The new cargo cult-ism

One of the most productive sources of bullshit anywhere on the internet. Also: sleeper trains!

About a decade ago, Skins, a show I was far too old to be watching even then, gave its characters Twitter accounts. They’d interact with each other, make stupid jokes and occasionally comment, gnomically, on this week’s plot. It was clearly meant as a clever way of adding another layer to the fiction, of assisting the characters to live rent-free in the audience’s mind.1

I found it deeply unnerving. You could, in theory, chat to these characters in the same way as you could with your friends, or newspaper columnists you didn’t like, or Stephen Fry. If you didn’t know what they were, and had only the evidence of their Twitter feed to hand, you could plausibly mistake them for real people. But they weren’t real people: their feeds had more in common with a Dickens novel than your own social media, and the actors you might picture weren’t even the ones behind the keyboard. A couple of years later, Charlie Brooker wrote an episode of Black Mirror, in which a tech company provides a woman with ever more realistic simulacra of her dead boyfriend, only the real-er he seems the more terrifying it becomes. Which suggests I wasn’t the only one unnerved by all this.

All this is an example of the “uncanny valley”, the theory that human emotional engagement with a thing increases with its resemblance to humanity… until it gets too close when suddenly that thing becomes terrifying. (The “valley” is the dip in the graph.) But I think there’s another reason it’s unnerving, too. Stuff that shares the form, but not the content, of other stuff is one of the most productive sources of bullshit anywhere on the internet.

The problem isn’t new, of course. Consider the “cargo cults”, which began to emerge on remote islands in the late 19th century and went into overdrive during World War II, when allied forces set up temporary bases as staging posts. This was in some ways a pain in the arse for the locals, as the appearance of foreign military forces have been throughout the centuries; but it did mean the arrival of all sorts of exciting new goods previously unavailable to those Pacific islanders, often airdropped by friendly planes. After the USAF and friends shipped out, those goods stopped dropping – so some islanders began mimicking the behaviours that had seemed to bring them in the first place, fashioning rifles out of wood for makeshift parades, lighting torches on landing strips, even making headphones from bamboo. By replicating the form of the air base, they hoped to bring forth its content, too.

In some ways all this is rather clever – an example of how, in religion and ritual, the very first inkling of scientific method can be seen. But the existence of cargo cults has been providing columnists with patronising drop intros about groups that don’t share their sophisticated understanding of the world ever since.

And once you’re aware of cargo cult-ism, you start noticing it everywhere. When people like Jacob Rees-Mogg or my old friend Daniel Hannan pepper their speeches with references to dead Romans, it seems like an attempt to assume the shape of very clever and thoughtful people. Scratch the surface, though, and there’s little actual intellectual enquiry going on – such rigid ideologies don’t allow for it. They genuinely seem to think that this mode of speech is what being clever is. (Rees-Mogg, as someone close to me delights in pointing out, is not that posh and has extremely bad Latin.) 2

Then there’s the realm of conspiracism, where every text seems to come accompanied by a blizzard of references, and every response to criticism is met with exhortations to “do your own research” or tweets reading, “Evidence?” As far back as 1964, in his foundational essay The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Richard Hofstadter noted that this mindset was “nothing if not scholarly in technique”. One conspiracist text he highlighted “contains no less than 313 footnote references”; another, “one hundred pages of bibliography and notes”.

In all these cases, I think, what we’re looking at is the confusion of form and content. The conspiracists believe that footnotes are more than just pointers to where further enquiries can take place, but an inherent source of truth in themselves. In the same way, the Hannans of the world think that intellect lies in the classical references, not the process of open-minded inquiry that led one to acquire them. They’ve confused the signifier for the signified.

And then there’s the thing that got me thinking about all this in the first place.

There’s a TikTok-er called Donna Dickens, who has more than once attained main character status for her fervent assertions that the Roman Empire didn’t exist. Here’s the latest:

Downthread, she compares it to genuine texts messed up by the church, or museums’ occasional tendency to simplify, or even – let’s not sugar coat this – lie.

