A reminder, should you need one, that if you want to subscribe to the full newsletter but can’t afford it, just hit reply and ask, and you can have it. I will say yes: I always do. (If you asked and I did not reply, it’s because I missed the email. Really. Someone did that this week and I felt horribly embarrassed and stopped what I was doing to immediately give him a comp.)

If you can afford it though…

This is the sort of thing that lies behind the paywall. Paying subscribers got it in March.

My book A History of the World in 47 Borders – currently available on Kindle or Kobo for just 99p, reading fans! – begins with a chapter on the unification of Lower and Upper Egypt around 3100BCE. This is one of the oldest political events in recorded history: I started the book there because it was the oldest political border I could find.

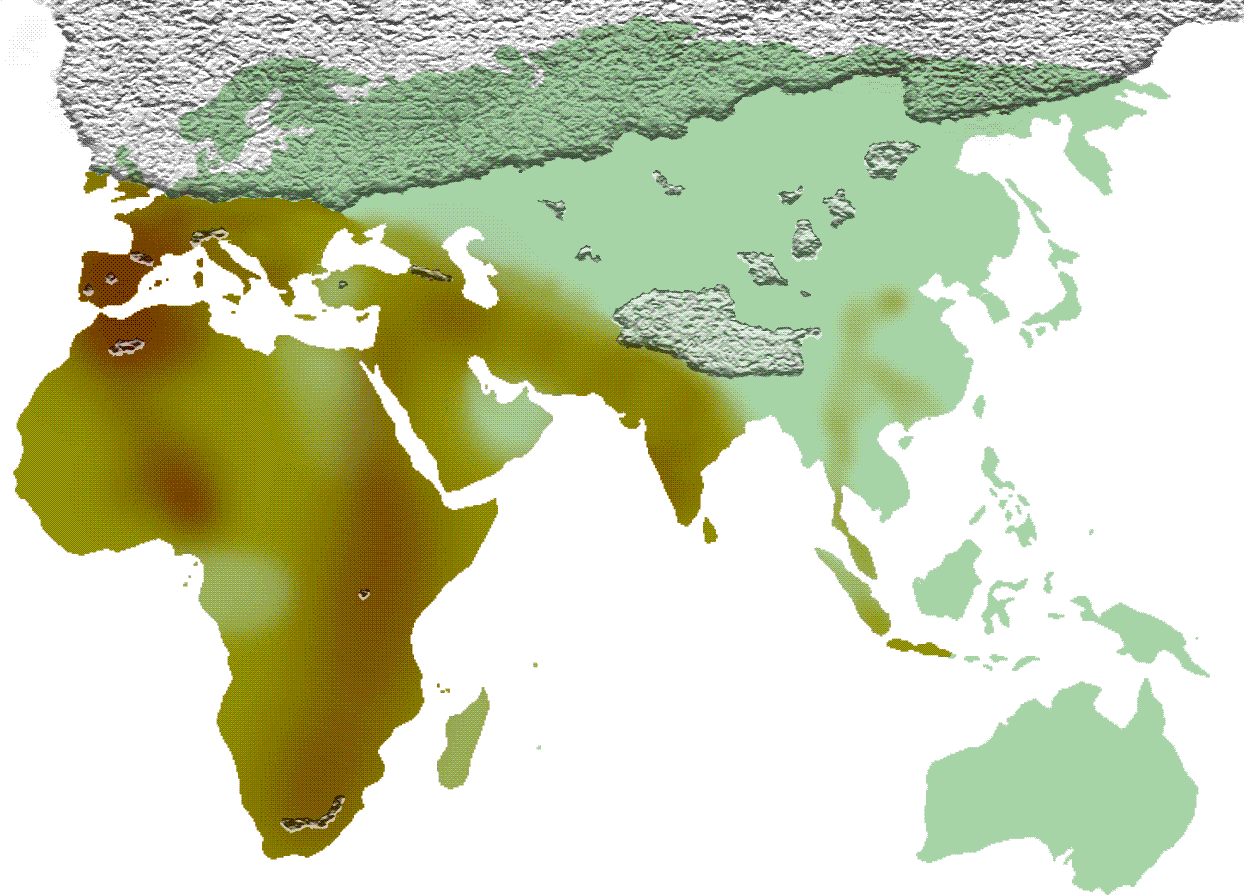

There are plenty of other ways of dividing up the world, however, and this is a map of a division that reaches right back to the stone age. One way you can tell that it’s old is because much of northern Eurasia is covered in ice.

Although the world the map shows is old, the line itself is a relatively recent discovery. Working in northern India around the time Richard Massingham was learning to cross the road, the entertainingly named American archaeologist Hallam L. Movius noticed something odd. In sites to the south, you would almost always find handaxes, the must-have tech of the paleolithic. In those to the north, however, you never would. Looking at other sites he worked out that you could divide the entire old world on this basis. The bit nearest to Africa had handaxes aplenty. East Asia, though, almost never did, its long-dead residents choosing instead to use less extensively worked tools known as “choppers”.

