So a thing I have learned this week is that bad things can happen, even if you refuse point blank to look at them?

On an unrelated matter, here’s another set of the potted bios of less remembered presidents I’ve written over the past few months. (You can read volume I, on Johns Quincy Adams and Tyler, here.) I was going to mix things up and send you something else from behind the paywall - but for some reason, this week it feels thematically appropriate to remind ourselves of the build up to, and failure of reconstruction after, the US Civil War. Next week’s archive post will be something very different.

As ever I would like it very much if you chose to become a paying subscriber. But I should also restate that you don’t have to, to read the newsletter: if you can’t justify the cost right now, for whatever reason, just hit reply and say you’d like a comp and you can have one, no questions asked.

If you would like to read more of me and can afford it/would like to help fund free newsletters for those who cannot, you can click here:

On a different matter: if you’re in London, why not come hear me read from and/or talk about the book at Backstory in Balham on Wednesday 20th November?

Right, let’s do this.

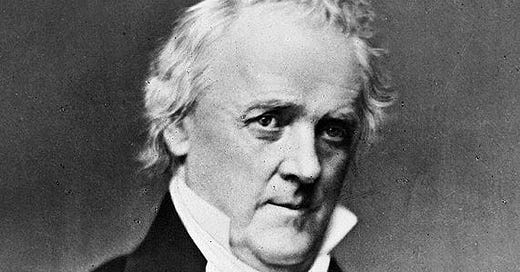

Half-forgotten US president of the week: James Buchanan

Lived: 1791-1868

15th president: 1857-1861

Perhaps I’m just projecting what I know here, but the official portrait of James Buchanan makes him look like a hapless sitcom character: there’s just something about that facial expression that makes me hear distant cries of, “Hennimore!” He served, his official White House biography begins, “immediately prior to the American Civil War, [and] remains the only President to be elected from Pennsylvania and to remain a lifelong bachelor”. Not only is this out of date – Joe Biden is from Pennsylvania – it feels a bit like beginning a description of Charles I by noting that, at 5’4, he’s believed to have been the shortest king of England. Sure, this is mildly diverting, but he broke his country. You’re burying the lede.

Buchanan was born to a large Ulster-Scottish family (eleven kids!) in the mountains of southern Pennsylvania in 1791, making him the last president to be born in the 18th century. He trained as a – sit down, this may come as a shock – lawyer, and had a pretty illustrious pre-presidential career: elected five times to House of Representatives, served as ambassador to Russia, then spent a decade in the Senate. After that he served as Secretary of State under James K. Polk, which, by my reckoning, means he shares blame for the war against Mexico (it wouldn’t be his last); then as ambassador to Britain under Franklin Pierce, his immediate predecessor and a president so forgotten I’ve not even found room for him in this column. Even though, of the presidents to that point, he was definitely the looker.

Being out of the country for the Pierce years turned out to be an advantage: it meant, according to that White House bio, that Buchanan hadn’t seemed to take sides in “bitter domestic controversies” that would soon take the nation to Civil War. He swept to the Democratic Party nomination in 1856, and thence to the presidency itself.

What were those bitter domestic controversies? If we wanted to be generous, we could note the tension caused by the shift in economic and political muscle, from agricultural south to increasingly industrial north. But we don’t want to be generous, because the biggest issues were whether it was okay to keep human beings as slaves, and who would get to decide that. (“States’ rights”, you’ll recall, often carries a silent “to be racist”.) Because these issues generally set south against north, Buchanan, a northerner from the southern-dominated Democratic party who’d kept his hands clean during the Pierce years, was assumed to be a fair dealer who could float above the fray.

That is not, it is fair to say, how things turned out.

Two issues in particular consumed US politics in the 1850s. One concerned the question of whether someone could remain another person’s property, even if they travelled to a bit of the US that didn’t recognise such things. (In theory, this had been addressed by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required the authorities in free states to return escaped slaves to their owners. In practice, many northerners hated this.) The other concerned the question of whether or not slavery should be legal in the western territories, then being settled by the US for the first time and gradually transformed into states.

Both of these issues came to a head almost immediately that James Buchanan arrived in Washington. In his inauguration, he dropped hints that a little bird had told him the Supreme Court was about to settle the territorial question, making it “happily, a matter of but little practical importance”. Two days later, the Court delivered the Dred Scott decision, ruling that Congress had no power to deprive people of their property rights.

