The Second Time Around

This week: it’s English local government reform a-go-go! Also: a map of London’s first, long-forgotten Overground Network; and two charts summing up all US presidential history.

In 1966, as readers of this newsletter are unusually likely to know, the Labour government of Harold Wilson decided to reorganise the mess of English local government structures left over from the Victorian era. For nearly eight decades, England had been covered by a dizzying array of borough, urban district and rural district councils, with a tier of county councils sitting above them, and a group of special county boroughs excluded. Who was responsible for what in any given area was not always immediately clear.

The Redcliffe-Maud Report of 1969 proposed to sweep all this away. Areas based on Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham would be reorganised into bigger boroughs beneath a metropolitan council, on the same sort of basis on which London had been reorganised in 1965. The rest of the country would consist of unitary councils, combining a major town and its hinterland, on the grounds that the two were interdependent and it was silly to govern them as if they were not.1

Some of these would be recogniseable successors to existing counties, with bits lopped off or added on, but many would be either bigger or smaller areas. The point was to replace a system of territorial units devised for the needs of local administration and anti-Viking defence policies in the 10th century with one fit for the economy of the late 20th.

This didn’t happen, obviously – preventing it was, indeed, a part of the platform on which Ted Heath’s Conservatives won the 1970 election. Metropolitan councils (more, but smaller) happened in 1974, were abolished in 1986, then reinvented, gradually in the 20th century. Further rounds of reform in the late 1990s, late 2000s, and early 2020s have introduced more and more unitary councils in large chunks of England – but in many places the two tier system remains.

For some time now, there have been growing mutterings that it might be high time for a rethink. One big motivation is money: thanks to the sterling work of George Osborne in devolving the cuts, combined with the sterling work of pretty much everyone in not reforming social care, councils don’t have any. As far back as 2011, local government leaders were fretting about the “graph of doom”, which showed their shrinking projected budget being overtaken by the cost of statutory services – the things councils legally have to provide (children’s services, adult social care) – some time around 2022. That is, you will notice, in the past, which is one reason councils keep going bust.

At the same time, groups like the Centre for Cities have been pushing for reorganisations based on city/hinterland regions, not a million miles away from the Redcliffe-Maud plan, on the strikingly similar grounds that these would be more economically rational units.

And now, it’s happening, sort of. According to this week’s Sunday Times:

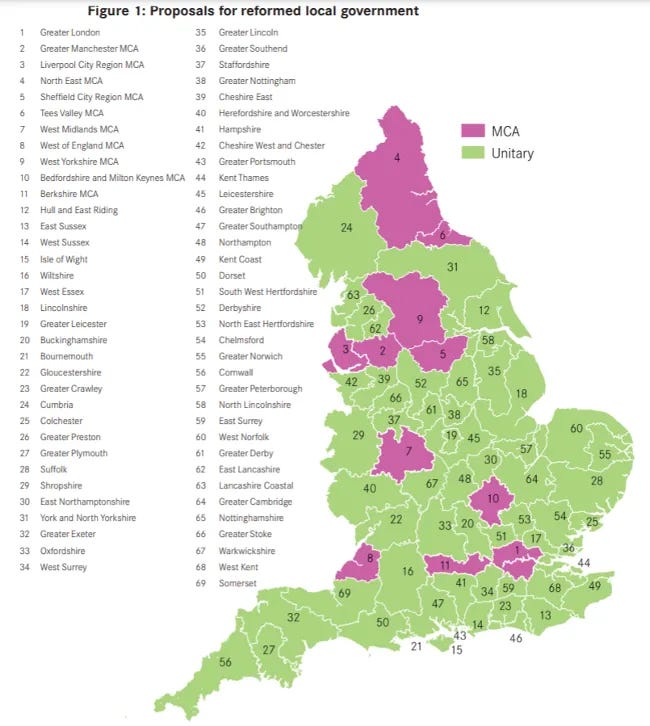

Dozens of councils will be abolished in the biggest overhaul of local government in more than 50 years under plans being drawn up by ministers.

