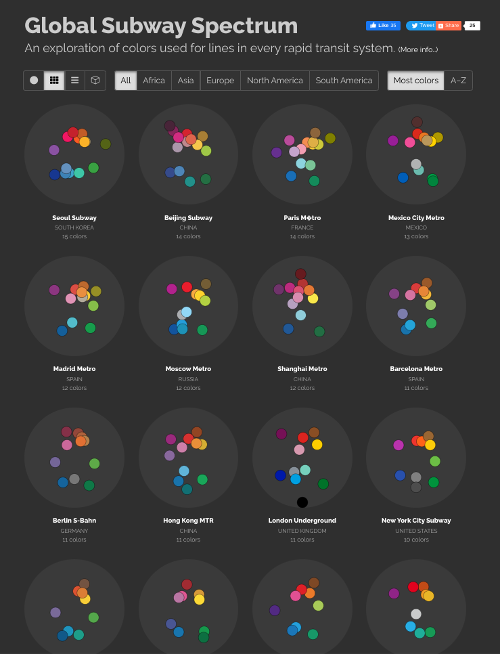

A few years ago, a Chicago-based designer named Nick Rougeux published the “Global Subway Spectrum: An exploration of colours used for lines in every rapid transit system”. It allowed you to see every colour then used by every metro map in the world on a single wheel:

Or as a grid:

You could see the colours used by individual cities, too:

It’s a lovely project, from which I learned a variety of interesting things. It highlights, for example, that there are a lot more metros in Europe and Asia than the Americas or Africa, which I already knew but which it was useful to quantify. It also shows that not all colours are equally popular, so that while the metro maps of the world are covered in lines of red, blue and green, there are slightly fewer yellows and purples, even fewer pinks, browns and oranges, and hardly any greys at all. Only two cities in the world had lines coloured black: Bilbao, and London. This perhaps explains why the Northern Line is so cursed.

Perhaps the most important thing it highlights, though, is that there’s a limit on the number of colours a map can comfortably contain. The average human eye can be expected to distinguish between, say, light blue and dark blue, or violet and magenta; but include more than a couple of a similar shade, and they stop being something you can identify by sight. The result seems to be a hard cap on the number of colours a map can use and still be read at a glance. At the time Rogeux did his work, at least, only 12 networks used more than 10 colours, and only Seoul used as many as 15. That was a few years ago, of course, so things may have changed. But I doubt that they have changed much.

London currently uses 11 colours for its Tube lines, plus another four (DLR, Overground, Elizabeth and Trams) for services shown in the same style on its Tube & Rail Map. We learned a few weeks ago, though, that money has been set aside to split the Overground into a number of individual lines, each with their own identity – and thus, one suspects, their own visual branding. I personally think that should mean replacing one colour with seven, realistically the most likely number at present is six.1

That will mean five additional colours – which, if you’re counting, would bring us to 20. It seems extremely unlikely that a map containing 20 colours will still be legible at a glance: after all, it’s already been forced into using four different shades of green. So what is to be done?

Looking around the world, there seem to be a number of different options. The New York Subway has a couple of dozen routes, but bundles them together, so uses perhaps half that many colours: that means that, when navigating the system, you can’t just rely on colour, but need to pay attention to the “bullet”, the number or letter in a coloured circle representing the route, too.

Paris uses multiple quite close shades – look at the number of yellows, or pale greens – but uses several tricks to prevent confusion. One is using thicker lines for the RER, a sort of more venerable equivalent of the Elizabeth line (although often serving geographic areas more on a par with, say, the Central line); this, oddly, was missed by Rougeux’s analysis. Another is simply keeping similar colours apart where possible – the pale greens used for lines 6 and 7bis2 are pretty similar, but they don’t interchange.

London relies a little on the New York trick already: the District, Northern, Metropolitan and Lea Valley bit of the Overground could all be argued to be multiple lines bundled up together into a single colour (though I for one am not happy about it). It arguably uses elements of the Parisian one too, keeping the green of the Trams a long way from other greens of DLR and Waterloo & City (though it does touch the District at Wimbledon, and also all the green lines except the Trams get tangled in the City, so perhaps it doesn’t do that at all).

But London’s cartographers have generally relied on a trick of their own: using totally different types of graphics to show different types of line. Once upon a time, that meant showing national rail routes as white with a narrow black boundary, to suggest they’re not as important as proper tubes. It’s also used thicker, coloured version of these “hollow tram lines”, to show the East London Line (in Metropolitan mauve) until 1990, and to show non-tube bits of the network today. Meanwhile, today’s Tube Map shows Thameslink, and today’s Tube & Rail Map shows National Rail services, in different styles of hatching, their colours interrupted by white patches.