That sounds innocuous enough, until you realise that the property in question was Dred Scott, an African-American who’d claimed he was no longer a slave on the grounds he’d been in the free territory of Wisconsin: the court had just ruled he was still a slave after all. More than that, by ruling that Congress had no power to deprive slaveholders of their property rights, the Court was also declaring the 1820 Missouri Compromise – which had accepted Missouri as a slave state in exchange for keeping all land north of a particular line of latitude slave-free – unconstitutional. Quite apart from being morally abhorrent, this destroyed the delicate power balance between north and south that had held sway for a generation. It handed a massive win to the pro-slavery south.

This must surely raise questions about the political instincts of any president who believed the ruling would settle things in and of itself, but that actually underplays things. Buchanan had in fact pressured the court to issue such a broad ruling precisely because he thought this would leave his presidency free to focus on other issues. He didn’t just welcome this outcome. He helped to create it.

No matter: it was early days for Buchanan’s presidency, there was plenty of time to reassert the balance of power. Another of the big issues in US politics in 1857 was “bleeding Kansas”: a series of violent outbursts between those settlers who wanted it admitted to the union as a slave state, and those “free soil” settlers who wanted it admitted as a free one. The Kansas Territory was north of the 36°30′ parallel, so under the recently struck down Missouri Compromise any new state there should have been slave free. The problem was, there were a lot more pro-slavery settlers than free soil ones. What to do?

After some deliberations, Buchanan decided to settle the matter by... supporting Kansas’ admission to the union as a slave state. He took the exact same side of the argument again. In an entirely unforeseeable development, this infuriated the north, and the Republicans, a party recently established specifically to oppose slavery in the western territories, won the most seats in the House of Representatives in the 1858 midterms. With a Democratic president and Senate, that meant deadlock.

Buchanan’s apparent instinct to take the south’s side reminds me of the BBC covering Brexit, or the New York Times Trump: he seemed so determined to show he was not biased towards his own side that he ended up biased towards the other. Though it seems an odd word to use about a guy who kept deciding that treating other human beings as property was basically fine, the issue seems to have been his naivety: he honestly believed that the key thing was process, that a political division could be settled through law. The problem was, in the words of a justly famous Tumblr post, that “everyone will not just”: just because the Supreme Court or the President had now ruled that slavery was fine, that didn’t mean the people who thought otherwise would just shut up and go away.

And they didn’t. Buchanan declined to run for a second term in the 1860 presidential election, leaving the Democrats to find another candidate. In the event they found two: Stephen A. Douglas, representing the existing Democratic party in the north; and John C. Breckinridge, representing the newly independent Southern Democratic party in the south. Unsurprisingly, given this split, both lost: Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected without a single vote from south of Virginia, and a bunch of southern states responded to this victory by seceding.

James Buchanan had presided over the break up of the United States.

He wasn’t wild about this, in his defence, but he visibly had no clue what to do, arguing both that states couldn’t secede and that they couldn’t be prevented, sending troops to prevent secession but then spending the last two months of his presidency on a “policy of inactivity”. Two months after he left office, the Civil War began; he was dead before the decade was out. In the century and a half since, fierce debate has ranged over whether Buchanan was the worst president, or merely one of the worst.

Three other things before we leave this subject behind. Buchanan, like Pierce before him, was often described as a “doughface”: a delightful mid-19th century insult for a northerner who kept taking the south’s side. Apparently it implied softness and pliability, a willingness to be led by those of stronger temperaments.

Secondly, as I discovered in a wasted hour of my youth when I decided to list US presidents like kings, James is the single most common forename among US presidents: James Bucnahan (“James IV”) is one of six men named James to hold the job. I find this interesting, even if you don’t.1

Lastly, because Buchanan never married, the role of “First Lady” fell not to his wife, but to his niece Harriet Lane, who’d been orphaned aged 11 and thus became his ward. She, unlike her favourite uncle, apparently did a sterling job.

Perhaps it wasn’t a sitcom character I could see in Buchanan. Perhaps it was Dickens one.

