The man who spread conspiracy theories about his own death, and other stories

A brief history of conspiracy theories (with jokes).

A History of the World in 47 Borders just came out in paperback. If you’ve been foolish enough not to take up my special offer of 5% off this newsletter and a free copy, then, well, here’s your chance:

Because I’m perverse, though, this dip into the archive is something I wrote to promote a different book entirely. Paying subscribers got this months ago, the lucky lucky people.

Last June the Fortean Society asked me to give the “ease everyone into the day” session at a conference, by (I paraphrase, but not by much) summarising the entire history of conspiracy theories, with jokes. I rapidly decided that was a bit much – partly because it had taken Tom Phillips and I an entire book to do that and I only had half an hour, partly because Tom wrote all the clever bits, but mostly because it came right in the middle of the UK’s general election campaign and I was absolutely knackered.

What I came up with instead was a sort of listicle, in which I identified some of the key dates in the history of conspiracism, explained why they mattered, and then summarised some of the themes that emerged. What follows was inspired by that talk.1

October, 19CE

Germanicus Caesar was a very successful Roman general, and a plausible heir to the imperial throne then occupied by his uncle Tiberius. If you’ve ever seen I, Claudius, you may remember him as Derek Jacobi’s hunky older brother.

You will also remember, if you’ve ever seen that fine bit of BBC drama, or indeed read the Robert Graves novels it was based on, that plausible heirs to the imperial throne had a habit of dying suspiciously often and suspiciously young. And so it proved with Germanicus, who became horribly ill while on campaign in Syria and died, aged just 33. It’s possible this was natural causes; it’s equally possible it was not. We’re never going to know.

The key thing for our purposes, though, is that it took him a month to die. That gave him time to accuse both the governor of Syria and his own uncle of poisoning him. You may or may not consider this paranoia – he genuinely was dying, and being the imperial heir was not a safe thing to be – but it does make Germanicus the source of the oldest conspiracy theory we could find. More than that: it gives him the rare honour of being one of the few people ever to spread conspiracy theories about his own death.

1776

You may notice we’ve jumped forward by quite a long way there. I could have stopped earlier, to talk about the anti-semitic blood libel, which has its origins in a specific conspiracy theory which sprang from Norwich in 1144; or possibly the Popish Plot of 1678, in which a man named Titus Oates went around claiming Catholics were trying to murder Charles II and take over the country, and which is notable mainly because one of the main people going around saying this was bullshit was, er, Charles II.

But one of the theories we put forward in the book was that, while the evolved impulses that drive this stuff have been with us forever, for conspiracism to become a serious political force you sort of need, well, politics. “There’s something they’re not telling you” is not a meaningful statement in a world dominated by church and crown, where there are loads of things the ruling class aren’t telling you and nobody would expect otherwise. To really bloom, conspiracism requires the Enlightenment.

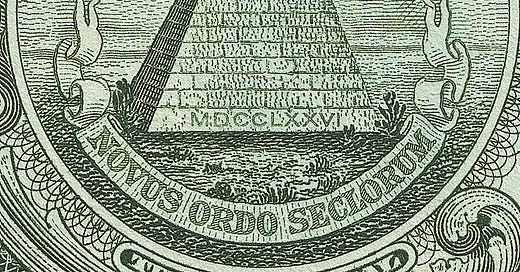

The reason I’ve chosen 1776, though, is probably not the one you think: the foundation of the United States is a cute coincidence. The reason we’re stopping here is instead that this was the year when an Ingolstadt-based philosopher named Adam Weishaupt founded a secret society to push radical and sinister ideas like republicanism, secularism, liberalism and (most shocking of all, this) gender equality.

The Union of Perfectibilists was a little more than a Bavarian book group: it struggled to attract members, and when it did immediately fell to infighting because Weishaupt didn’t like them. The Bavarian authorities eventually tried to ban the thing, and it all collapsed in a sex scandal involving Weishaupt’s attempt to procure an abortion for his sister-in-law. The whole affair lasted less than 10 years.

The only reason it matters at all is because it wasn’t always known as the Union of Perfectibilists. You know it as the Illuminati. Yes, they existed; yes, they wanted to overthrow German society. No, they didn’t manage it, and no, they don’t exist any more.

So why have we all heard of them? Why do they get the blame for everything?

Short version: because a couple of years after the Illuminati collapsed, the French Revolution happened. To the conservative, royalist or anti-enlightenment forces horrified by events in Paris, it couldn’t simply be that yawning inequalities of wealth, power, or tax burden had turned out to be unsustainable: someone must have done it.