The Movius Line has been known of since 1948, and is, on the face of it, baffling. Early humans are believed to have originated in East Africa: why would they take their killer app from there as far as India, but then no further? Why, come to that, would it reach far off and chilly Britain, but not, say, central Asia?

Archaeologists have proposed a number of possible theories to explain all this. Perhaps the first humans to reach Asia may have done so before anyone had got around to inventing the handaxe, then had so little contact with those further west that the technology never spread. Or perhaps they did begin with handaxes but found, as they travelled further east, that the region lacked suitable stone, for either the axe itself or the implements necessary to shape it: within a few generations, they were thus as likely to produce them as you are to build your own smartphone. A third theory – this one’s my favourite – is that they found it easier to use tools made instead from bamboo, which were very useful but not likely to survive for thousands of years to be dug up by Americans with amusing names.

Another possibility is that Movius was simply overstating things. Since 2014, excavators claim to have found handaxes at a number of Chinese archaeological sites. Newspapers in China have gleefully reported this as a sign that the Movius hypothesis was simply wrong. Perhaps they’re right – but still, it’s funny what national pride can do isn’t it?

Extinct Animal of the Week: Teeny Tiny Horses

Paying subscribers got this in June.

One of the first things you notice about horses, should a bunch of them be running towards you on a grassy plain or through a plush west London street, possibly covered in blood, is that they’re quite large: around six feet (15 hands) tall at the shoulders, and perhaps half that again in length. This size is not incidental to their impact on human history: the reason they’ve been so useful in everything from carrying knights to pulling agricultural equipment to conquering the New World is because you can sit on top of one.