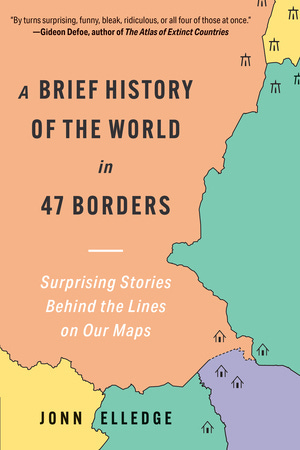

Half-forgotten president of the week: Andrew Johnson

Lived: 1808-1875

17th president: 1865-1869

It’s tempting to feel sorry for Andrew Johnson. He isn’t the most famous or successful President Johnson. (Hey, hey, LBJ!) He isn’t the most famous or successful president named Andrew, either. (The other, Andrew Jackson, came first, has an annoyingly similar name, and gets to be lionised for creating the Democratic Party, even though one of his main achievements in office was an enormous act of ethnic cleansing.) When I fed his name into my phone’s search function, it suggested two footballers, a golfer and a funeral parlour in Plumstead, before considering I might be looking for the president: hardly anyone even remembers that this guy existed.

On the other hand though, he never bothered to win an election, threw former slaves under the bus during Reconstruction and came extraordinarily close to being impeached, all of which feels like an extremely strong case to think f*ck that guy.

When last we spoke, Abraham Lincoln had just won the 1860 presidential election for the new anti-slavery Republican party, without even being on the ballot in most of the south, leading a bunch of southern states to break away. The result was the US Civil War – you’ve probably heard of that2 – which was just approaching its conclusion at the time what was left of the United States held the 1864 presidential election. Lincoln won a second term in a landslide, beating his Democratic opponent George B McClellan 55% to 45%, and carrying 22 states and 212 electoral college votes compared to just three and 21 for McClellan. (Lincoln also, incredibly, won the recently recaptured confederate states of Louisiana and Tennessee, but their votes weren’t counted.) All looked set for four more glorious years.

But then, just six weeks after being inaugurated, President Lincoln decided to spend an evening at Ford’s Theatre, and that was the end of that.3 So: as had been established by John Tyler following the death of William Henry Harrison a quarter of a century earlier, the vice president took over.

Here’s the thing, though. The vice president was not the guy who’d been serving alongside Lincoln since 1860 (Hannibal Hamlin, a former Senator and – innovative, this – lawyer). He wasn’t even a Republican. Andrew Johnson was both a southerner and a Democrat. And at the time he became president, he had been vice president all of 42 days.

Johnson had not, to be fair, grown up in one of those southern families whose entire living came from the hard work of the other human beings kept in bondage slavery: no, he had decided to buy his own slaves in his 30s as a mark of his success in life. Nor, unusually, was he a lawyer: indeed, he’d had no formal schooling whatsoever. Born in Raleigh, North Carolina, he’d grown up in poverty, been apprenticed as a tailor, run away and settled in Greeneville, Tennessee, where he’d started his own tailoring business.

He embarked upon a political career in the 1840s, and pursued what sounds a lot like populism, even if that term is an anachronism. As variously a Congressman, governor of Tennessee, and a Senator, he was, according to his White House biography, a passionate speaker, “championing the common man and vilifying the plantation aristocracy”: one of his big causes was the Homestead Bill, which would have provided free farmland for poor men. (This might go some way to explain why he’d joined the party of Andrew Jackson, a president who had freed up rather a lot of inconveniently occupied land.)

So how had this southern Democrat ended up as vice president to a northern Republican? Because, when Tennessee seceded, Johnson didn’t: he was the only southerner to remain in the Senate, making him a hero in the US but a traitor to many in the Confederacy. In 1862, after the north had reconquered Tennessee, Lincoln named him its military governor.

Two years later he went even further. For the 1864 election, the Republicans temporarily merged with War Democrats and other supporters of the northern cause into something called the National Union Party. In an attempt to increase his appeal to southern unionists and bind the nation together, Lincoln had kicked Hamlin off the ticket and replaced him with a Democrat from Tennessee – a border state pulled back into the union so recently that its votes wouldn’t even count.

This probably seemed like a pretty clever move. But none of the northern Republicans congratulating themselves on their bipartisanship, surely, expected the southern Democrat to end up with the big job.

