This went to paying subscribers back in January. If you feel embarrassed that you’ve gone three months without being able to regale your friends and loved ones with this story – and quite frankly you should – you can join them here. What the hell, the sun’s out so here’s a special offer:

Between 1853 and 1870 the prefect of the Seine, the man known to history as Baron Haussmann, set out to remake Paris. Out went overcrowded and unsanitary medieval neighbourhoods; in came wide boulevards, new parks and squares to provide access to green space, and an entirely new water and sewage system. Haussmann’s work was criticised – for its careless approach to the city’s history and its heartless approach to its residents; for the suspicion the boulevards were not merely a gift to Paris but an attack on the Parisians, an attempt to prevent yet another bloody revolution by creating roads too wide for barricades. But it reshaped Paris, and created the city we’re familiar with today.

London has generally eschewed such grands projets in its street plan. There were the Embankments, of course – Victoria in the east, Chelsea in the west, Albert across the river – designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette to replace marshes with new roads and flood defences, not to mention convenient places to keep a sewer or a Tube line. There was Shaftesbury Avenue, built from 1877 and clearly influenced by Hausmann’s work in being both a wide new thoroughfare and an aggressive act of slum clearance. But new urban road plans have frequently ended up as little more than stubs, because of the fact residents kick up a fuss until they go away again. Even after the Great Fire, Christopher Wren’s extensive rebuilding plans fell by the wayside because the locals had rebuilt most of the city before he’d made it as far as his drawing board.

There was one such scheme that did come off, however, and which still affects the shape of the city today. It was, in a manner that feels telling of the difference between Britain and France, privately built. And it got around the “We don’t do that sort of thing here” problem in the same way the M25 would later: by being built outside the city altogether. One of central London’s main roads, a traffic-smogged chasm that anyone who has so much as visited the city has almost certainly been to, was originally built as a bypass.

Oh, and its intended users were mainly expected to be cows and sheep.

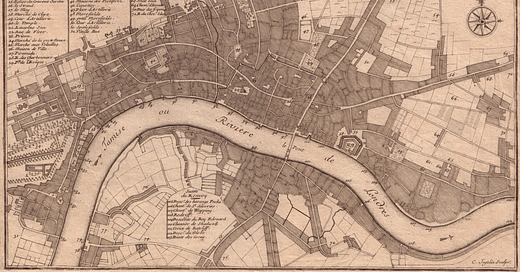

As late as 1700, London ended around St Giles, today the site of Centrepoint and Tottenham Court Road station. In the 18th century, though, those who owned land to the capital’s north and west, or on the royal hunting ground between Westminster and the Oxford road, began developing fashionable new residential suburbs: Soho, Mayfair, Marylebone, Bloomsbury.

The only slight problem was that the Oxford road was already being used heavily as, well, a road. What’s more, since a large chunk of England’s agricultural land lay to the west of London, while its main meat market on the north side of the City1 lay towards its east, much of the traffic was composed of farmers driving their flocks and herds to market.

And so those wealthy landowners – wary, one assumes, of leaving the Georgian equivalent of Foxtons trying to persuade Lord Bridgerton to disregard the pig smell as they showed him around his new townhouse – came up with a plan. They would obtain an Act of Parliament to give them the right to build a new toll road, comfortingly far away across the fields north of the city. The new route would run east from one rural village, Paddington, to another, Islington, where it’d meet the Great North Road. It would be wide – upwards of 40 feet, with rules to ensure no buildings within 50 of the edge – making it an ideal drovers’ route (herds of livestock not being famed for their ability to walk in a straight line). And, at its eastern end, it’d be a short trip down what is today St John Street to Smithfield Market, which is very nice so I’m sure the cows, sheep and so forth had a lovely time.

Even the 18th century had nimbys, of course, and inevitably there were complaints: the Duke of Bedford, in particular, objected to the view of fields from Bedford House in Bloomsbury being interrupted. Nonetheless, royal assent for the Highgate & Hampstead Roads Act, which provided a legal framework for this and several other turnpikes just north of London, was granted in 1756, and construction of the new road began.

It was a huge success. The drovers taking their livestock to market, from whence they would presumably go off to live happily ever after on a lovely farm somewhere, ceased to go through London: instead they went around it, paying a toll to the Marylebone or Islington trusts for the privilege. So useful did the road prove, indeed, that just five years after it opened it was extended, from Islington to the City proper at Moorgate. It was now possible for horse drawn traffic from the shires to reach the City of London and London Bridge without clogging up Oxford Street or High Holborn on the way. Even the Duke of Bedford changed his tune, building his own private road north to reach the new road – the north-south artery that today links Aldwych to Euston.

For a long time, indeed, the New Road from Paddington to Islington – the Ronseal-esque name by which the road would be officially known for its first century – marked the sort of psychological border of London, in the same kind of way the M25 does now. In-fill development was built to reach it. During the canal mania of the early 19th century the Regent’s Canal, which connected the Grand Union Canal at Paddington to points east, was built with basins (Battlebridge, Wenlock, City Road) lining the road’s north side.

And then the railways arrived. Companies serving destinations to the east and south of London drove their new lines right into the urban area, with scant regard for the poor residents they dispossessed; those coming from the west and north, by contrast, tended to respect the capital’s existing geography. That is why, to this day, Kings Cross (1852), St Pancras (1868) and Euston (1837) stations line up along the road, with Marylebone (1907) a mile or two distant: they were effectively plugging into the existing transport network, made up of a massive road with canal access. So useful was this artery that London’s first regular bus route – a horse drawn omnibus, from Paddington to the City – used the road, too. So did the world’s first underground line, the Metropolitan Railway, built by digging a trench under the road and then recovering it in the early 1860s.

The New Road hasn’t been called by that name since 1857 – today it’s known as, from west to east, Marylebone Road, Euston Road, Pentonville Road and City Road – and even by then it had long ceased to be the northern edge of London. Today, indeed, the row of stations to its north perversely means it feels like central London, even though they were only built there because it was barely London at all. (The road does, however, remain the border of the congestion charge zone and thus, on some definitions, of central London today.)

But still, when you step out of Kings Cross or Euston stations, take one look at the horrendous traffic-smogged artery before you and decide to get away as quick as you can, remember that you are looking at a bypass built on green fields – even if it hasn’t seen a cow in ages.

As well as the usual sources for such things, Brian Turner’s piece for Camden Guides was very helpful in putting this together.

And finally…

A reminder that my book A History of the World in 47 Borders is, bafflingly, the non-fiction book of the month in both Waterstones and Foyles. If you’re in Liverpool or thereabouts, you can hear me talk about it with Neil Atkinson of Anfield Wrap fame at Waterstones Liverpool One this Monday night.

A note for non-London readers. The reason “City” is capitalised here is that there is a difference between the City of London (the original Roman city, the square mile, the skyscraper-strewn financial district to the east of the centre) and the city of London (all of it). I’m not claiming this makes sense, but these are the rules.