Where Did It All Go Right?

This week: oh bloody hell fine I’ll write about the Tories. Also: a play about the man who made the Tube Map; and the surprisingly decent presidency of Chester A. Arthur.

Does any of this actually matter, Podmasters supremo Andrew Harrison asked me on Tuesday’s edition of Oh God, What Now? after I somehow got lumbered with the job of explaining the Tory conference to the world. Or is it all just a symbolic exercise?

One one level – no, it doesn’t matter. The Liberal Democrats, true to their name, set policy through democratic votes at conference. The Labour conference does a bit of that, but the leadership doesn’t feel especially beholden to the results. The Tories, though, make absolutely no pretence of it: conference is a rally and a fundraising exercise; members are there to applaud politely, open their wallets and otherwise shut up. Yes, it is a symbolic exercise. It always is.

One another level, though… No, it still doesn’t matter, because the party just had the worst election result in its history and seems as far from power as it’s ever been. The current leadership contest, the world’s most off-putting beauty parade, may be fun for the party and for those of us who enjoy the chaos; but it probably won’t have much of an impact on the wider world. That’s not why I’m not in Birmingham this week – the actual explanation is a more prosaic “no one’s paying me to go” – but it is why I’m not that bothered about it.

The only moment at which I felt a twinge of regret that I wasn’t there in person came while reading Adam Bienkov’s reports from a fringe event entitled, “What went wrong?” A couple of the clearer-eyed contributors – generally younger; disproportionately likely to be readers of this newsletter – tried to explain that the party had lost the under 50s and was now widely loathed. But recovering leadership candidate Mel Stride seemed to suggest that the polls would swing back by default; while Danny Kruger, campaign manager for frontrunner Robert Jenrick, suggested that the way to win back the young was to “win a culture war”. (So, not higher wages or more affordable housing, then.) Party members in the audience, meanwhile, suggested that the problem was a failure to sell what a good job the party had done in government or, alternatively its “anarcho-tyranny thing”. Sure.

All of which means the leadership election seems to be happening in an alternative reality in which the last 14 years were in some way fine. Of the two more mainstream – let’s not go as far as centrist – candidates, what Tom Tugendhat lacks in experience he makes up for in being a personable clean skin with a compelling biography. (He was in the army, you know.) James Cleverly, meanwhile, is prone to foot-in-mouth syndrome, and – this is niche, but – used to work in media sales, and you can tell; but he also held two of the great offices of state, and not only didn’t mess up but seems to have been liked and respected. Either would seem to make plausible leaders of the opposition.