The Illuminati weren’t the only ones in the firing line: Freemasons, philosophers, and Voltaire all got the blame too, which was particularly clever of the latter, who’d been dead 11 years. But a guy who’d basically been rejected for membership of the Illuminati started telling people it was them, and books began appearing blaming them explicitly, and that in turn set off a wave of panic in the newly formed United States.

Which led, nearly two and a half centuries later, to Infowars telling everyone that Katy Perry was a member of the Illuminati because the video for Dark Horse had some eyes in it. Stands to reason.

1832

Cholera, recently arrived from Asia, went epidemic across Europe for the first time, killing vastly more poor people than rich ones in the process. The result, in Britain, was riots; in France, a revolution. Another one. The one from Les Mis.

But because no one understood germ theory yet, no one knew where the disease was coming from, and so conspiracy theories started to spread. Some of them involved the government deliberately spreading the virus to wipe out the poor; others concerned the medical response, as some became convinced that doctors were killing people just to get hold of their corpses. (Burke and Hare, at this time, were still fresh in the memory.)

It’d be another 22 years before John Snow proved that cholera comes from dirty water. It’d be a whole lot longer than that before pandemics stop being a cause of conspiracy theories.

1947

A big year, when two of the founding events in ufology happened almost back to back. On 24 June, a US Air Force pilot by the name of Kenneth Arnold saw nine disc shaped objects in the sky, not far from Seattle, and made the mistake of telling the press. Arnold was a sensible sort, so the reports were written up pretty straight. Nonetheless, all this had two immediate results:

1) the popularisation of the term “flying saucer”; and

2) Arnold wishing he’d kept his mouth shut because it pretty much ruined his life. “I’m wondering what my wife back in Idaho thinks,” runs one quote.

Just two weeks later, some mysterious wreckage crashed to the ground not far from Roswell, New Mexico, and a junior air force officer did exactly what you’re not supposed to do when involved in a conspiracy to cover up the existence of alien life: he issued a press release. (It even referred to a “flying disc”, suggesting he’d been reading the same newspapers as everyone else that week.) The next day, a more senior officer clarified that it was actually the remnants of a weather balloon. This served mainly to make it look like the US government had announced the existence of aliens, and then tried to walk it back. Great work.

It’s worth noting that this was absolutely not the earliest example of people seeing weird stuff in the sky. In earlier centuries, though, such things were generally credited to god or gods. Nobody started assuming they were alien in origin until, firstly, humanity had learned to fly (so it becomes possible to conceive of intelligent life up there), and secondly the Manhattan Project had invented the bomb (thus making it a potential source of Armageddon).

As it happened, though, nobody much cared about all this in 1947: ufology only really took off in the 1970s, when a rush of books appeared alleging a cover up. The reason for that may be that those involved were now retired, and could thus Speak Their Truth/Seek Their Payday. But it may also be that, in the intervening decades, faith in the US government had collapsed, because of a date that will live in infamy.

Apart from anything else, it delayed the first ever episode of Doctor Who.

22 November 1963

You may have some sense that there’s something a bit iffy about the assassination of JFK. You probably don’t imagine there was a superconspiracy involving the USSR, Cuba, FBI, CIA, LBJ and so forth… but you may, nonetheless, have questions. About the magic bullet; the route of the motorcade; the need for a second shooter.

If so, you wouldn’t be unusual. Polls have frequently found that a majority of Americans believe that Lee Harvey Oswald didn’t act alone. A majority of Americans, in other words, believe in the archetypal example of a conspiracy theory.

The thing is, though: Oswald almost certainly did act alone. He was a paranoid man, who’d defected to the Soviets and back, tried to assassinate military officers and left evidence suggesting he was planning to assassinate the president. There’s no need for a “magic bullet”, either: the seats in the car were not arranged in the manner you imagine or Oliver Stone suggested. The number of necessary bullets matches the number of known shots. There is neither evidence of, nor need for, a second shooter, let alone a plot related to US involvement in Vietnam or anything else.

So why have so many people – clever people, like Bertrand Russell! – dedicated so much energy to looking for one? One reason is “proportionality bias”: the very human need to assume that an event which caused such trauma must have a proportionally large cause. One guy with a gun just doesn’t feel big enough, just as a car crash doesn’t feel big enough to have killed Princess Diana.

The other reason, though, is everything that happened later. More assassinations: MLK; RFK. The Warren Commission, tasked with investigating the assassination, which probably did cover some stuff up (nothing to do with assassination, but instead to do with US foreign policy). Escalation in Vietnam. Waves of urban riots.

