“The greatest technician and the greatest poet of British cinema”

Some notes on a forgotten British filmmaker.

This went to paying subs back in March. Tired of all the waiting around for me to let you see behind the paywall? And not even *everything* behind the paywall, only bits and pieces? Well, there’s an app for that:

A few weeks ago while researching the history of the pedestrian crossing, as you do, I came across a delightful 1948 public information film meant to teach unwary pedestrians how to use one. It tells the story of “Mr A, a perfectly straightforward kind of person” who, the voiceover tells us, “reacts quite normally”: the mute, rubber-faced actor pulls a face to show his disgust at the idea of “dried egg for breakfast”; grins to suggest delight at it being pub opening time; looks truly horrified at the mention of his mother-in-law (it was 1948); and so on.

But Mr A has a problem: he struggles to cross the road without nearly getting mown down, in a surprisingly slapstick fashion. The voiceover suggests this might be a good moment to try the newly installed crossing point, marked by belisha beacons and two rows of studs. (The rather less missable zebra crossing would not be invented for another three years.) At first he dawdles, with predictable results; then at last learns to walk across at a normal speed. “It’s no good thinking you can have a sleep or eat your breakfast out there because you’ll soon find yourself in trouble,” says the voiceover accompanying a sequence that is so much more literal than you’re imagining it to be.

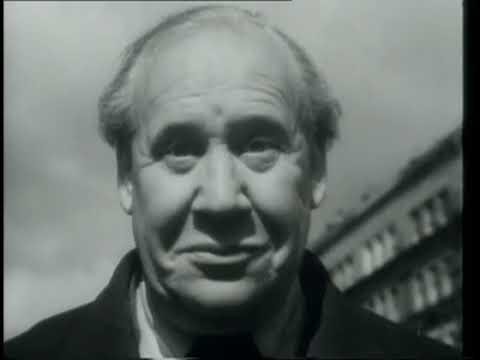

This oddly charming public information film was shown before cinema screenings.1 Its goal was to teach people the purpose of the new crossings by showing someone dimmer than they are learning to use them. This, I learned from the replies when I posted the link to the video on BlueSky, was actually one of several dozen such films made by a little known but much feted writer/producer/director named Richard Massingham. You’d recognise his face. He’s the man who plays Mr A.

Born in Sleaford, Lincolnshire, in 1898, Massingham2 trained as a doctor, and rose to be senior medical officer at the London Fever Hospital. Alas he suffered from hypochondria – not a great choice of career, then, that – so over time his interest in filmmaking, initially a hobby, began to take over.

His first known film, dating from 1933, was a video to promote his own hospital. Five years later, having realised there was no organisation specialising in making public educational films, and presumably realising that being around sick people all the time wasn’t working out for him, Maddingham created his own production company, Public Relationship Films. It arrived just in time for a lucrative business making films under contract to the Ministry of Information.

“In his earliest films,” argues his biography on the BFI website, “Massingham used relatively sophisticated contemporary film-making techniques, borrowed particularly from Russian and European art cinema.” Alas, the needs of communicating vital lessons about health and public safety to a mass audience during wartime required “a simplified approach – though his delight in abrupt cutting and surreal juxtapositions, and an aversion to dialogue, remained”.

In some cases, those lessons were communicated by encouraging the audience to chuckle indulgently at an idiot, played by Massingham himself, for doing something that they would, henceforth, know better than to copy. In 1945’s Coughs & Sneezes, for example, we see a series of practical jokes – people being tripped up, kicked into ponds and so on – and are told by a fruity narrator “they’re a nuisance I agree, but pretty harmless”.3 When Mr A (he isn’t named, but it’s just easier to refer to him as such) is shown repeatedly sneezing on strangers, though, it’s dangerous. He’s pulled aside and shown the benefits of using a handkerchief. In a later film, 1948’s Don’t Spread Germs (Jet-Propelled Germs) he learns how to disinfect his hankie, too.

In other films, the lesson is simply that doing the correct thing can be fun. In 1942’s Five Inch Bather, the same character silently extols the many joys still available to those who preserve water (for, one presumes, the war effort) while taking a bath: he sings, he measures the bathwater with a scale on his foot, he even sails a toy boat. The film begins, delightfully, with shots of elephants in rivers, or a kitten washing his own paw, to show that you can properly wash with entirely different quantities of water.

There are a couple of things I find fascinating about these. One is the performance of Massingham himself as what the Arts Desk’s Graham Rickson describes as “bumbling, childlike everyman”. He reminds me of Mr Bean – although the fact a man making mildly comic public information films was also described by the French archivist and critic Henri Langlois as “the greatest technician and the greatest poet of British cinema” makes me suspect there’s probably also some interplay with the roughly contemporaneous work of Jacques Tati, too.

There’s also something fascinating about seeing the mundane side of life in the period around the Second World War on film. My sense of everyday life from the late 1950s onwards comes from television; before that, from books or films, both of which are more consciously artful and feature less of the sort of incidental background texture you can pick up from TV. Here, though, is the world of austerity Britain on screen in a way I’d not previously encountered.

You can buy an entire volume of 21 of these films from the BFI, because of course you can. I perhaps wouldn’t go that far, but if you’re a fan of factual content repackaged as entertainment – and I don’t mean to make assumptions, but you are voluntarily reading this newsletter – they’re worth spending a few minutes watching online.

Incidentally, my friend Irene, who unlike me actually knows about the history of filmmaking, also compared both Massingham’s physicality and the tone of his humour to Alfred Hitchcock’s trailer for The Birds. That’s delightful, too.

If you enjoyed that, you might also enjoy the bit in this week’s newsletter concerning a different mid-century public information film, named Charley in New Town.

This newsletter is, and will always remain, needs-blind. If you want to read every week but, for whatever reason, can’t currently afford it, you can just hit reply and ask – and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. In contrast to the British state, I’d far rather accept the risk of a few people ripping me off than of those in genuine need going without.

But if you *can* afford it, I’d really like it if you

Fewer than 50,000 homes then had television.

His father, incidentally, was the journalist H. W. Massingham who edited The Nation, a radical weekly absorbed into my own alma mater the New Statesman in 1931.

I am not convinced of this.