Before we get started, it’s time for this year’s big pledge drive/attempt to grow, or at least arrest the inexorable decline of, this thing… Sign up for an annual subscription to this this newsletter, and I will give you 5% off *and* throw in a free copy of my book A History of the World in 47 Borders: The Stories Behind the Lines on Our Maps when it comes out in paperback on 27 March.

Do so, and every Wednesday, I will send you a selection of divertingly nerdy things like this, originally published November…

A few months ago, a long-time reader and social media mutual told me that they were disappointed to see me effectively dead-naming an entire country by referring to “Turkey” throughout my book. I responded by arguing that this was the standard English name, that using “Türkiye” would be just as weird as referring to Germany as Deutschland or going round pointedly calling it Fronce, and was feeling all pleased with myself when someone else popped up to point out that Türkiye had officially changed its name in 2022, and it’s just that I hadn’t noticed.

Oh well. It’s all content isn’t it? Let’s talk about some countries that changed their name.

Myanmar

The government of the country historically known as Burma announced it would henceforth be known as Myanmar back in 1989. The former is a British colonial name, imposed by outsiders; the latter the country’s name for itself. Simple, right?

Well, no, there are a couple of complicating factors. Firstly, it turns out that Myanmar and Burma are, unexpectedly, the same name: the Burmese language has very different vocabulary for different registers, and Myanmar is the formal, written version for the more colloquial Burma. Inside the country, the rebrand changed nothing.

Secondly, that rebrand came a year after the military government attempted to suppress a pro-democracy uprising, making itself a pariah: that raises questions about whether it was quite as into freedom and self expression as it claimed, or whether the name change was a distraction. As a result, much of the world kept calling the country Burma for years as a way of supporting the opposition.

Czechia

So you probably know that the Czech Republic – a region divided into Bohemia, Moravia, and (parts of) Silesia, but historically referred to simply as “Bohemia” because that was the name on the crown – has been attempting to rebrand itself for a while. The Czech government, sick of all this “Czech Republic” nonsense which most of its peers don’t have to put up with, announced in 2016 that it would henceforth be known in English as “Czechia”.

What you might not realise, though, is that the Czech government was using the shortened form as far back as 1993, and some bits of civil society have been pushing the new name for roughly as long. It wasn’t so much a rebrand as a reminder we’d all been rudely using the wrong name for decades, like we’ve been calling someone Mike when he’s actually named Matt. Oh well. It hasn’t entirely taken, but at least people are using both now.

Cabo Verde

Tiny country consisting of 10 islands off the coast of West Africa. Its name – “green cape”, in Portuguese – actually refers to a bit of the Senegalese coast, a few hundred miles of Atlantic Ocean away, and generally known by the French Cap-Vert. The islands somehow ended up known, in English, as Cape Verde.

Hearing your name bastardised in the language of a country that didn’t even colonise you, though, is apparently quite irritating. So in 2013 the republic’s government informed the UN they should use Cabo Verde, as that’s the correct name in the local language of Portuguese. Why they are not also irritated at being referred to by the name of a geographical feature that they definitely aren’t, and are indeed several hundred miles distant from, is outside the scope of this newsletter.

The Democratic Republic of Congo

The second longest river in Africa, beaten only by the Nile, was once known as the Zaire, a Portuguese adaptation of a Kinongo word nzere (“river”). Over time, though, it came to be known as the Congo, after a people and kingdom based on its southern banks.1

When the Belgian Congo, a colony so well-run that it inspired Joseph Conrad to write Heart of Darkness, won its independence in 1960, it called itself the Republic of the Congo. This was from some perspectives difficult, because there already was a Republic of the Congo, just across the river, in the process of gaining its independence from France.2 So in 1964, the former added the word “Democratic” to its name, to help clarify things. In 1965, there was a military coup, and the new president Joseph-Désiré Mobutu got increasingly into authenticity, renaming first himself, to Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga, and then, in 1971, renaming his country Zaire.3

After Mobutu was finally forced into exile by rebel forces in 1997, the country reverted to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Even though it isn’t.

