The Gordian Knot

This week: why is the British state broken? Also: fraudsters hate this one weird trick for spotting man-made numbers! And a map of what’s left of the Roman limes.

When a computer stops responding to your instructions, you start mashing the buttons instead. For the last few years, the British electorate has repeatedly voted for change – yet change has consistently failed to come. Little wonder a fair chunk of them now seem ready to kick everything over in frustration.

When I used that metaphor before, it was in a quick think piece about the effects of government stasis, not an in-depth investigation into what had caused it in the first place. For that, you need to turn Power Failure: a deeply researched report written by Phil Tinline and published by the Future Governance Forum. Here’s the opening line:

To restore voters’ trust in mainstream liberal democracy, Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s administration has to deliver the change it promised in opposition. To do that, the government needs a new approach to power.

That approach can be summed up as “use it”.

The report identifies a couple of ways in which the British government has disempowered itself. One is the way an ostensibly neutral reliance on fixed rules and objective numbers instead of political judgement has worked to bolster the status quo. The big one, though, is it’s no longer clear where power actually is. Over half a century or more, it’s been pulled out of local government and other autonomous institutions to the centre, only to be dispersed again to agencies, quangos, outsourcing firms – partly because of ideological motives concerning private sector efficiency, partly due to political ones about reducing the chance a minister would have to take the blame. The result is that, today, “responsibility sits in so many places, it sits nowhere”.

Tinline goes on to explore several different examples to illustrate all this: the power of corporations; the rise of privatised utilities and outsourcing firms; the role of judicial review. Perhaps the most interesting, though, is the one about the state’s financial muscle. Crises like the 1976 International Monetary Fund (IMF) crisis and Black Wednesday in 1992 led to a consensus that politicians simply couldn’t be trusted to manage the public finances, even though this was to a large extent the job. The result was an increase in the power of the Treasury, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) at the hands of the people the public had actually voted in.

How to fix this, and return power to the democratically elected government? The report’s recommendations to ministers include reminding the Bank where its authority comes from, making clear to the public and media that the OBR’s projections are not laws of physics, and (my personal favourite) setting out a plan and sticking to it for once in their bloody life. “If the government’s pursuit of these goals remains visibly steadfast in the face of shifting predictions,” it argues, “the sense of trust and certainty that follows will stimulate private investment in line with the government’s goals.”1

There’s a lot more in the report, and the panel for the launch event, with recovering senior advisors from three different parties, brought forth multiple stories of people in government accepting defeat without even trying. Some of them concerned civil servants declining to pass ideas up the chain, on the grounds they would get judicial review and they’d be less likely to get yelled at if they did nothing than if they ended up in court. Another – this from LibDem Polly McKenzie – concerned someone telling her that Downing Street didn’t feel like a Labour space as there were so few Labour portraits in it, as if this were not an entirely fixable problem. It’s all terribly distressing.

I have not done the legwork that Phil did to write the report – he knows far better than I – but for what it’s worth I felt a couple of things were missing from the discussion. First there’s the fiscal situation: one traditional route for overcoming opposition is to stuff opponents’ mouths with gold, and that only works if you have the gold to stuff with. Lack of resources for local government also makes it much harder to enforce any measures you do pass.

Another is surely the modern media environment. In the past a government could, for good or ill, ignore the voters that opposed it. Now, between social media and 24 hour news, it has to hear from them all the time. That must be paralysing.

The big one, though, is the current leadership vacuum in Downing Street. Many of the report’s recommendations amount to making a plan and following it regardless of short term distractions. Some ministers, notably Ed Miliband, are doing just that. But the government as a whole is not, because it is not clear what the Prime Minister wants or will approve of. It is not for the Future Governance Forum or Phil Tinline to propose measures to give Keir Starmer an entirely new personality – but it is nonetheless hard to imagine a plan based on leadership without it.

For what it’s worth, though, Phil’s recommended remedy comes in three parts: reject the claim that government is the public’s enemy; reassert democratic political power (that is, stop outsourcing and denying responsibility); and side with the public against its enemies. If this government doesn’t, another, surely, will – and it won’t necessarily agree about who those enemies are.