Essex, Kent, Surrey and Hertfordshire will be among the counties set for radical changes to the way they are run, with the promise of more powers and money from Whitehall. Norfolk and Suffolk will also be restructured, with their district councils being abolished and merged into new unitary authorities.

In all, the paper reports, ministers have identified 10 areas of the country that are “open to reform”, where existing councils will be replaced by unitaries with 500,000 people or more: the suggestion is that change will not be forced on places that don’t want it. Whether it’s a coincidence that all those named are in the relatively affluent Home Counties or East Anglia, it’s not entirely clear. (Perhaps they’re just the ones reporters had managed to phone before their deadline.) A white paper on English devolution will be published in the coming weeks.

There are other problems with the two-tier system that this could plausibly address. It would prevent councils from passing the buck, blaming their failures on other levels of government. It would also be more comprehensible to the public – no more misplaced shouting at the district about highways, or the county about bins.

On the other hand though, it might suck in a lot of political and administrative energy in search of a saving that is not, in the scheme of things, that big. (The £3bn it’s projected to save over five years is enough, assuming it happens at all, to keep the NHS going for about a week.) History suggests that a lot of people who think their council is rubbish might suddenly find themselves passionately in favour of it, and vote accordingly. Running cities and their hinterlands as single units sounds great – but the interests and priorities of urban and rural voters don’t always align, and there must be a risk in some areas of the latter blocking the kind of projects necessary to boost the former, and thus stunting the local economy.

But the biggest issue, surely, is that when people complain that the new councils are distant and remote from their daily lives, they won’t be entirely wrong. Half a million is a lot of people – not far off the populations of Malta, or Wyoming, which aren’t especially notable places, but aren’t exactly local councils, either. While it may make sense to run transport or economic strategy or social care at that level, there are surely other things councils do – culture or place-making; the stuff one might think of as hanging baskets, rather than bins – that should happen at a far more local level, of town or village or neighbourhood.

The story of English local government reform for decades has been one of very slowly coming around to very obvious things that we actually knew all along. It must be at least possible that “we need a layer of government that reflects the places in which people actually live” will be a lesson we learn the same way.