North Macedonia

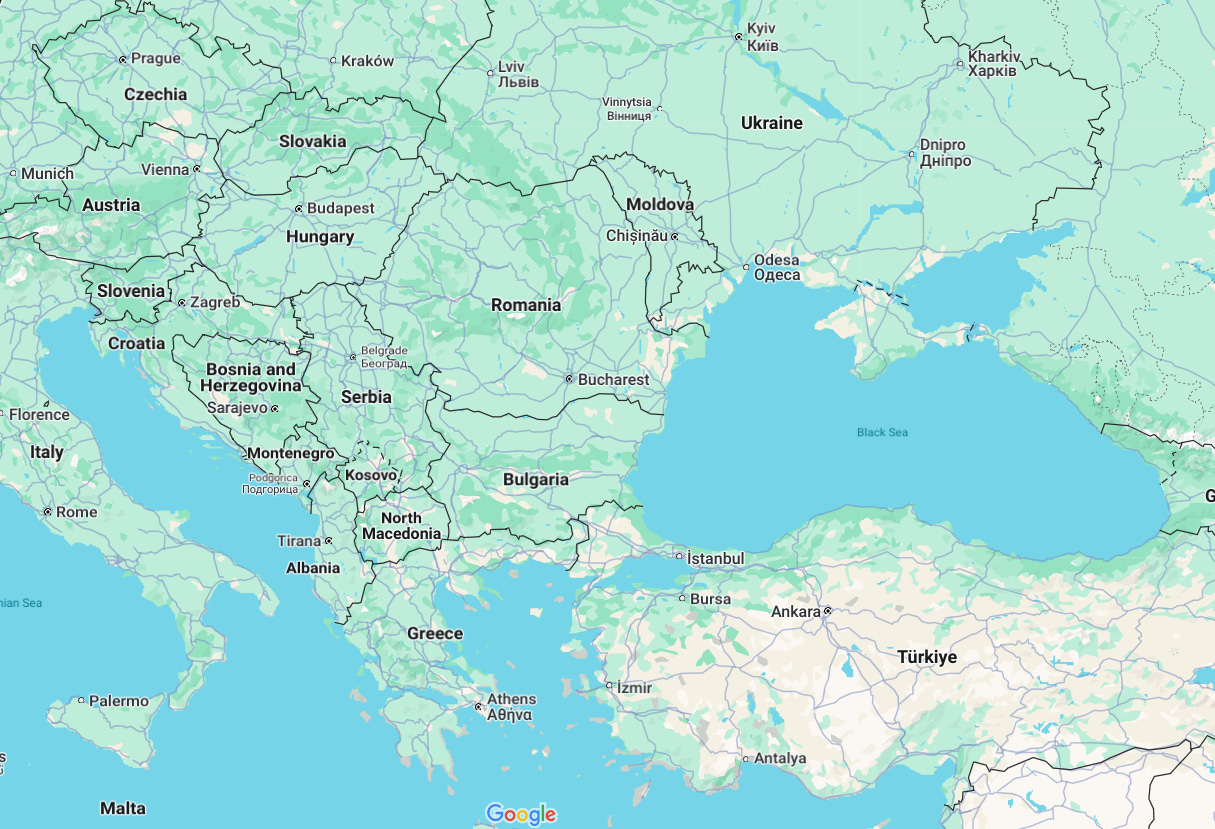

In the 4th century BCE, Alexander of Macedonia conquered the known world. Apparently that’s long enough ago for everyone to think this naked act of imperial conquest cool, so today there are two places that want the name Macedonia. One is the Macedonian region of northern Greece. The other is the independent republic directly to its north.

The former’s case is, essentially, this is where Alexander the Great’s capital was. The latter depends on its use by assorted Macedonian nationalist movements, first in the Ottoman Empire in the late 19th century (which didn’t like nationalist upstarts in general), then in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the early 20th (which strongly felt everyone should be Serbian). After Yugoslavia became Communist in 1945, the name Macedonia was slapped on one of its six constituent countries, which carried it into independence.