Fraudsters hate this one weird trick to check numbers aren’t random

In 1881, an astronomer working for the US navy was using a book of logarithm tables when he noticed something weird. Before the invention of computers, those doing complicated bits of maths relied on such books: they were essentially a list of calculations that had already been done, and whose answers you could just plug into your work. What Newcomb noticed was that the early pages of the book – the ones on which the numbers started with the digit one or two – looked worn and grubby compared to the latter pages. That suggested heavier use.

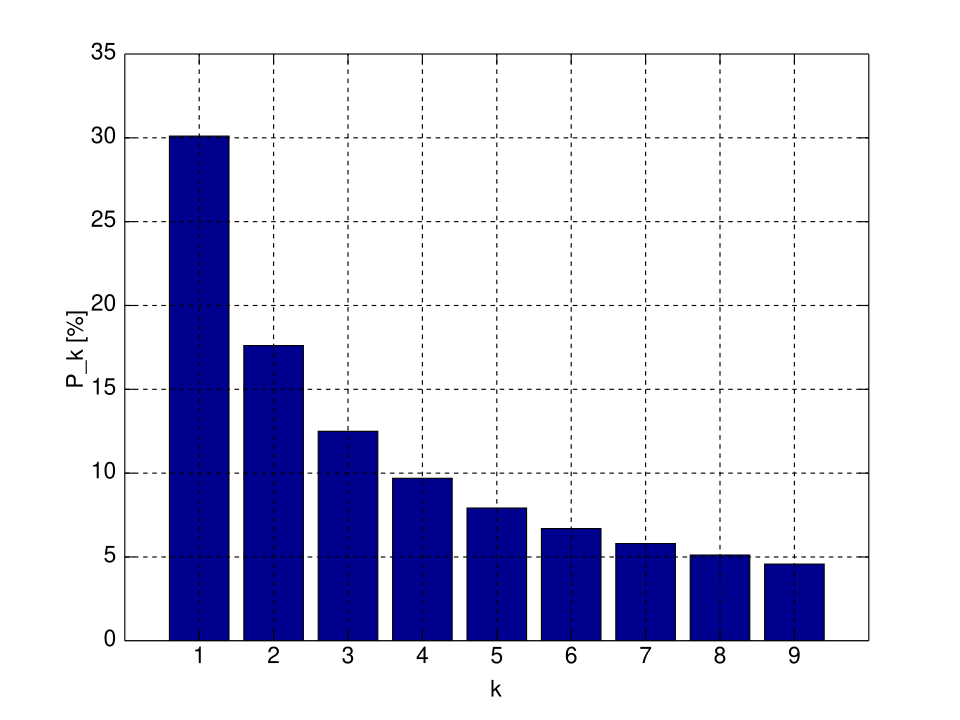

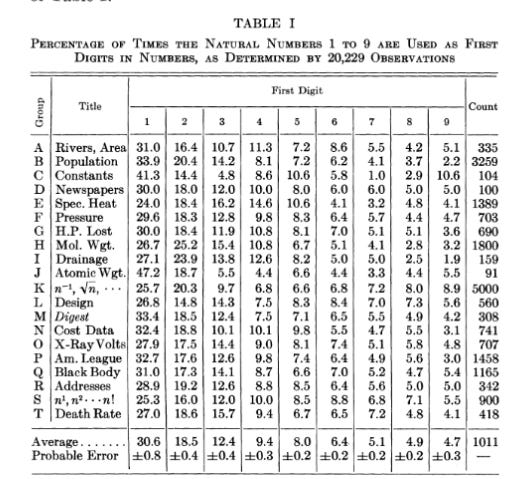

Newcome came up with a theory which seemed, after some time trawling the data, to stand up: that in a naturally occurring set of random numbers, the odds are that the first number will be small. After extensive research, he even put percentages on it:

Half a century later a physicist named Frank Benford noticed the same thing and because the world is unfair got his name attached to it. He did the legwork to gather 20,000 bits of data to prove it, but nonetheless.

Benford’s Law – he more modestly called it the law of anomalous numbers, but it’s also known as the first digit law, or the first or leading digit phenomenon – is not just a curious oddity, but something that’s been successfully used in court. It’s a bit of a thing to get your head around, so I’ll say it again.