Where did it all go wrong?

This week: the collapse of the Tory party in review; and, in an unexpected twist, I have views about cricket. Also, an interactive train map. Cool.

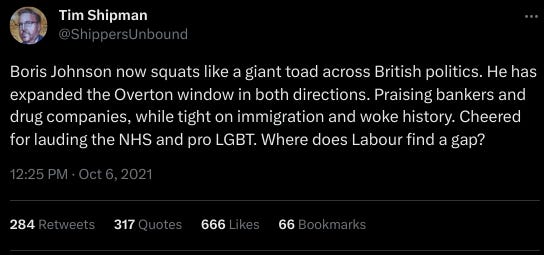

“Boris Johnson now squats like a giant toad across British politics,” begins a much-mocked tweet by the Sunday Times’ chief political commentator Tim Shipman. “He has expanded the Overton window in both directions.” And so it goes on.

To be fair to Shipman, I don’t think this intended to be entirely complimentary – no language I’m aware of includes the idiom “as sexy as a toad”, squatting or otherwise – but the reason the tweet caused such mirth was its timing. He wrote it on the 6th of October 2021; not quite three weeks later, on the 26th, the parliamentary standards committee ruled that Owen Patterson had breached rules on lobbying and should be suspended. Paterson maintained his innocence, Johnson attempted to rip up the entire parliamentary standards system to support him, and the resulting public outrage was noisy enough that it resulted in both a parliamentary rebellion and a very visible climbdown. And yet, by 10th December – the day, by my count, that Paterson’s 30 day suspension would have expired – Tory polling had plunged.

By then, of course, something else that happened to really hammer the stake in. Also that October, Pippa Crerar, then with the Daily Mirror, had received information that allowed her to stand up rumours that Downing Street had spent much of the pandemic partying. The resulting stories ran the following month, then reappeared, now accompanied by video evidence, on ITV News in the first week of December. A lot of things have happened since then – Liz Truss, remember her? Wild – but the key point for our purposes is that there is an exact moment the Tory dominance of British politics collapsed, and it was about 20 minutes after Tim Shipman sent his tweet.1 Labour hadn’t needed to find a gap: Boris Johnson blew one open for them.

So complete has this implosion been that it’s sometimes hard to recall that, for much of the time between the 2019 election and the autumn of 2021, Shipman would have had a point, about apparent Tory hegemony if not about the reasons for it. I have dim memories of despairing in writing about the party’s apparent ability to defy gravity, and to maintain a poll lead, not just at a time when a lot of things about the country were quite visibly getting worse, but after 11 years in office, at a point when surely boredom alone should surely have had the voters itching for a change.

There are all sorts of reasons why this didn’t happen and the party seemed to defy gravity, some of them obvious at the time and some only in retrospect. There was the coalition, which meant the first wave of dissatisfaction was absorbed entirely by the LibDems; a couple of well-timed changes of leader and direction; Covid, and the rally round the flag effect it produced; Corbyn, and the way the Labour party decided to dedicate the years between 2015 and 2020 almost entirely to fighting other bits of the Labour party.2 Looking back I sometimes wonder if the 2015 and 2019 elections were the outliers, and the freak 2017 result the “natural” trajectory, but even writing that down I’m worried the whole idea is meaningless so I’m going to move on.

The thing about gravity, though, is that you can’t defy it forever. So the other question raised by that tweet is why so little of the political class saw the inevitable coming.

One possibility is that we had all stopped believing that actions had consequences. Sure, things were going wrong: that was inescapable in the data on the economy and public services alike. But the Tories had done so well at protecting just enough of the electorate from the consequences, through differential spending cuts and booming house prices, that electorally none of it seemed to matter.

Another is that essentially nobody in this country has seen enough governments fall to understand how and why it happens. The sheer length of the last three governments means that, to have watched more than two changes of party in Downing Street in the course of your career, you’d need to be over 60 years old. We just don’t have enough of a data set to have an instinctive grasp on this stuff.

And then there’s the fact that the Tory approach to government – the reason it’s historically been such a successful party – is its ruthless ability to do whatever it needs to hang onto power. No idea, no policy, no leader is so sacrosanct they cannot be jettisoned if they stand in the way of a few more votes. In 2021 – even, in certain corners of the commentariat, now – there remained a belief that they’d find a way of changing direction and moving towards the voters again.

But just as the advantages of a pliant media become a problem once your popularity dips beneath a certain point, that same ruthless focus on the needs of your voters, which works so well when your base is broad, becomes counterproductive when it’s a small and shrinking minority of the electorate who are out of touch with the needs of the rest. Such as, for example, economically inactive and securely housed retirees. The result, in the words of John Oxley, is that the party…

…seems too impotent to address the failures that have led it here. It continues to be unable to achieve even the things it desires, opting for government by announcement rather than action. It would rather discuss the trivia which enrages its base than the pressing issues facing the country [and] would rather whinge about the things it sees holding it back… than utilise anything in its power to address it.

The reason the party is doing these pointless things, rather than solving any real problems, is simple: because it always seemed to work before. So when it didn’t, few in the political class, in the Tories or beyond, saw it coming. They were too busy instead marvelling at Boris Johnson squatting like a toad.

Every thought I had following an afternoon watching some cricket

“This is a newsletter brewing, isn’t it”, my friend and occasional co-author Tom Phillip said, somewhere around the 11th furious WhatsApp about a new format of cricket some friends had invited me to watch with them at the Oval on Sunday afternoon. I demurred – I mean, whatever the reason you people are all reading this, you don’t come for me to sport, do you – but I’ve always tried to keep the content of this thing as wide and unpredictable as possible, and another dozen or so furious messages about geography and Americanisation later I was forced to conclude that Tom was right. So, buckle up, it’s time for some games theory.

I’ve long suspected that I had the potential to like cricket. My dad used to play it. It was the one I was least bad at at school, in that I could, at least on occasion, get near the ball. It involves a lot of stats, and aimless radio commentary – essentially podcasts before podcasts existed – and equally aimless Guardian liveblogs. If I was ever going to develop an enthusiasm for any sport it was this one.

But as I watched the game, and watched the other people watching the game, awkwardly feeling more like a sociologist than a person who actually belonged there (“Oh, that chap behind me appears to be yelling obscenities at the man with the ball, how fascinating”), I realised that this was not the sport I’d expected. And worse, I had opinions about it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.