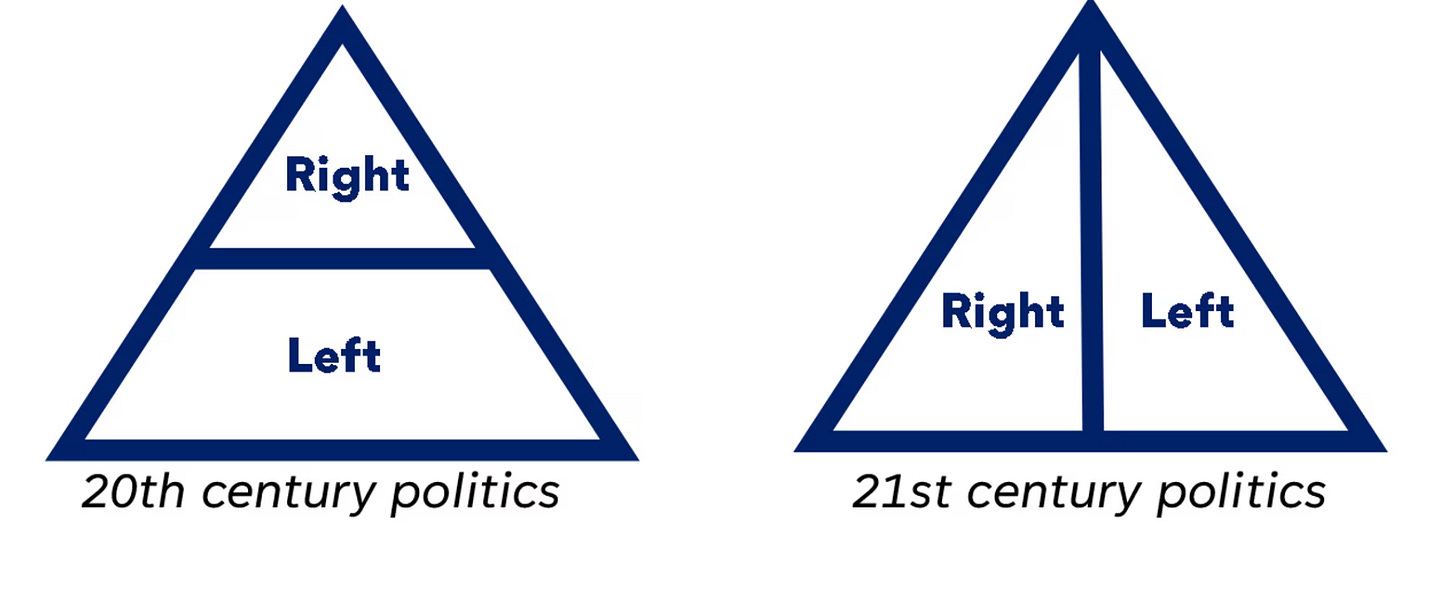

We aren’t talking about them, though, because the party is unmoved by their talents. We are talking instead about Kemi Badenoch, a woman who could make enemies in an empty room, and blames the press for the crime of accurately reporting the words that come out of her mouth. She would likely win in a landslide if she made it to the last stage of the contest when the members get to vote; but she probably won’t get that far, because her rudeness and pathological inability to play well with others isn’t aimed merely at press or Labour party but at her own colleagues, who thus, quite understandably, don’t want her as their leader. (For this, she blames them.) In some ways this is a shame. as I’d love to hear any explanation of the following diagram from her campaign materials, which seems to suggest she literally doesn’t know left from right. None, thus far, has been forthcoming.

That means the most likely victor must surely be Jenrick, who seems to have become the frontrunner mainly by aggressively briefing that he was, and whose main achievements in office were:

a) ordering that some murals on the wall of an asylum centre in Dover be painted over, so as to stop refugee kids from feeling tempted to travel thousands of miles in hellish conditions purely to look at a slightly off pictures of Disney characters; and

b) a reputation for personal integrity that resulted in the headline, in the London Economic, “All the times Robert Jenrick has faced corruption charges”.

Apparent gaffes, like Tuesday’s reports of his claim that special forces were being forced, by human rights law, to kill people, are unlikely to stop him: this seems like exactly the sort of madness the members go for. His actual personality, though, might: there’s polling evidence that there’s just something about him people don’t like1, and exposure to Jenrick the man rather than Jenrick the meme may be enough to arrest his momentum. There’s surely at least a chance that whoever makes it through to the members against him still wins by default.

All of which means the Tories are roughly where Labour were in 2010 – in denial about how bad the result is, convinced the unpopularity of the new government will be enough to turn things around in a single term. That, plus a leadership election ultimately decided by members – who are even less in touch with the real reasons for defeat than the Westminster contingent, if such things are possible – means there is absolutely no incentive to talk about the reality of why the party lost. The most likely result must surely be roughly the same as the result of the Miliband leadership, too.

“Most likely”, though, is not the same as “certain”. We live in volatile times. Nobody in December 2019 imagined Labour winning a landside at the following election: Labour faces an uphill battle to fix the British state, and while the mistakes of the last few weeks can be overstated, neither would you look at this government and say re-election was a certainty.

It must surely be possible, even if unlikely, that the pendulum swings again. There is just a chance that the scenes playing out at Tory conference right now turn out to matter after all.

More on this theme, outloud, on yesterday’s Oh God, What Now? with Andrew, Yasmeen Serhan and myself.

Live, and in colour!

Look at me, promoting something that isn’t that bloody book about borders for once. (Although the US/Canada version is out next week, and I’m meant to be reminding any North Americans that happen to be reading it that they should buy it? So please do.) Anyway: an exciting opportunity has arisen to watch me make an arse of myself with some real people.

At 3.30pm on Saturday 12 October – that’s a week on Saturday – I’ll be on the panel for the first ever Paper Cuts live show at the Clapham Grand. Miranda’s hosting, with Marcus Brigstocke, Coco Khan and (oh, christ) Gráinne Maguire completing the line-up. Miranda, Gráinne and I did a sort of trial run for supporters on Zoom last week and it was, despite our misgivings, one of the most fun things I’ve done in ages, so I’m hoping it’ll be good.

You can book your ticket here.

A rare theatre review: The Truth About Harry Beck

The Cubic Theatre, London Transport Museum.

The best moment in The Truth About Harry Beck, the Natural Theatre Company’s two-hander play about the man who designed the tube map, comes right in the middle (or, as Beck himself might say, somewhere around Oxford Circus). Simon Snashall’s fussy and obsessive draughtsman is trying to explain his concept for a new map (“It’s a diagram!”) to his adoring and tolerant wife, Nora (Ashley Christmas). To demonstrate that the key thing is not geography but clarity, he uses coloured ribbons to represent the different lines of the Underground, tied between furniture, hatstand and other bits of the set.

Suddenly, there it is – the familiar shape of the network, brought to life on the stage, and, with a little audience participation, labelled. A man in the front row is told that he is Kennington for the duration. It’s rather fun, and I was just thinking about how the lines Beck chose for his map are almost exactly the same colours you’ll find on a snooker table2, when we are told that London Transport has rejected his design. To sombre music, Nora and Harry – actually Henry; named Harry only because there already was a draughtsman named Henry in the office – sadly pack the ribbons away and briefly depart the stage. This, we are told, was the second of three rejections in the life of Harry Beck.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.