All this rather upset the Greeks, because Alexander was theirs, and because they were a little worried that it implied designs on their own Greek Macedonia. So when the newly independent country was admitted to the UN in 1993, it was under the provisional name of “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” (“FYR Macedonia” or “FYROM”). A quarter of a century of legal back and forth – and Greek veto of its neighbour’s attempts to join NATO or the EU – later, Macedonia finally agreed to rebrand itself North Macedonia at the Prespa Agreement of 2018. Everyone in the country ignores the “north” bit anyway.

Eswatini

The Prespa Agreement made North Macedonia the second country to rename itself in less than two months. The absolute monarch of the tiny landlocked southern African kingdom of Swaziland – it’s a little bigger than Yorkshire, with about a fifth of the population – had grown sick of everyone confusing his kingdom with Switzerland.

“Eswatini” also means “land of the Swazis”, but in the Swazis’ own language (an endonym, rather than an exonym). So the Swazis simply switched to that. And why not? It suits them.

Zambia and Zimbabwe

In the colonial era, the lands that today make up Zambia and Zimbabwe were known as Northern and Southern Rhodesia, after Cecil Rhodes, the managing director of the British South Africa Company, whose employees settled the region at the turn of the 20th century. This obviously felt a bit off to those who already lived there, so on independence in 1964 the northern bit renamed itself “Zambia”, after the Zambezi River.

That left Ian Smith, the horrible white supremacist Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, in sole possession of the name “Rhodesia”, so he dropped the word “southern” from his bit. Then, fearing that the British government of Harold Wilson might demand majority rule before granting independence, Smith unilaterally declared it anyway, leading to 15 years of white rule, sanctions, guerrilla warfare and pariah status.

Following Smith’s fall, the country rebranded itself Zimbabwe, after the medieval city of Great Zimbabwe. After that I’m sure everything was probably fine.

(An extra vaguely related fact I’ve never stopped being slightly surprised by: in the play on which classic BBC drama Our Friends in the North was based, the “north” referred not to “Newcastle” but to “Zimbabwe”. It was about gun running. Huh.)

Türkiye

Okay, let’s do this. The foreign minister of the Republic of Turkey submitted a request to the secretary-general of the UN to officially rebrand the country as Türkiye in 2022. It’s not just an alternative spelling, helpfully containing a vowel that doesn’t exist in English: it’s a different pronunciation, somewhere closer to Turkia or Turkey-eh.

The reasoning behind the change, and you can’t really fault the Turkish government for this, is “It’s slightly embarrassing having the same name as a huge ungainly bird”, especially since that bird was never native to Türkiye in the first place. It’s actually from North America: they became known as “turkey cocks” in English because they were sold by merchants trading with Constantinople; other European languages instead place their origins in India or, unexpectedly, Peru.

Anyway, a quick flick through the papers suggests that many publications remain just as ignorant as I was about the rebrand. On the other hand, though, Google Maps uses the correct name, so perhaps it will embed over time. Or perhaps it’ll be Czechia all over again.

Timor-Leste

East Timor, which occupies the eastern half of the island of that name, was a Portuguese colony until 1975. It declared independence on 28 November 1975; was invaded nine days later by its much bigger neighbour, Indonesia, which held the western half of the island; then annexed just over seven months after that. Its independence struggle finally came to fruition in 2002, when it became the first new sovereign state of the 21st century under its new name of Timor-Leste.

Not only is that the Portuguese for East Timor. But Timor itself literally means “east” – it’s a variant of the Malay Timur, a reference to the fact it’s the easternmost of the Lesser Sunda islands. That means that, in the period of Indonesian dominance, the province was known as Timor-Timur.

I realised halfway through writing this that this was not technically an example of the country which has changed its name. But this fact was simply too delightful not to share.

Actually that seems to be a truncation of nzadi o nzere (“river swallowing rivers”).

For a while they were known as Congo-Léopoldville and Congo-Brazzaville, respectively, after their capitals. Since both capitals were named for European colonisers, albeit one substantially more implicated in atrocities than the other, this does not feel like a brilliant solution either.

He also named Léopoldville “Kinshasa” – and thus Congo-Léopoldville as “Congo-Kinshasa” – which, given how much damage Leopold II had done to the place, frankly seems more than fair enough.