The longest and least noticed mountain range in the world

Amazing what you can miss when you’re not paying attention, isn’t it?

This one went to paying subscribers in August…

Every child knows that Everest is the tallest mountain on the planet. Every slightly nerdy child probably also knows that this title has sometimes been challenged by K2, and that both anyway look tiny compared to Olympus Mons, which would get the title easily if someone hadn’t been stupid enough to build it on Mars.

But there’s more than one measure of comparing scale in mountains, so here’s a different question: what’s the longest mountain range?

Wikipedia, as so often, has a helpful chart – which, for reasons I am not entirely clear on, contains the top nine. On that, the Himalayas are all the way down in seventh place, beneath the Rockies and Appalachians, plus a few ranges I was barely even aware of. (In one case, to be fair, it’s because they’re hiding under quite a lot of snow.)1

At any rate: looking at this chart, you’d assume, quite reasonably, that the longest mountain chain in the world is the Andes, the 7,000km range which stretches pretty much the entire length of South America and justifies giving Chile that extremely stupid shape.

But no: I’ve tricked you. Because there’s another mountain range, even better hidden than the Transantarctic. Because it’s under water.

The Mid Ocean Ridge system is a continuous chain of undersea mountains, which begins in the far north, hundreds of miles beyond Iceland. It stretches down the middle of the Atlantic, then turns left through the Indian ocean and passes below Australia, before taking another left turn in the Pacific and hugging the western coast of North America. Along the way there are branches stretching to Chile and Peru, and through the Red Sea to the Levant.

How long the resulting chain is depends on how you count – Encyclopaedia Britannica suggests 80,000km, the US National Ocean Service just 60,000km; I suspect the former counts the branches and the latter does not. Either way, though, it’s an order of magnitude longer than the Andes.

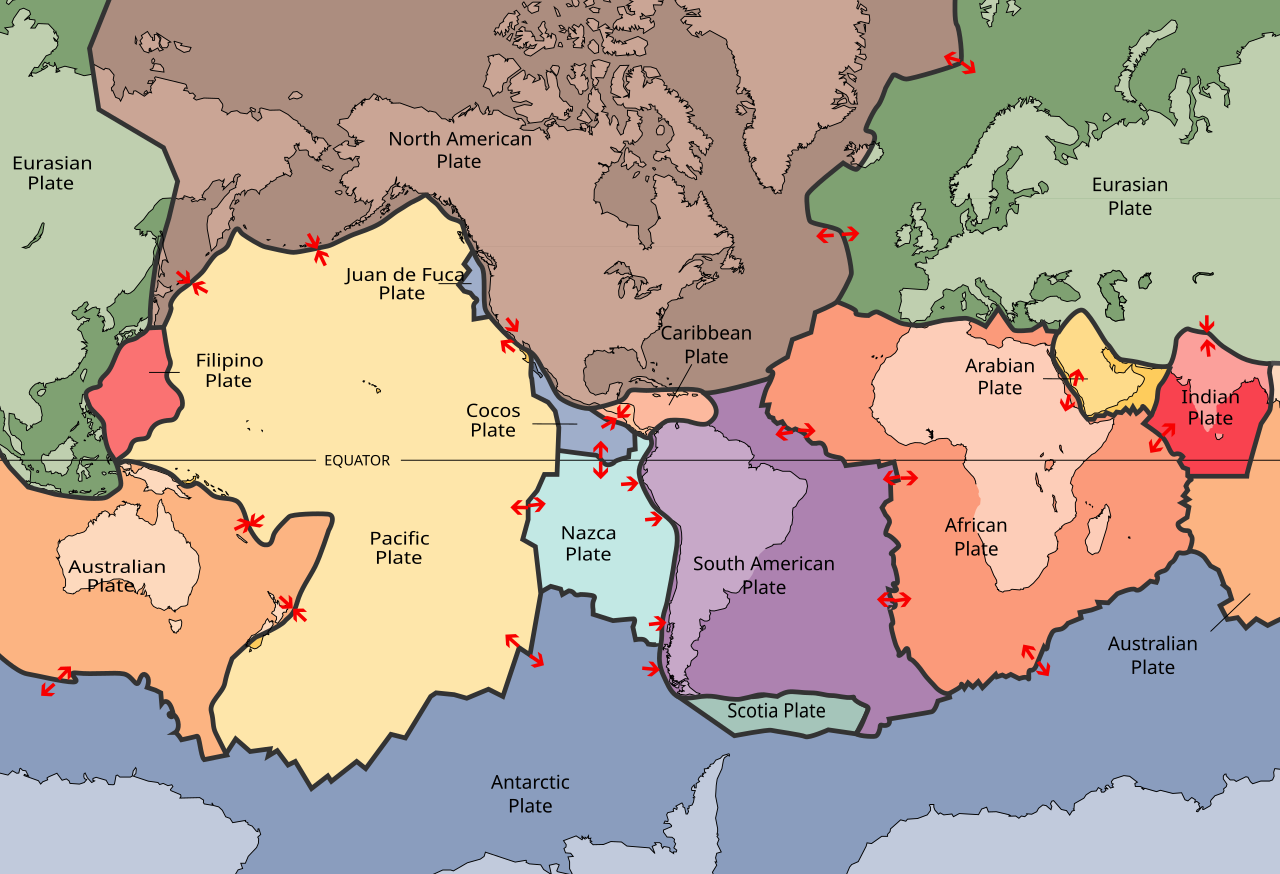

It’s standard practice to describe this chain – probably the largest physical feature of the planet that isn’t an ocean or a continent, which we tend to ignore, because it’s under water – as circling the earth “like the seam on a baseball”. That isn’t just a cute phrase which speaks of how the internet is written in American: it’s also a useful metaphor. This is literally the joins of the planet, the points where tectonic plates meet. To be more specific, it’s the point where plates are pulling away from each other (”divegant plate boundaries”,) causing magma to rise up to fill the gaps, a phenomenon known as “seafloor spreading”.

Where plates collide (“convergant plate boundaries”), you instead get subduction zones, where one plate is forced beneath the other: this too causes mountains on land (Alps, Himalayas), or volcanic islands, like the Aleutians, at sea. But they’re not part of our massive mountain chain.

One could debate, I suppose, whether a mountain chain you can’t actually see is quite as impressive, or even quite the same thing, as one you can go skiing on. But there is one place you can see this one, if you so wish: you just need to visit Iceland. In the Þingvellir National Park, you can stand in Europe and North America all at once – and know you are atop one end of the world’s largest mountain ranges, too.

If you enjoyed that and would like to read more things by me (look, it theoretically *could*) happen, you can press this button:

Oh, and you can also get signed and dedicate copies for my books as Christmas pressies from South London’s finest bookshop, Backstory. A History of the World in 47 Borders here; The Compendium of (Not Quite) Everything – which feels like the book of this newsletter but, in classic Star Wars fashion, actually appeared first – here.

The Alps, in case you were wondering, are not just relatively low by world standards, but short, too: just 1,200km from end to end. As ever, Europe is a lot smaller than we tend to think.