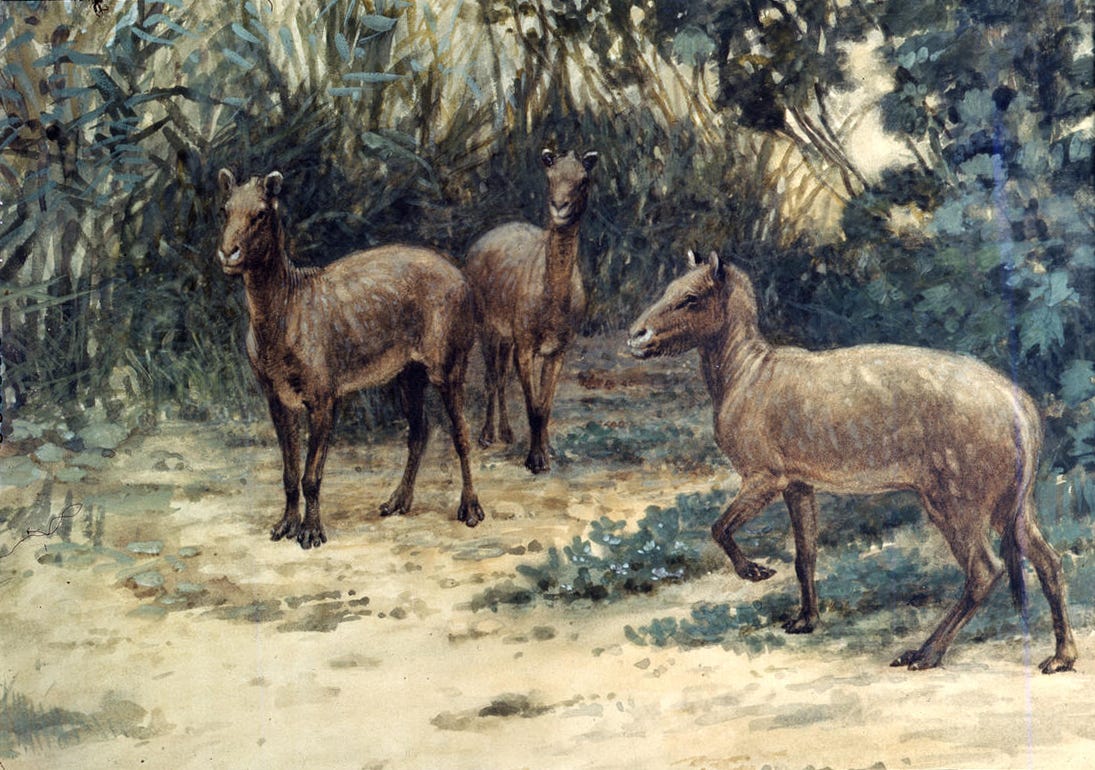

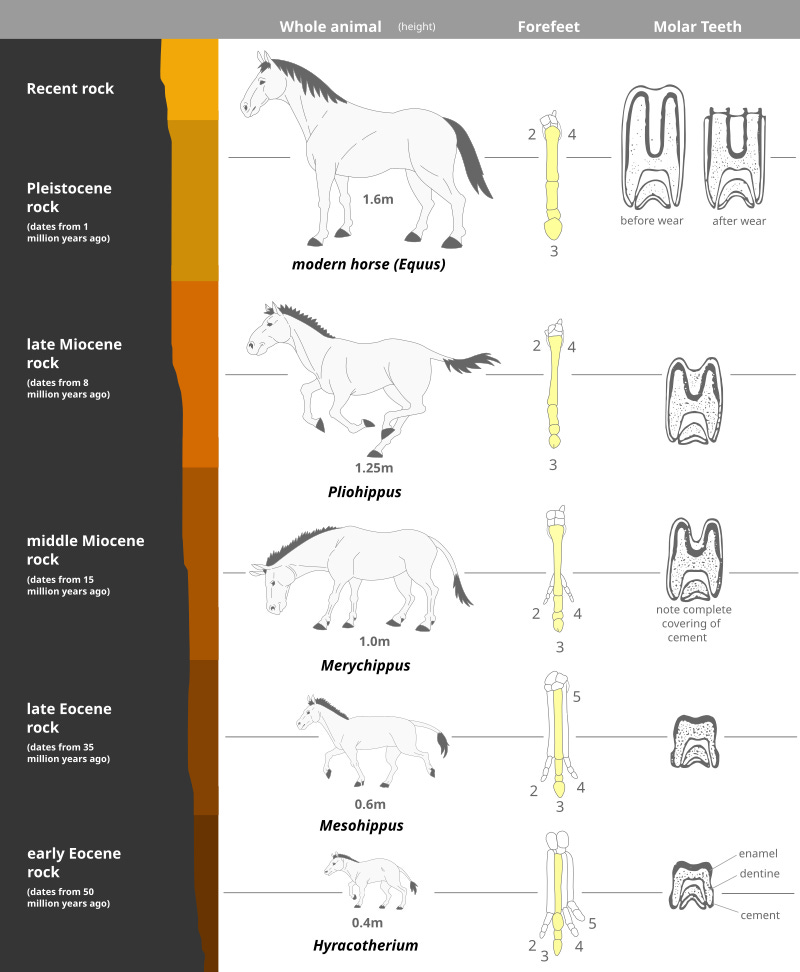

But horses were not always so imposing. In fact, the very first horses were quite a lot smaller. Somewhere, generally, between one and two feet high.

The creatures in question are generally known as eohippus – literally, “dawn horse”, in Greek – but should more properly be known as hyracotherium. The source of this confusion in nomenclature is that the latter name was coined first, by the (legendarily horrible) British palaeontologist and founder of the Natural History Museum Richard Owen. Later, the (presumably more personable) American palaeontologist Othniel Charles Marsh called another fossil eohippus, and later still people realised it was the same as Owen’s specimen. Marsh’s proposed name stuck – it is better, as was he – but the done thing is to use the first name, so really hyracotherium it should be.

Whatever we should call it, it was the first common ancestor of all modern horses, but not close cousins like the tapir and the rhinoceros.1 They lived between around 34 and 56 million years ago. They had four toes on their front feet, and three on their hind ones, each of which ended in a hoof. Their legs suggest they had evolved to run, presumably from predators; their teeth suggest they ate leaves. And they were absolutely tiny, the size of a small dog or large puppy.

Over time, though, their diet shifted from foliage to the newly widespread grasses: that meant an advantage to those with elongated skulls and larger, more durable teeth. At the same time, those who could outrun predators were more likely to survive to pass on their genes, which selected for longer legs and the gradual lifting of the smaller toes and the growth and strengthening of the longest. So over the eons, those puppy-sized eohippus got bigger, and their teeth got tougher.

Until modern times when you had a horse that was no longer the size of a puppy. It’s the size of a, well, horse.

One odd wrinkle is that much of this story seems to have taken place in what is now North America. On that side of the Atlantic, though, horses seem to have died out soon after the last ice age ended, around 10,000BCE. (We might also have hunted them to extinction.) That, suggests the historian Jared Diamond, meant a competitive advantage to the conquistadors who came from a culture where horses not only existed but had been domesticated – could be, among other things, weapons of war. Those native American tribes which roamed the great plains on horseback in the 18th and 19th centuries had only been horsemen for a couple of centuries: they learned to ride those who escaped from the European conquerors.

Incidentally, the smallest modern horse on record was roughly the size of an Eohippus. She lived from 200 to 2018, stood 43cm tall, and her name was Thumbelina. Here she is now. Awww.

If you want more about borders, then I know a good book. Makes an excellent gift for the human in your life! Alternatively:

Oh, and as promised, here’s Henry Scampi, with his mum, Olive:

For the avoidance of doubt, she’s the one on the right.

The one on the left is clearly a person.

I think. So far as one can tell there’s been a lot of debate about what evolved from what, which is probably natural when you’re trying to reconstruct tens of millions of years of family history from a handful of fossils, and if I’m absolutely honest I’m having some difficulty making sense of it.