I suspect we’re going to see more of that now: instead of all Overground lines being orange tramlines, they’ll be shown as a variety of colours for different lines. This’ll work, I suppose.

But I’d argue there’s a case for thinking more like Paris, though – using different colour palettes and line thicknesses to suggest a hierarchy of different services. Bright colours could be restricted to frequent services like the Tube; pastel colours or narrower lines used for other services. That’s exactly what my favourite amateur take on London’s rail map does: the one by Jug Cerovic, which I covered in September 2021.

All this would require a complete rethink of the tube map, in a way TfL has shown no interest in doing, of course. But given how ugly this once beautiful thing has become, as it’s been loaded up with more services and more information (fare zones, accessibility and so on), many people – by which of course I mean me – have been arguing for something of this sort for years. The map will need to be rethought anyway, if the Overground network is given individual line identities. Perhaps, at last, this is the time.

Map of the week: The “trouble with England” edition

The above, you will notice, is not a map. It is, however, one of my favourite xkcd cartoons, and it’s occasionally haunted me when I’ve been sat on the internet, arguing, as you do, about local government boundary reform. Sure, some kind of spiritual successor to the 1969 Redcliffe-Maud report could, in theory, force us to rethink the administrative geography of this country, to bring councils, NHS bodies, Local Enterprise Partnerships and so forth under a single, more rational set of boundaries... but Redcliffe-Maud was never implemented because of fierce local opposition. Would a successor really do any better? Would stuff get chipped away? Is there a danger that here, too, an attempt to create a single set of boundaries could instead merely add yet another set to the list?

Well, very possibly, but I am shaking off my doubts and suggesting we should do it anyway, because look at this gif, headed “England’s incoherent policy geographies”. It shows 13 different competing ways of dividing England up for governance. The replies to this tweet suggested a number of others that had been missed.

The gif is built on the findings of a report by the Institute of Government and the Bennett Institute of Public Policy at Cambridge. It argues that England’s internal administrative geography is unusually messy, compared to peer nations – in part the legacy, as that cartoon would suggest, of previous attempts to establish devolved institutions. This is a problem: partly because it makes it harder to coordinate different policy areas, partly because it makes it damn near impossible to know who’s accountable for actually bloody fixing anything. Council officials, the report notes, are often blamed for failures in areas over which they have no power whatsoever – areas, indeed, in which even they may not be quite sure who to complain to.

By contrast, areas like Greater London and Greater Manchester, where the administrative geography is more aligned, have an advantage: it’s clear what levers to pull and who to blame when they don’t work. All this makes a pretty compelling case, the report argues, “for considering whether England would benefit from having more ‘general purpose geographies’ as opposed to its multitude of task-specific agencies operating with an array of different, overlapping borders” – in other words, for a big bang reform like Redcliffe-Maud, and folding these various other institutions in.

Or to put it another way, I Was Right All Along. Which is always pleasing. You can read the full report, with its many maps, here.

Please subscribe, this puppy is hungry

The articles above is an extract from the archive of the Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything, a weekly newsletter which goes out every Wednesday at 4pm. This week’s edition included some notes on the concept of “dark ages”, and asked: why do right-wing papers hate their readers?

Given all that, why not bite the bullet and become a paying subscriber? Every Wednesday afternoon, you’ll get a bit on politics, some diverting links, an article on something from history/geography/language/whatever I’ve been obsessing about this week, and the map of the week; and get a warm glow of satisfaction that you’re helping me do fun and nerdy things not nasty corporate ones. And all for just £4 a month or £40 £28 a year! Can’t say fairer than that now can I, Rodney.

BUT: we’re all broke right now. If you can’t currently justify paying for some nerd’s substack (unemployed, underemployed, impoverished student, and so forth), just hit reply and I’ll give you a complimentary subscription, no questions asked. I am literally giving it away.

Alternatively, if you don’t want to do any of that, but would like to hear me occasionally talking about the news and how the media covers it, then why not subscribe to the hit new podcast Paper Cuts, in which journalists, comedians and the occasional historian discuss the news. You can hear us here.

I don’t imagine anyone is listening to my argument that the stopping pattern makes the Chingford line different from the Enfield/Cheshunt one; it’s not that much more complex than the Metropolitan Line, to be fair.

“Bis” is the French equivalent of the “a” that follows a number. Where an extra house in Britain besides number 3 might be called “3a”, in France it’d be “3bis”. The Paris Métro has two small lines using this terminology, 3bis and 7bis, each split from their numbersake to simplify service patterns. The local transport authorities have considered connecting them into a new line, via an existing tunnel and the disused station Haxo, but it hasn’t reached the top of the priority list as yet.