The Streisand Effect

Also this week: how many colours can a metro map have? And a gif of the absurdity of English government.

In 2003, Barbra Streisand, the actress and singer who’d recently found fame as the face of South Park’s “Spooky Vision”, sued a photographer for violation of privacy, in an attempt to suppress a photograph of her house.

The focus of Kenneth Adelman’s “Image 3850” was not actually Streisand’s Malibu mansion at all, but the cliff on which it sits. It was one of around a dozen homes visible in the image, which was in turn just one of around 12,000 photographs, taken from a helicopter as part of the California Coastal Records Project and intended to document coastal erosion. Image 3850 had also only been downloaded six times, prior to Streisand’s lawsuit; two of these were by her lawyers. But so annoyed was the actress that her home was visible that she was determined to suppress the image anyway, and sued, for $50m.

You can probably guess the rest. The case was reported by the media, leading nearly half a million people to go looking for Adelman’s site so they could look at Streisand’s house. “If her goal was to have a chilling effect on future voyeurs,” one Washington DC communications consultant said at the time, “the success remains to be seen. If her goal was privacy, she blew it.”

Soon enough it turned out she hadn’t even managed the chilling effect bit: the lawsuit was dismissed, and Streisand ordered to pay Adelman $177,000 in legal fees. A few months later, Mike Masnick, reporting on a similar case, gave the phenomenon a name. “How long is it going to take before lawyers realise that the simple act of trying to repress something they don’t like online is likely to make it so that something that most people would never, ever see… is now seen by many more people?” he wrote for TechDirt. “Let’s call it the Streisand Effect.”

Two decades later, it seems that it isn’t only lawyers who should be wary of the Streisand Effect. Europe woke up on Friday morning to discover that Twitter – the social media site which is still, despite itself, the one all the hacks hang out on – was no longer allowing retweets of or replies to tweets containing links to Substack. The following day it blocked URL shorteners like bit.ly, too, warning anyone who clicked on a link that led to Substack that it had “been identified... as potentially spammy or unsafe”.

Why Twitter had done all this was not exactly clear: Substack’s decision to launch a Twitter-esque new “Notes” function was suspected, but since no one at the bigger company, up to and including Elon Musk, actually bothered to comment, who even knows? At any rate, by Saturday night, it had all been reversed. Twitter once again treated Substack links no differently to those to anywhere else on the internet; light had returned to the world.

If all this was meant as a warning shot, though, I’m not sure it was very effective. A number of normally Musk-friendly writers, notably Matt Taibbi, watched the world’s richest toddler threaten their income and changed their tune; Substack Notes, which I’m not sure anyone had been paying any attention to before, got a load of enthusiastic and motivated beta testers; and, anecdotally, Substack sign-ups went through the roof. I’m not sure what’ll happen if Musk and Twitter pull all this again, which they might; but as things stand the main result is that a lot more people are aware of both the fragility of the Twitter ecosystem and the possible alternative Substack represents.

All of which is a long way of saying to all our new subscribers: thanks for joining us. It’s great to have you here.

The fifteen colour problem

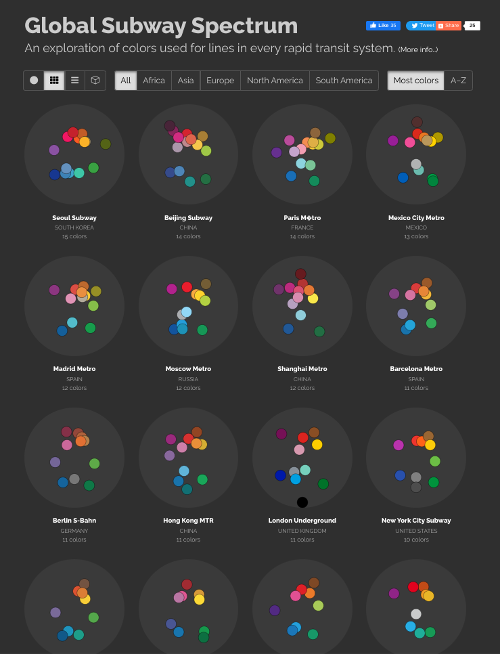

A few years ago, a Chicago-based designer named Nick Rougeux published the “Global Subway Spectrum: An exploration of colours used for lines in every rapid transit system”. It allowed you to see every colour then used by every metro map in the world on a single wheel:

Or as a grid:

You could see the colours used by individual cities, too:

It’s a lovely project, from which I learned a variety of interesting things. It highlights, for example, that there are a lot more metros in Europe and Asia than the Americas or Africa, which I already knew but which it was useful to quantify. It also shows that not all colours are equally popular, so that while the metro maps of the world are covered in lines of red, blue and green, there are slightly fewer yellows and purples, even fewer pinks, browns and oranges, and hardly any greys at all. Only two cities in the world had lines coloured black: Bilbao, and London. This perhaps explains why the Northern Line is so cursed.

Perhaps the most important thing it highlights, though, is that there’s a limit on the number of colours a map can comfortably contain. The average human eye can be expected to distinguish between, say, light blue and dark blue, or violet and magenta; but include more than a couple of a similar shade, and they stop being something you can identify by sight. The result seems to be a hard cap on the number of colours a map can use and still be read at a glance. At the time Rogeux did his work, at least, only 12 networks used more than 10 colours, and only Seoul used as many as 15. That was a few years ago, of course, so things may have changed. But I doubt that they have changed much.

London currently uses 11 colours for its Tube lines, plus another four (DLR, Overground, Elizabeth and Trams) for services shown in the same style on its Tube & Rail Map. We learned a few weeks ago, though, that money has been set aside to split the Overground into a number of individual lines, each with their own identity – and thus, one suspects, their own visual branding. I personally think that should mean replacing one colour with seven, realistically the most likely number at present is six.1

That will mean five additional colours – which, if you’re counting, would bring us to 20. It seems extremely unlikely that a map containing 20 colours will still be legible at a glance: after all, it’s already been forced into using four different shades of green. So what is to be done?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.