And once the war was won, Johnson had his own ideas about Reconstruction, which prioritised reconciliation between the warring elites over any moral principles that the war might have been fought over. He directed the newly readmitted southern states to elect new governments, and automatically pardoned most southerners who’d take an oath of allegiance. (“Leaders and men of wealth”, that White House bio adds, were required to “obtain special Presidential pardons”, which sounds a lot like “asking nicely”.) At the same time, while slavery had now been abolished, Johnson did little to stop the recently readmitted states from introducing “black codes”, to make sure freedmen remained, at best, second class citizens.

This did not go down well with Republicans in Congress, which had not been in session for the first few months of his presidency. The Radicals – whose radicalism, it’s worth noting, lay mainly in their belief that black people should have the same rights as white people – attempted to block former confederates from taking their seats, and to pass measures protecting the rights of former slaves. Johnson vetoed them; Congress overrode his veto. After that, Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment, which specified that no state should “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”, essentially protecting the rights of former slaves. Johnson opposed that too. (It passed anyway, albeit without support of any former confederate states except Tennessee.)

And so it went on. Relations became so bad that Congress eventually passed a law to restrict the president’s ability to pick his own Cabinet; when he ignored it, by firing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Johnson became the first president to be impeached by the House of Representatives. He was acquitted in the Senate, by a single vote.

Oddly enough the Democrats didn’t renominate him in 1868. No matter: the Republican candidate, the former general of the army Ulysses S. Grant, won anyway. The party of Jackson and Johnson would lose every presidential election bar four (two Grover Cleveland, two Woodrow Wilson) for the next six and a half decades all the same.

In some ways, Johnson’s sin was the exact same thing he’d impressed everyone with in the first place: his belief that national unity should matter more than these silly arguments about slavery. As a result, the best the normally hagiographic White House biographers can come up with is “an old-fashioned southern Jacksonian Democrat of pronounced states’ rights views”. (Yes, we all know by now what that means.) Most authorities are rather less euphemistic. “Historians view Andrew Johnson as the worst possible person to have served as President at the end of the American Civil War,” writes Elizabeth R. Varon, professor of history at the University of Virginia. “He is viewed to have been a rigid, dictatorial racist who was unable to compromise or to accept a political reality at odds with his own ideas.”

Johnson freed his slaves in 1863, and seems to have been a decent enough master for them to remain in his household by choice as paid employees. But he still chose to acquire and keep at least 10 of them; and he spent his presidency trying to deprive them of rights. “In the end,” Varon concludes, “Johnson did more to extend the period of national strife than he did to heal the wounds of war.” Some people deserve to be forgotten.

If you want to read more stuff like this/support the kind of nerd who writes it, then as ever paying subscribers get more things, much earlier!

If you can’t afford to pay then just hit reply and you can have a freebie. Really, it’s not a trick; if you already did this and I didn’t reply it’s because I missed the email, just kick me again.

But if you can, here’s a convenient button to help with that:

And if you enjoyed all that, you might also enjoy my book which also, as it happens, makes a brilliant Christmas present:

Also now available in North America!

There have also been four Johns, four Williams, and three Georges, which enjoyably makes George W. Bush “George III”, like the guy the War of Independence was against. Perhaps the most unexpected repeated name is Franklin, of whom there have been two: Pierce and Roosevelt.

I sometimes wonder though if our relative ignorance of it on this side of the Atlantic is one of those things that made the First World War so horrifying. There’d been no serious conflict in Europe since the Napoleonic Wars, a century earlier; perhaps if they’d seen the US Civil War, they’d have had more of a sense of what was coming? That said, I’m not entirely sure this isn’t nonsense, which is why it’s in a footnote.

The story of Lincoln’s assassination is pretty incredible. His assassin John Wilkes Booth was not only a confederate sympathiser but a genuinely famous actor – it’s like Joe Biden getting shot by, I dunno, Channing Tatum. What’s more, the plot really was the result of the sort of conspiracy that there would be absolutely no evidence of when Lee Harvey Oswald killed JFK 98 years later. But I’m not writing about that here, and anyway you can read about it in one of Tom Phillips’ chapters of our book Conspiracy: A History of B*llocks Theories, and How Not To Fall For Them.