There are real examples of such things taking place, and posts and videos in which reputable historians discuss them. (We all know the scale models of dinosaurs you get in museums aren’t real: but many of the dinosaur skeletons up the corridors are reproductions, too.) And, it’s true, there are relatively few original texts left from the Roman era: much of what we have comes from copies of copies. Such things have formed the basis of other insane theories, like Anatole Fomenko’s History: Fiction or Science?, which argues, essentially, that everything before about 1000AD was a lie, copied and pasted from somewhere else, probably by a monk, and that all good things actually come from Moscow. The seven volumes of that book have a lot of footnotes.3

But they’re quite obviously nonsense. The reason we rely on copies is because 2,000 years is a long time, and stuff literally decays. Among the evidence we have for the existence of Rome is the existence of Rome, a very old city with some extremely old things in it.

The reason stuff like this can find an audience is partly, yes, because “everything you know is wrong” will always be a compelling story, but also I think because it takes a form that looks real. There are plenty of history channels on YouTube and TikTok, whose general vibe is not a million miles away from Dickens’. Often they do point out that institutions have lied, or that everything we’ve been taught about a battle actually comes from two third-hand copies of a text commissioned by its winner. The resemblance between this madness and “real” history is obvious.

But the differences sometimes aren’t. Can you immediately tell, when watching a TikTok or reading a tweet, whether you’re reading the product of a subject expert in the middle of a PhD; or whether they’re just spouting half-remembered nonsense from some other random’s YouTube video? In form, these things may look the same. In content, they’re entirely different. The cargo cultists have copied a style, and mistaken it for a methodology.4

This is an unnervingly large chunk of the internet now. Sometimes, as with the theories of Donna Dickens, you don’t have to push hard to see that what you’re looking at isn’t real. Sometimes, as with the Twitter accounts of fictitious Bristol teenagers, the differences may be a little harder to spot.

What worries me is how often we might not notice them at all.

Map of the week

Around the time I wrote that post, which paying subscribers got to read months ago, I enjoyed one of the most fun experiences you can have while not getting enough sleep – no, hang on, I’ll rephrase, one of the most fun experiences you can have, while not getting enough sleep, which also involves a train. I travelled on a sleeper.

Today, depending on how you count, Britain has either two, three, or six sleeper services. There’s the Night Riviera, which runs between London Paddington and destinations in Devon and Cornwall. Then there’s the Caledonian Sleeper, which is actually two different trains (Lowland and Highland), which split to serve two (Edinburgh and Glasgow) and three (Fort William, Inverness, Aberdeen) destinations in Scotland respectively. These are, you will note, routes which run between the capital and the farthest flung corners of this island, and even then there’s a lot of slow-running and waiting around involved, in a transparent attempt to make four or five hour journeys last all night.

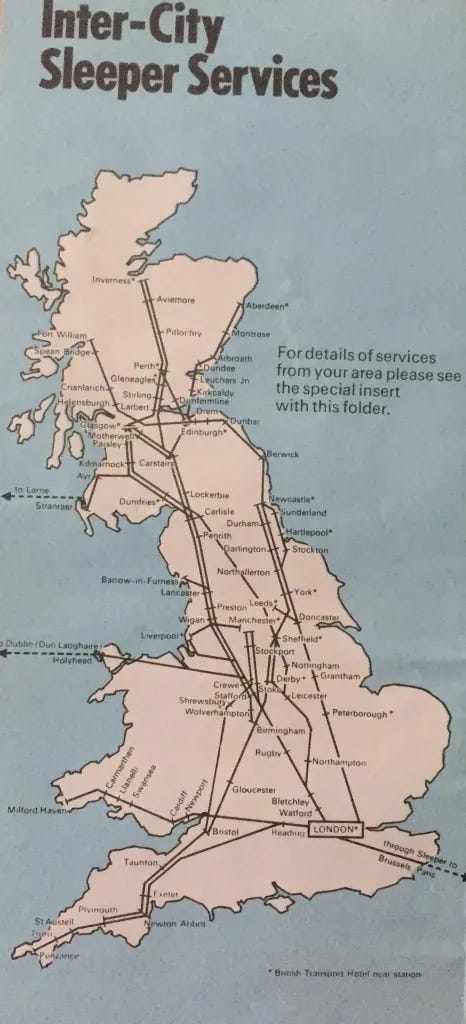

This may be why there aren’t more sleeper trains – this island just isn’t big enough to justify them. But that didn’t stop the network running them in the past, as this map of British Rail sleeper services in the 1970s shows:

Asides from the services running today, the network used to provide trains from London to Newcastle, south Wales, Holyhead (for Dublin) and Dover (for the continent, via the Night Ferry service to Dunkirk). There were more destinations in Scotland and Northern England too, and cross country routes that didn’t go near the capital; this ancient-in-internet-terms thread on Rail Forums suggests there were “night services” – that is, regular trains that ran overnight, without special sleeper carriages – too.