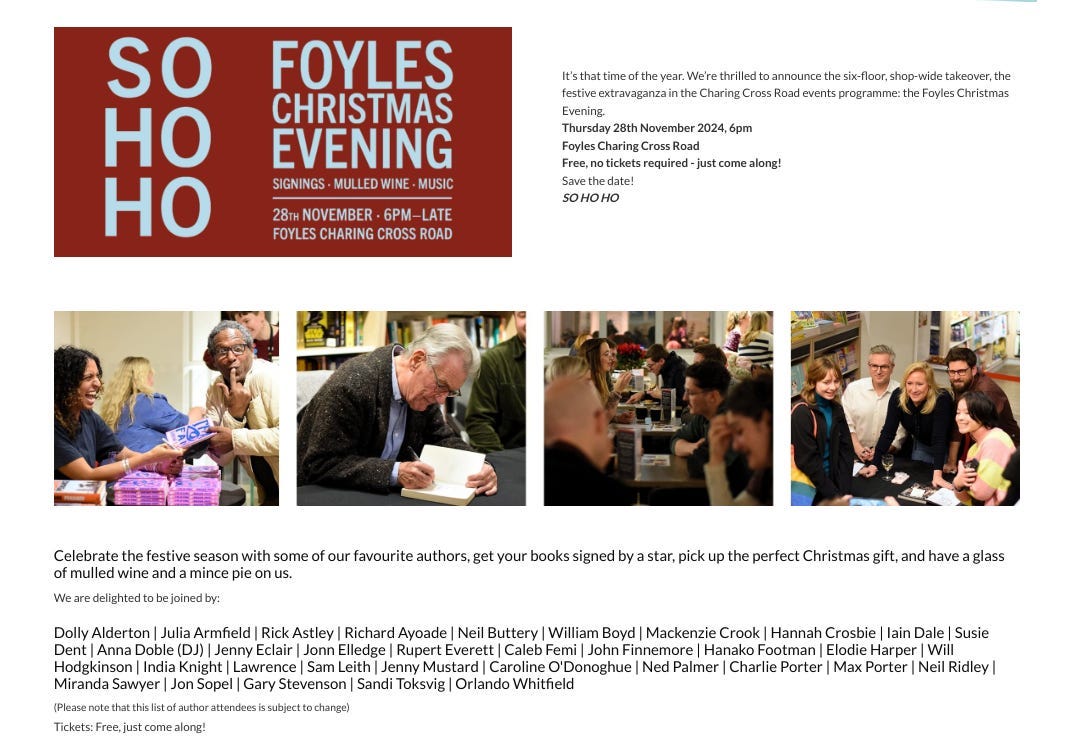

Mince pies, mulled wine, Rick Astley and me

Just a reminder that if you’re at a loose end in London’s glamorous central London district tomorrow, it’s the Foyles Christmas Evening. I am genuinely terrified that no one will want to say hello to me except my mum (hello, mum!) and I’ll look bad in front of Sandi Toskvig and William Boyd, so please do swing by if you’re about:

I imagine I’ll be on a corner somewhere, looking sad that they wouldn’t let me sit with Miranda or something.

The entirety of US presidential history in two charts

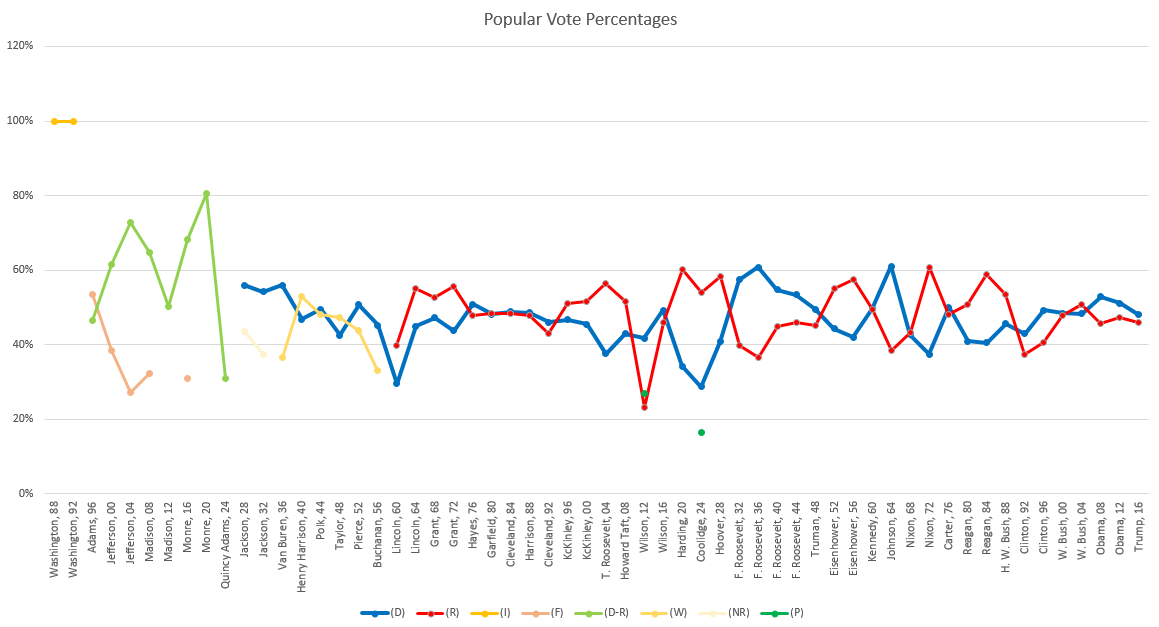

American politics. That’s something we all want to be thinking about even more right now, yeah? Okay look I promise I’m not going to keep at it after this, but here’s one last thing I found on my travels through presidential election history the past couple of months. It’s a chart of popular vote share by party, all the way from 1788 to 2016. (It dates from 2019 when, we are left to assume, whoever it was who made it lost all hope.)

This is, essentially, a history of the US party system – which has changed a lot and was often, as you’ll have noticed during several of my essays on half forgotten presidents, confusing – in one image. And there’s loads of delightfully mad stuff here.