By the time the Watergate scandal broke in 1974, the US had become a much more divided, and much less deferential society. The JFK assassination is pretty much the inciting incident for that process of lost trust. That, too, may be a reason people just assume there must be more to it than one guy with a gun.

1966

Paul McCartney dies in a car crash, and is replaced by William Shears Campbell – a man who not only looks like him, but sings like him and turns out to be one of world’s most innovative songwriters. The surviving Beatles, wracked with guilt, leave a series of clues that McCartney is dead. Paul walking barefoot on the cover of Abbey Road. Paul, wearing a black armband with the letters OPD – “officially pronounced dead”2 – on the cover of Sgt Pepper. On Magical Mystery Tour, one of the Beatles is dressed as a black walrus, the Scandinavian symbol of death.3

This is all, of course, nonsense. I don’t just mean because it’s all terribly unlikely, but because we literally know who started it: a couple of student newspapers, in Michigan and Iowa; a radio phone-in, discussing the “clues”. Even though no one took it very seriously, the rumours spread for much of 1969 until the band was issuing press releases and a team from Life magazine tracked McCartney down to his farm in Scotland, and got a bucket of water over themselves for their trouble. (They were so delighted to get the “Paul not dead” exclusive that they missed the rather more world-shaking “Beatles no longer a band” one. Honestly, he told them, and they buried it.)

The point of this story is that things begun as jokes do not necessarily remain so. In the 2010s, a long-standing joke in the Brazilian bit of the internet escaped containment, and a bunch of Avril Lavigne fans became convinced she’d killed herself and been replaced by a body double. It didn’t matter that it had begun on a blog whose subtitle translated as, “This blog was created to show how conspiracy theories can look true”: vast swathes of the internet henceforth dedicated themselves to uncovering the clues.

1991

Remember crop circles? Which were often blamed on aliens? And were talked about in the same breath as the conspiracies to suppress evidence thereof?

Well, it turned out that they were the result of a conspiracy, but one which had absolutely nothing to do with aliens. It was a conspiracy instead between a couple of Wiltshire blokes in a pub: 1991 was the year they came forward, admitted they’d made 200 of the things since the late 1970s, and then made a new one in front of the press to prove it. A “cerealogist” (I know) named Pat Delgado was wheeled out to look at it, and declared it authentic. When told he’d been had, he essentially quit on the spot and did something more useful with his life, a choice I have a certain amount of respect for.

Anyway, the point is that conspiracies really do happen – the assassinations of Abraham Lincoln, or Archduke Franz Ferdinand, were the results of real, actually existing conspiracies. But they don’t have to be outlandish. They can be really incredibly mundane.

11th September 2001

The first conspiracy theories began to appear online within seven hours of the first plane colliding with the World Trade Centre, when a forum post suggested it had all the characteristics of a planned explosion.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks were the first big moment in the history of conspiracism to happen in the age of the internet. That meant that errors made by official sources or news reports in the hours after the attack – the sorts of errors that are inevitable during fast moving news stories – ended up preserved online forever. To those who wanted to see them as such, these weren’t errors, but evidence.

More than that, the internet provided a platform in which conspiracists could find each other and share theories, and a pseudo-evolutionary mechanism by which the most compelling versions would spread and persist. It’s probably significant that the 9/11 conspiracy theories only really kicked into gear a few years after the attack, as the internet went from being a fringe pastime to a core part of media and life.

Jet fuel doesn’t need to melt steel beams, by the way. It only needs to weaken them. As it turns out, they had already been weakened plenty by the impact of the planes.

***

Before the last date on the list, it’s probably worth pausing to draw out some themes. Conspiracy theories spring from a deeply felt, possibly evolved, need to put a face on natural or social forces. You need a narrative before you can have a counter narrative, and different theories will arise to meet the needs of different times; but it’s broadly true that conspiracism as a whole prospers most at times of insecurity or change.

The internet has made all these things worse. The algorithm pushes more extreme material towards you. Social pressures can lead to radicalisation. And it has made it easier to both unearth new “evidence”, and to find the small community of people who might believe in it.

That final date:

2020

We were all locked indoors for months on end, with only the internet for company. We all felt out of control. And we were told that the reason for this collapse in our hopes and dreams was a slight mutation of a virus living on a bat in a wet market somewhere in central China.

Really, is any of what followed any wonder?

That offer again:

What the hell, you can have Conspiracy instead if you prefer. Just tell me which you want when I ask for your address

.

The fact I sent it out at the exact moment you are trying to work out what to buy someone for Christmas is purely coincidental.

It was actually “OPP”: Ontario Provincial Police.

It’s a Scandinavian symbol of no such thing.