So what happened? The Night Ferry stopped running in 1980, but even if it hadn’t it’s hard to see an 11 hour train from London to Paris remaining competitive in a world in which Eurostar can do it in two. Faster trains on other routes are no doubt a factor, too. But another one seems to be privatisation: a state-owned British Rail would happily run a socially useful service at a loss, private train operators won’t.

That said, I do wonder if there’s a bigger market for these services than the network currently allows for: the still extant sleeper services aren’t cheap, which points to pent up demand. Sure, it’d mean up-front investment in rolling stock, and a lot of dawdling to pad out journeys to make them take all night. But there’s nothing more romantic than going to bed in one city, and waking up in another, is there? Even if you don’t, in fact, sleep much along the way.

A bonus map, from one of the very earliest editions of this newsletter: some maps of existing and proposed night trains across Europe. Cool.

Self-promotion corner

The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything goes out every Wednesday at 4pm. In this week’s edition I wrote about how it’s time to weaponise NIMBYism; the 80th anniversary of the Bethnal Green tube disaster, the single greatest catastrophe ever to happen on the London Underground; and a map showing that all roads really do lead to Rome.

If you’re enjoying these weekly extracts from the archive, then why not become a paying supporter? For just £4 a month or £40 a year, every Wednesday afternoon you’ll get a bit on politics, some diverting links, an article on something from history/geography/language/whatever I’ve been obsessing about this week, and the map of the week. And for less than a pound a week, too!

Click this button, in fact, and I’ll give you 5% off a year’s subscription and a copy of my book Conspiracy: A History of B*llocks Theories & How Not To Fall For Them, when it’s published in paperback next month.

BUT: we’re all broke right now. If you can’t currently justify paying for some nerd’s substack (unemployed, underemployed, impoverished student, and so forth), just hit reply and I’ll give you a complimentary subscription, no questions asked. I am literally giving it away.

Or here are some things you can read now without giving me a penny:

“The first time as farce; second time also as farce.” How the Lockdown Files - a name the Telegraph is using because “Matt Hancock’s message history” sounds deeply undignified - only confirm every suspicion we ever had about the pandemic government.

"Oh my god can this man not hear himself? Does he simply assume the rest of us can’t join the dots?" On how Rishi Sunak has realised single market membership is great, providing you're Northern Ireland.

If you want to hear me get slightly hysterical about this story, I was on Adrian Chiles' 5Live show on Friday doing just that. (I'm on for the first hour, that bit's somewhere towards the end.)

A lot of nonsense I’ve written about Doctor Who, which you can find here.

It didn't work. This was the last and, so far as I can tell, by far the least popular of the show's iterations, and they cancelled it shortly afterwards.

I umm-ed and ah-ed about whether to mention other, more deliberate examples here: when corporations go big on Pride or CSR while continuing to otherwise behave appallingly; when Boris Johnson talked about levelling up or Ed Miliband put “controls on immigration” on a mug, it’s clearly an attempt to win points by talking about something without actually having to do it. (“Always dispose of the difficulty in the title,” as Sir Humphrey once said. “It does less harm there than in the text”)

This, though, is not quite the same thing because it’s intentional. This deliberate use of form to hide content is sort of tokenism, sort of [X]-washing, and sort of good old-fashioned bullshit… but I’m not sure there’s a specific word for doing all those things at once. Can you? If not, I move we make one up.

You can find more of this sort of thing, in Conspiracy: A History of Bollocks Theories & How Not To Fall For Them, my recent book with Tom Phillips. Extract from the start of this exact chapter here.

This line was shamelessly stolen from Tom’s comments when he read the first draft. I couldn’t, in good conscience, steal this one too, but I liked it so much I wanted to use it anyway: whatever the similarity in vibe, the real historians’ PhDs “are not actually in Tea Spilling or Totally Destroying People Online”. Tom is a great man, which is one reason we wrote a book together, and you can read his own newsletter here.